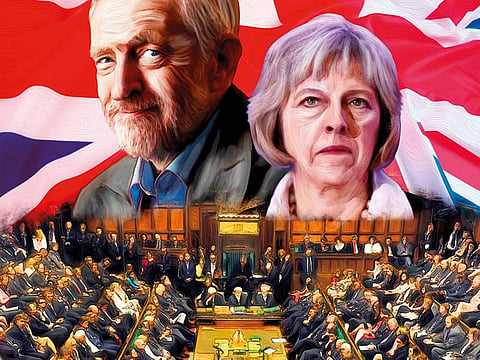

How Corbyn took the wind out of May’s sails

Labour’s game-changing manifesto and youth vote robbed the British prime minister of a landslide

You’ve got to love it. A political system in which there’s no winner. Almost everyone, from some angle, is a loser. Nobody can work out who’ll be Britain’s next prime minister. Everyone’s muttering darkly about another election in October. We’ve come down to wondering whether Sinn Fein will drop its absentee policy. And all any progressive can feel is triumphant, unbridled joy. I mean, you’ve got to love it. Even when you hate it, you’ve got to love it.

What delivered this almighty blow to Theresa May’s magnificently misplaced self-belief? In no particular order — or rather, all these factors are of equal importance.

This was the power of the swarm, people in huge numbers voting in ways that even the bookies told them they never would

n 1) Jeremy Corbyn’s manifesto:

The strategically magical thing about the manifesto was ending tuition fees, which was simultaneously a brilliant, simple, persuasive bid for the self-interested allegiance of a very large and coherent body of voters, and an iteration of his authentically held belief, that tertiary education is a public good.

n 2) Jeremy Corbyn’s campaign:

I read in November — as part of the dazed explanation for United States President Donald Trump’s victory — that “stans” were more important than supporters. I had to Google what a ‘stan’ was: It is a wild enthusiast, an off-the-charts believer, a person who will bore the pub down. Corbyn has these, and no other British politician does. If I’m honest, I read that and I still didn’t believe it, but when our Wales correspondent Steven Morris said last morning: “Corbyn’s crowd was so big in Colwyn Bay that nobody could believe that many people lived in Colwyn Bay,” I thought, “stans”.

n 3) The youth vote:

This is not simply about student fees: It is about Brexit; about pensions as somehow being exempt from the toxic benefits narrative; about the housing crisis; about the dovetailing of so many issues in which the status quo was seen to serve the old; about the radical, the young.

n 4) Voter registration among the young:

From the National Union of Students; from civic tech entrepreneurs, building apps and websites of dazzling innovation; from celebrities too cautious to endorse a party but feeling it enough to push the importance of representation. One million 18 to 34-year-olds have registered to vote since the election was called. It is seismic.

n 5) Turnout helps:

All progressive parties pin a lot of their hopes on the people who traditionally don’t turn up. In the few seats that have declared as I write this, turnout has been much more like referendum levels than 2015 general election levels.

n 6) The Green party:

They have taken a hit in vote share. Numbers in the north-east are down to the hundreds. This is because they took a moral decision to stand aside in some seats, campaign together in others, form non-aggression pacts across constituencies to prevent a Conservative landslide at any cost. The cost, to them as a party, has been pretty great. Typically, it will hit them in university towns, where their vote share was high for reason of a concentration of educated people, thinking about things. In Newcastle-upon-Tyne East, they were down nearly seven points. The very least the Labour Party, and all of Britons, can do is to acknowledge that this was the result of decisive action on their part, and not just an unfortunate loss of interest in the environment.

n 7) That coalition of chaos (or progressive alliance, as we prefer to call it):

While the Greens were the only party to pursue it officially, local activists in huge numbers, from the Liberal Democrats, Labour, the Women’s Equality party, the National Health Action party, worked together to maximise their chances.

n 8) The internet has finally done something useful:

The Conservatives ran their banner ads on Facebook as usual, but this time the progressive wing came back: Crowdpac raised money for candidates and campaigns; networks built up between British progressives and Bernie Sanders’ campaigners, which yielded new activism in the squishy meat world; tactical voting found online organisation that turned it into tactical campaigning.

Psephologists and commentators will spend the next few days talking about technicalities and tactics: How did the Scottish Nationalist Party lose what to whom? Why didn’t the Liberals bounce? When will the Conservatives turn against May? Who will seek allegiance from where, to demand what kind of dominance? But never forget that this was the power of the swarm, people in huge numbers voting in ways that even the bookies told them they never would.

And just as an afterthought: It was the worst Conservative campaign in living memory. And that’s even if you remember Michael Howard.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Zoe Williams is a Guardian columnist.