The constitution The constitution of the Association of Malayalam Movie Artists (Amma, meaning mother), makes it clear that its governing body is the final arbiter in all matters that fall in the organisation’s jurisdiction. The chief of the governing body at present is an actor and a mainstay of the Malayalam movie industry, Mohanlal.

The objectives of the governing body is to resolve “disputes concerning the general welfare of its members with other associations, to extend financial assistance to its members who are disabled, retired or in any other distress”. Gender justice is not specifically part of the scheme; possibly because when Amma was founded in mid 90s, the priorities were financial — especially of those who were out of work.

Historian and culture theorist, Francis Fukuyama, says social change often overtakes economic developments. In real terms one’s financial status may not have substantially improved over a period of time, but the nature of one’s interpersonal relationships, gender equations, fashion and communications, would have undergone massive changes. Amma’s problem is that it is not equipped to meet overnight radical changes in cultural values.

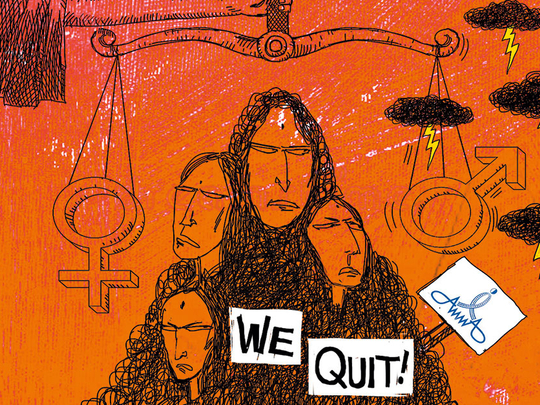

But this is exactly what the four young actresses, Remya Krishnan, Reema Kallungal, Geethu Mohandas, and Bhavana, who have quit Amma in protest are in essence expecting. The trigger for this action is the reinstatement of a Malayalam actor, Dileep, who is out on bail. He was arrested last year and has spent time in jail for serious charges related to an incident involving the alleged abduction and assault of one of the actresses, who is among the four who resigned last week from Amma.

Dileep on bail has all the basic rights of a normal Indian citizen. To be a member of Amma is not a crime. This writer has seen a couple of movies of Dileep, and he is decidedly not a fan of the actor. No matter. About 80 per cent of Dileep’s movies have been major hits. Dileep is a reliable commercial asset to Malayalam film industry. He has been, unlike the great, established stars like Mammootty or Mohanlal, more open to fresh talent in the female roles opposite him. One such was the “survivor”. Around 2015/2016, things soured between the two.

Last week, after resigning as member of Amma, the “survivor” said, Dileep had “blocked her chances” in the industry. Her supporters have bought into this. They may be right. But it is also true that the hero, before he turned villain, was responsible for giving the lady very many solid roles in his movies.

Remya Krishnan, one of the more articulate actors who resigned from Amma, has said there is nothing personal in what she or, for that matter, what her friends have done. The “survivor” was not accorded justice when she was in trouble. But that Amma has been quick to welcome Dileep’s return to the forum.

The fact is Dileep was not formally ever intimated about his ouster, nor was he given a fair hearing at the time. One of his letters to Amma says so. Technically therefore the action to oust him can be legally questioned. In the another letter Dileep says he has no wish to be active in the organisation till his innocence is proved. By seeking to a return to the fold, Dileep is merely exercising his right to be rehabilitated. This is just.

Yet this situation has turned predictably into a binary one. It’s true that the administrative units of the Amma need more women’s representation. But it is equally true that this body was primarily set up to financially help artistes in trouble and facilitate their careers. Amma’s reason for existence is not gender justice. It is justice. In fact, there have been earlier instances of Amma seemingly acting against the interests, and isolating, powerful male actors like the late Thilakan. At that time, the issue — and related themes, such as disparity in wages, discrimination on sets, thwarting one’s career — was not patriarchy, since both victims and perpetrators were patriarchs.

The fact is power has no gender. Consider the recent — and murky — incident in New York of an alleged harassment by the famous New York university humanities professor Avital Ronnel of a male PhD scholar, which has divided the academic community there with leading lights like Slavoj Zizek saying the victim is in the wrong to blame a luminary like Ronnel. An investigation is on. Please note, in passing, that victim blaming is a two-edged sword.

The point is that that barring exceptions, a woman in power is not likely to be greatly different in any given situation than a man because power works down along a certain protocol, a hierarchy of rewards and dispensations, which is what maintains it.

This writer took a random look at the talented and very articulate Remya Krishnan’s Facebook posts. She could be seen going overboard in complimenting the Tamil superstar Vijay — not particularly famous for gender equality — in the context of his upcoming movie, Sarkar (Government). Krishnan’s posts could be seen as genuine admiration for her hero. It could also be a tactic to be on good terms with a potential employer. It is hard to know. But, equally, it would be hard to imagine, anyone flourishing anywhere by voicing critical thoughts of the reigning icons, male or female. The reason why power is hardball play is precisely because the one that has it gets to define its dispensation.

There are many stories involving Dileep’s first wife, Manju Warrier, an actress in her own right, wife from second marriage, Kavya Madhavan, and the “survivor”. The stories allege the “survivor” transmitted information leading to the breakdown of the first marriage. As far as I can see, no one much talks about these as they consider it trivia, and they naturally fear the main discourse on gender justice will be deflected. The Guardian recently carried a critical article on the Amma shenanigans, but refrained from mentioning how an act of petty personal vendetta could acquire, perhaps rightly, the gravity of far-reaching changes.

This writer is not advocating gossip. But he is certainly arguing for seeing things as they are. The Indian media and politicians in general have supported the stand of the young rebels. That itself is cause for concern. In a stiflingly conventional and intellectually dishonest country, if the establishment in one voice is critiquing, say, the chauvinist Amma, the rebels have more to fear the support of friends, than attack from the enemies.

C.P. Surendran is a senior journalist based in India.