Sanctions are finally biting the Qatari economy. Three months into the standoff, there seems to be no breakthrough on the horizon. The economy of Qatar is beginning to feel the strain of the land, sea and air boycott imposed by the anti-terror quartet of Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain and Egypt owing to Doha’s reluctance to stop support for extremism in the region.

Many analysts are of the belief that Qatar will only submit to the demands of the quartet if sanctions start hitting its coffers. So far, the country, according to its officials, has withered the storm and acted in a business-as-usual manner because Qatar is buoyed by its massive $330 billion (Dh1.21 trillion) sovereign wealth fund, overseas assets, strategic finance reserves and gold reserves and other foreign currencies.

All that is very well. Qatar may have a lot of money in reserve, but the problem lies in the fact that if the government starts dipping into its reserves then its slide down the financial slippery-slope is imminent. When will it end and how will it end, given that the political situation continues to be murky in Doha? To make matters worse, Qatar is obstinately sticking to its stance, refusing to accept or address the grievances levelled against it.

It’s a political deadlock but now, and clearly to the detriment of Qatar, it is being mired with economic weaknesses and cracks at the seams. Qatar’s economy — pegged on a sea of gas, dubbed the third richest after Russia and Iran — now reflects a degree of stagnation and sluggishness never experienced since 1995. Forecasts are predicting that its gross domestic product will only grow by 2.1 per cent this year and marginally increase to 3.2 per cent in 2018. However, if the standoff continues and the political situation deteriorates, these figures are likely to slow down to a snail’s pace, and then, very likely, its economy will be characterised as lackadaisical. This is a far cry from the top annual growth rates that Qatar has been experiencing for at least the last 15 years.

ALSO READ:

Personal motives in Qatar mediation denied

Senior Qatari shaikh steps into limelight

Riyadh sets up operation room for Qatari pilgrims and visitors

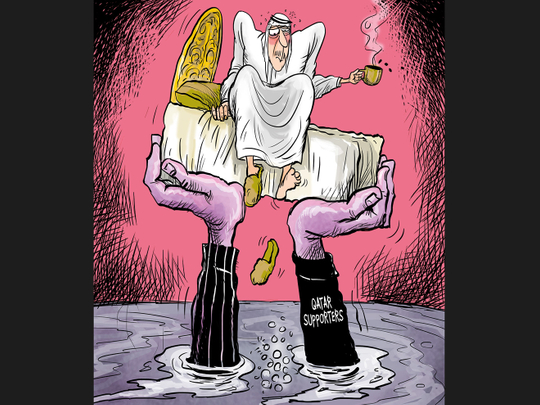

The political leadership in Qatar has to wake up and smell the coffee, as the Americans would say. Since the diplomatic row began on June 5, it had to look at long-distance markets, making its imports much more expensive. While Iran and Turkey quickly moved in to plug what has been cut off through the boycott, these countries are unable to make up for the difference.

Qatar has a population of 2.7 million, most of whom are expatriates. But this is not the real problem. In a bid to build the country and the capital, its infrastructural projects have played an enormous role, requiring mass revenue spending. The problem has been compounded by the fact that Qatar is still in the process of building infrastructure in line with hosting the 2022 football World Cup. It has already forked out $200 billion to host the event, but there is still more to go with at least eight stadiums yet to be constructed, a rail track system to lay and a whole city to build.

In the face of the continuing boycott, these are surely becoming major logistical problems, especially since the material for building these projects are being imported. Other than Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which account for a good portion of its imports, Qatar now has to import from faraway places and not through the usual channels, which means that these imports have suddenly become more expensive. Qatar has got itself into this mess because previously it was dependent on its oil-and-gas revenues. However, with oil prices at historical lows, Doha can no longer rely on these natural resources for its revenue-earning potential.

Investor confidence

Invariably, the Qatari leadership has got itself into a conundrum. The big politics that it always aspired to be a part of (in the regional and international arenas) is slowly screeching to a halt. Invester confidence is slowly faltering despite attempts at constant denial by Qatari economists. While they are being supported by different bodies and experts — internationally and in the West, who say Qatar’s economy is resilient — well-known credit rating agencies such as Moody’s are pointing at risks and dangers with Qatari banks and with the country’s overall economy if its isolation continues. Moody’s, for instance, has downgraded Dolphin Energy, the company that supplies Qatari gas to neighbouring countries. This shows the sensitivity of the issue, regional complementarity as well as the degree of integration within the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Qatar’s obstinacy may affect the other countries in the region because politics and economics are intertwined.

Marwan Asmar is a commentator based in Amman. He has long worked in journalism and has a PhD in Political Science from Leeds University in the UK.