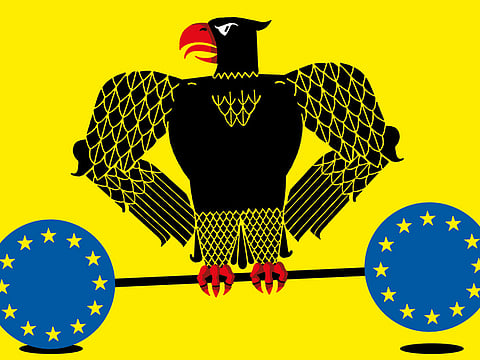

Europe looks at Germany for leadership

Berlin must show the way in protecting the very liberal order that arose in its destructive wake

The victory of Emmanuel Macron in France’s presidential elections — and the defeat of his anti-Nato, anti-European Union (EU), pro-Putin rival Marine Le Pen — is a rare bit of welcome news for those who continue to believe that Europeans and Americans are united by their adherence to liberal democratic values.

Yet, we should not delude ourselves. The Atlantic community still faces a profound crisis of confidence. To survive it, Europe urgently needs strong and enlightened leadership from within. And the best candidate for providing it is Germany.

There is still a real danger the EU will come unglued. While much of Washington might be indifferent to the prospect — with many of America’s conservative friends ready to cheer a day of reckoning for overzealous Brussels bureaucrats — one believes that the end of the EU will be a disaster for the ideals that both Americans and Europeans still hold dear.

Today, according to the European Council on Foreign Relations, there are 45 populist parties vying for influence across Europe. A confluence of factors drives the discontent. Anxiety over terrorism and large-scale migration from Muslim-majority countries are widespread. The south continues to suffer from high unemployment. (Youth unemployment currently runs at 35.2 per cent in Italy, 41.5 per cent in Spain and 45.2 per cent in Greece.) The young democracies of the east are showing an ominous penchant for illiberalism. Brexit has shocked the EU ecosystem. Russian revanchism and deepening state control in Turkey further complicate matters. A Pew poll last year found rising Euroscepticism across the continent. What’s worse, that discontent is especially prominent among the young. One recent survey shows that one out of five EU millennials wants to be out of the Union; nearly half say they’re no longer sure democracy is the best form of government.

Germany’s next national election is set for September. Whether current Chancellor Angela Merkel or her Social Democrat rival Martin Schulz emerges as the victor, it will fall mainly to Germany to find ways to curb Europe’s growing fragmentation and democracy fatigue. Europe’s largest economy has steady growth, with low unemployment (3.9 per cent), and none of the structural impediments holding France back. (France continues to struggle with persistent 10 per cent unemployment and a youth unemployment rate averaging 20 per cent since 1983.)

There’s already talk of new French-German initiatives to revitalise the European project. But Macron’s government will rest uneasily on a coalition of parties from both the Left and the Right who owe him and his newly-created political movement no allegiance. Leadership will have to come from the country that sits at the heart of the continent and that in recent decades has tried to deny or dodge its natural leadership role. The Germans have preferred to seek refuge in a comforting multilateralism that dates back nearly three-quarters of a century. But today, in the age of Brexit and United States President Donald Trump’s “America First” strategy, this sense of discretion is beginning to look more like dangerous complacency.

And yes, greater German leadership should also encompass the ticklish area of defence — despite lingering taboos. Today, German soldiers find themselves on the ground in Lithuania as part of a ramped-up Nato deployment in the Baltic nations. This at least shows Berlin is willing to stand up to Russia, and to stand by its allies in a meaningful way. We need more steps like this.

Creative thinking is also needed on the EU itself. The EU is clearly in deep trouble and any sort of attempt to push ahead with deeper integration is likely to trigger a reaction. Europe’s populist voters seem to share a sense of loss of control. Fairly or not, the EU is identified in many minds with the loss of national sovereignty. Germany is well-positioned to lead an urgently needed rethink on this subject. Any new approach must challenge certain EU articles of faith about integration and the concentration of power in Brussels.

Germans should also seek to end the simplistic derision of today’s populists by elites across Europe. Take Germany’s rabble-rouser, the Alternative for Germany party. It’s a Sammelbecken, a collecting bowl, as Germans say, for xenophobic, anti-Semitic thinking — vile and dangerous stuff. Yet, some voters who support the party have legitimate concerns about excessive migration, EU regulatory overreach (and Greek bailouts) and the widening gap between ordinary citizens and the wealthy and powerful Davos class. Until mainstream German and other European parties begin to deal with mainstream voter grievances seriously, insurgent parties will continue to grow — with space for illiberal forces expanding, too.

And yes, Geert Wilders failed to become Dutch prime minster in the national election in March — but his Party for Freedom ended up as the second-largest party in parliament. Norbert Hofer lost his bid for the Austrian presidency last December, but only after gaining about 46 per cent of the vote. Last Sunday, 10.6 million people in France — one out of three who went to the polls — voted for Le Pen. That’s more than double the support her father got in 2002. And in Germany? The Alternative for Germany will almost certainly enter the Bundestag this autumn. In its short life of four years, the party has already won seats in 12 of Germany’s 16 state legislatures.

Does any of this sound like populism in retreat?

European politics is being remade. On the world stage, Russia, China and Iran are extending their sway. A new tribal world order is threatening to replace the liberal world order upon which our prosperity and security have depended.

In the past, a stable, liberal and America-friendly Europe had been central to American interests. Today, a Germany that brought so much darkness to the continent in the first half of the 20th century must take the lead in protecting the very liberal order that arose in its destructive wake.

— Washington Post

Jeffrey Gedmin, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, is a senior adviser at Blue Star Strategies and a former president and chief executive of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Gary Schmitt is co-director of the Marilyn Ware Center for Security Studies at the American Enterprise Institute. The Washington Post.