Theresa May, the British Prime Minister, described the United Kingdom and India as ‘natural partners’ ahead of her first trade visit last week. However, Brexit negotiations, economic worries and visa issues have conspired to make her expedition appear doomed from the start.

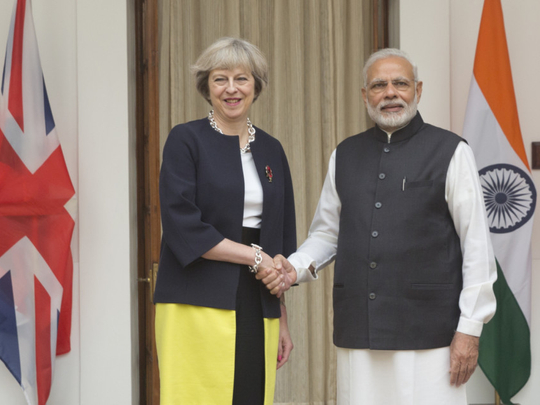

The two countries’ complex relationship has lasted centuries and it is no surprise that May was keen to woo Indian interests as she began the long process of taking the UK out of the European Union. “The UK and India are natural partners — the world’s oldest democracy and the world’s largest democracy — and together I believe we can achieve great things,” May said.

But what exactly could the new Tory leader bring to the table? Just last week, the government — desperate to cut net migration amidst a swelling of nationalist sentiments following the June referendum result — announced changes in visa rules that introduced minimum salaries for high-skilled workers, which could affect the numbers of Indians allowed to work in Britain.

If the UK wants India to be one of its flagship post-Brexit trading partners (the EU has so far failed to cut a deal with the world’s fourth fastest-growing economy), then it has to play ball. Visas for India’s brightest young minds, skilled workers and top businessmen must be facilitated, while students should be allowed to stay in the country once they graduate, no matter how much they earn for the first few years.

May has made concessions by offering a small group of high net-worth individuals and their families access to the Great Club — a bespoke visa and immigration service — to make visa applications smoother. Thousands of Indians on work visas will also be able to join the Registered Travellers Scheme, which will mean they can get through UK border controls more quickly.

But such scraps, combined with the relatively meagre investment deals announced during May’s visit — the official party from the UK was only about 40-strong despite initial expectations that it would be in three figures — will do little to address the alarming decline in the relationship that occurred under her predecessor, former prime minister David Cameron. Study visas issued to Indian nationals fell from 68,238 in the year to 2010 to just 11,864 five years later, despite Cameron’s stated aim of developing a ‘special relationship’ with India.

Britain needs India more than ever, but was it possible for May to offer her hosts the concessions they would rightly expect, while still balancing the anti-immigration effect of Brexit? The two appear incompatible and, with India now holding all the aces in these negotiations, May faces the embarrassment of returning empty-handed.

“Nine out of 10 visa applications from India are already accepted,” May said ahead of the trip, but many locals doubt how much the UK values their business, with entrepreneurs and organisations calling on her to open Britain up to Indians.

Among them, tech body Nasscom called for a high-skilled worker mobility agreement, saying: “A system that restricts the UK’s ability to access talent is also likely to restrict the growth and productivity of the UK economy.” Even Dinesh Patnaik, India’s High Commissioner in London, said: “Students, tourists and short-term visitors are not migrants under any definition. Post-Brexit, you need Indians. Our tourists ... don’t come to Britain due to difficult visa conditions.”

Constitutional crisis

The head of the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (Ficci), A. Didar Singh, also had a warning that UK-India trade faces a “double hit”. “Exports from the UK to India have been declining,” he told the Guardian. “Now, exports from India to the UK will also decline because you’ve lost 18 per cent of your pound’s value. So if I’m sending something to the UK and getting a lower return on it, I’m going to have a think about that.”

While May’s visit may have been a welcome distraction from the constitutional crisis in Britain, its chances of success are limited. India, China and the United States are the key trade deals that Britain needs to secure post-Brexit, so May did the right thing in choosing India as her first trade visit destination, but she needed to come away with firm promises from Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi that India is on board and will head straight to the negotiating table for a free trade agreement once Britain has left the EU.

If May is unable to secure that, Britain will look more isolated than ever and the British premier will have to go ahead and trigger Article 50 early next year in a move that looks increasingly like the country is cutting its nose off to spite its face. With the damage already done to the value of the pound and the increasingly bleak medium and long-term economic forecasts from the Bank of England, Britain’s once-comely features could be permanently disfigured — and all by her own hand.

Martin Downer is a freelance journalist based in the UK.