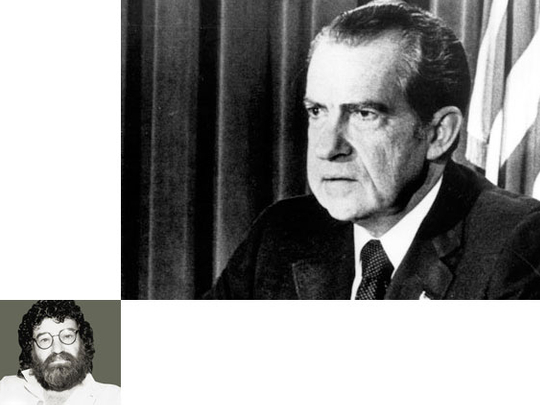

Frequently, the melancholy fate of a disgraced president, especially the president of the most influential nation in the world, is not that he is banished from office, but that his place in history will forever be tarnished. And Richard Nixon, a political leader who had dominated the public stage since the 1950s, cared very much indeed about how he would be judged in the history books.

Exactly 40 years ago today, on June 17, 1972, this self-destructive, though complex, man was done in by a seemingly “third-rate burglary” that his officials in the White House, whose shenanigans he calculatedly abetted, had set in motion.

Now, four decades after the then cub reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward stumbled upon the break-in at the headquarters of the Democratic National Convention and wrote their first stories about it in the Washington Post, exposing the burglary as anything but third rate, we look back in puzzled contempt at the abuse of power evinced by the nation’s chief executive.

The arrest of a team of burglars at 2:30am that day, as they were breaking and entering the Watergate building, was the beginning of damning revelations about Nixon’s resort to sabotage in order to spy on his enemies and to subvert the constitution in pursuit of vengeful political ends.

At the time, the watergate scandal — and “...gate” has entered American semantic lore as a linguistic portal through which all political scandals earn it as a suffix — mesmerised Americans. Two years after his role was unambiguously detailed in the conspiracy, Richard Nixon became the first and only president in the history of the Republic to resign office.

Any number of angles

Now in the cold light of hindsight, we ask, what was it all about and what does it say about America as a polity, a democracy and a culture? We can view Watergate from any number of angles, each to his own. Three here will suffice.

Here’s for starters. We all know that Nixon had chosen his enemies, perceived or imagined, carefully: He could not abide the “liberal elite” in the media, prominent figures in the anti-war movement and sundry Democrats.

By waging a take-no-prisoners war against them, all at once, through wiretapping, intercepting mail, electronic surveillance and “black bag jobs”, or surreptitious entry, he in effect was waging a war against the constitution itself and doing it brazenly.

Consider this image: The president of the United States is sitting behind his desk, in the Oval Office, ordering a “plumbers unit” to break into the clinic of Daniel Ellsberg’s therapist, seeking information that may destroy the reputation and the credibility of the former Rand Corporation researcher who had leaked the Pentagon Papers to the media — in Nixon’s mind an unpardonable act of treason at a time when the war in Vietnam was faltering.

Proud moment

The president’s anti-intellectual rants, not to mention his anti-Semitic mind-set, was evident in one of the White House tapes where he urges one of his top aides, Bob Halderman, to deal with Ellsberg, who just happened to be Jewish American: “You can’t drop it, Bob. You can’t let the Jew steal that stuff and get away with it, you understand? People don’t trust these Eastern establishment people. He’s Harvard. He’s a Jew. You know he’s an arrogant intellectual”.

Watergate was a disgraceful moment in modern American history, but it was also, after the dust had settled and the President resigned in August 1974 (and went on to live for another 20 years) a proud moment. True, the scandal fed into a growing erosion of public confidence and lack of faith in government, widespread to begin with during the turbulent anti-war, anti-establishment movement at the time, but in reality the centre held.

The system worked. It was shown that no one, not even the man holding the highest office in the land, is above the law. The president was made to resign for his improprieties and would surely have gone to jail had his successor, Gerald Ford, not offered him a pardon.

The scandal was cause for new laws leading to changes in campaign financing and a major factor in the passage of amendments to the Freedom of Information Act in 1986.

Though Nixon, on the eve of exiting the White House harped pathetically about how “your president is not a crook”, he went to his grave with his legacy tarnished, his place in history besmirched and his career destroyed.

And here’s the third leg of the tripod on which my view of the scandal rests: Watergate was an edifying juncture in American political culture that ushered in a new, aggressive brand of investigative journalism. The stories written about it have had an enduring impact on the journalistic enterprise, for after Bernstein and Woodward’s book, All the President’s Men, arrived in bookstores, and after Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford starred in the movie adapted from it, generations of young, aspiring hacks enrolled in journalism schools to become investigative reporters.

‘Following the money’

The press will do its job: Hold those in power accountable for their deeds. And reporters will do it the way it should be done — doggedly, by knocking on doors, working the phones, cultivating sources, double-checking facts, looking for patterns in an unfolding story and, yes, as Deep Throat suggested, “following the money”.

If the investigative role that these two living legends played in uncovering Watergate was the meat in the sandwich, then Nixon’s arrogance of power was the bread. The bread today may be stale — we know fully what the crook did in the White House — but the legacy that these two, now ageing reporters left us with, remains to this day as fresh as ever.

Fawaz Turki is a journalist, lecturer and author based in Washington. He is the author of ‘The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile’.