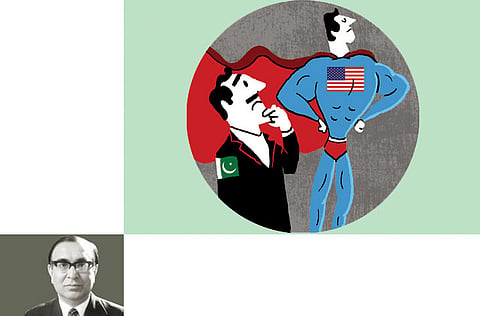

Coping with the sole superpower

Pakistan provides a cautionary tale of the difficulty in dealing with an America reluctant to admit Afghan debacle

Since the turn of the century, a huge swath of the world extending from the Maghreb to Pakistan has contended with the projection of American power. Amongst its major manifestations are deadly wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, destabilisation of Pakistan, marginalisation of Palestinians and unforeseen complexities in the working out of the Arab Spring.

In a memorable piece published in November 2011, the US Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, stated that those in the West who say that the United States could no longer afford to engage with the world have it backward. She, then, went on to spell out the rationale of a massive shift of American military and diplomatic power to the Pacific basin. “Open markets in Asia,” she declared, “provide the US with unprecedented opportunities for investment, trade, and access to cutting-edge technology. Our economic recovery at home will depend on exports and the ability of American firms to tap into the vast and growing consumer base of Asia.” She also underlined the strategic objectives of defending freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, countering the proliferation efforts of North Korea, and transparency in the military activities of the region’s key players. This is clearly a new phase in the containment of Chinese influence in the region and beyond.

Great Powers have historically acted so majestically while on their ascending trajectory. The middle and smaller powers have generally adjusted their postures as best as they could. What is different and what makes this new era of international politics more perilous is that the US is asserting its unrivalled military power when in comprehensive national terms, it is on a downward trajectory; other nations such as China, Russia, Brazil and India are also staking a claim to global influence.

In a remarkable essay published recently in the International Herald Tribune, Charles A. Kupchan pointed out that the rising nations, rather than following the West’s path of development and obediently accepting their place in the liberal international order, are fashioning their own versions of modernity. Interestingly, Kupchan’s short list included the “state capitalism” of the Gulf states. He cautioned American leaders — present and future — against trumpeting a new American Century and against toppling governments in the name of spreading western values.

Pakistan provides an excellent example — in fact, a cautionary tale — of how difficult is the process of dealing with a superpower reluctant to admit that it has lost a decade-long military campaign in neighbouring Afghanistan.

Pakistan had signed on in 2001 without settling terms of engagement. Failure of the Nato-Isaf mission in Afghanistan and its horrific backlash against Pakistan that has all but ripped the country apart made Pakistan’s civil and military leaders to seek some say in the formulation of American strategy in the region, largely to shift a purely militaristic policy to negotiations with all the parties to the conflict. The fundamental American response was to subject Pakistan to increased diplomatic, military and economic pressure to secure its blind compliance with Washington’s policy that had included an Obama-sanctioned surge of troops. The coercive approach to Pakistan ran into a major crisis when a Nato air attack on the Pakistani border post of Salala killed 24 Pakistani soldiers. The pro-western government in Islamabad tried to stem the tide of nationwide anger by closing down Nato’s virtually indispensable overland supply route and by asking parliament to write guidelines to re-set relations with the US.

Pakistan is not the best case from which to generalise about relations between middle level states and Great Powers. But its experience has an indicative value. Parliament produced an initial report that was met with derision from the people — lay as well as informed — and vigorous moves by the American embassy to influence its outcome. It went back to the drawing board and wrote a much better report that upholds national sovereignty, opens the door for an arms-free transit of Nato supplies and tasks the executive with bringing to an end the highly controversial drone attacks on Pakistan. The government got an opportunity to meet an almost undeniable American demand for overland transit; important now and even more when a 100,000 troops are evacuated from Afghanistan with billions of dollars worth of military hardware. In the same breath, however, it faced the daunting task of achieving other goals present in parliament’s resolution in spirit, if not the literal text. These include cessation of drone attacks, end of covert American operations, drastic curtailment of the US footprint in Pakistan, a political settlement in Afghanistan and proactive pursuit of gas pipelines from Iran and Turkmenistan. The Pakistan government has only a limited capacity to pursue these objectives.

From a Chinese or Indian viewpoint, the increasing vulnerabilities of the US in its aggregate national power make for greater space for independent action. For Pakistan that willingly slipped into a tight embrace with Washington, current efforts to regain some freedom of manoeuvring have a touch of pathos. What makes it even poignant is the fact that Pakistan is a considerable nuclear weapons power.

Tanvir Ahmad Khan is a former ambassador and foreign secretary of Pakistan.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox