Mark January 27 in your calendar. All the political parties have done so for it is the point when there will be exactly 100 days to go before the election. This will consume some people with dread, but it gives me a tingle of excitement. Even if the campaign proves to be soporific, the results are going to be worth staying up for.

That is not usually the case. By this stage before most of our elections, we already know who is going to be the next British prime minister. Margaret Thatcher in 1979, Tony Blair in 1997, Harold Macmillan in 1959, and too many other past elections to mention were not really contests. They were coronations. All the sound and fury of the campaign signified little. The people had already settled on who was going to be crowned prime minister some time before they cast their ballots. The last election was a bit different, but not that different. Many expressed themselves surprised when they found we had a hung parliament. They shouldn’t have been. The polls had been indicating that Labour would lose, the Tories would be ahead, and that Prime Minister David Cameron was very likely to be prime minister but without a majority. Which is exactly what happened.

The election of 2015 is one of those extremely rare ones where it is genuinely dicey to make a confident forecast about what will happen. The rise of the insurgent parties has broken the traditional red-blue swingometer. The tightness of the race between the big two, which are currently within a point or two of each other in most polls, makes it extremely hard to say who will have a nose ahead at the finishing post. Which makes past exceptions to the usual coronation rule worth considering when we try to imagine what could happen in May. In relatively recent history, there have been two elections that have upset expectations, two elections when the underdog beat the favourite. One of them was 1992. Labour went into that election with a substantial lead in the opinion polls and a widespread expectation that Neil Kinnock was bound for Downing Street.

Yet when the votes were counted, John Major was back in Number 10 as Tory prime minister. People subsequently said that this was not so surprising after all and attributed the Conservative victory to their ferocious assault on Labour’s economic credibility and the ruthlessly personal targeting of Kinnock by painting him as a candidate not fit to be prime minister. But that post-hoc analysis comes from Professor Harry Hindsight at the Faculty of Wise After the Event. At the time, most people thought Labour was going to win. I remember attending the last Conservative press conference of that campaign. All the big Tory beasts of the time were lined up on the platform. While Major expressed a quiet confidence that he might yet prevail, there was defeat written in the eyes of all of his senior colleagues.

That election has a special relevance today because Cameron was one of the “brat pack” of young Tory apparatchiks working for Major. The current Tory leader cut his campaign teeth then. This has influenced his belief, one shared by George Osborne, chancellor of the Exchequer that they can turn this election into a remake of that one. Their early moves of this campaign have been straight out of the ’92 Tory playbook. Labour, they charge, will wreck the economy with more borrowing and higher taxes – the same “double whammy” they hit Labour with in ’92. Labour leader Ed Miliband, they cry, is not up to being prime minister – exactly the same script the Tories used about Neil Kinnock. When trying to reassure Tory MPs twitchy about defeat, Cameron soothes them with the thought that they were behind Labour in the polls in 1992 only to triumph on election day.

Yet if there are some superficial similarities between now and then, there are also some stark differences. The electorate has changed quite a lot in the two decades since. There was no UK Independence Party (Ukip) around then to eat into the Tories’ right flank. And Cameron is no John Major. The latter had only recently replaced Thatcher and ditched her hated poll tax, creating the impression in the minds of some voters that they had already had a change of government. Major had been prime minister for less than 18 months. By May, Cameron will have been prime minister for five years and Tory leader for nearly 10. With his unassuming manner and modest background, Major could attractively cast himself as the underdog when he went round the country speaking at street corners from a soapbox. The Tories put up campaign posters bearing his face and the slogan: “What does the Conservative party offer a working-class kid from Brixton?” I don’t think it would work quite so well for the Tories if they put up posters with a mugshot of David Cameron and the slogan: “What has the Conservative party ever done for a kid from Eton?”

Cameron does not present himself as the underdog of this contest and no one would take it seriously if he did. Though their poll rating has bumped around the low 30s, the Tories are behaving like they are the top dogs. In interviews and at their campaign events, Cameron and Osborne swagger with confidence that they will still be running the government on May 8. They radiate a belief that they not only expect to win, they are entitled to win.

Of course, Tories are bound to hope that this will be another 1992 when the incumbent came from behind. But what if it turns out that this is a case of an unfancied challenger upsetting expectations? That is what happened in 1970. Harold Wilson had been prime minister for six years. After a lot of economic misery, the skies at last seemed to be brightening. His party, often badly split, had got its act together for the election. A lot of people found the prime minister tricksy and questioned whether he really believed in anything, but he looked assured and presidential in the role. Not so unlike Cameron then.

The challenger to Wilson was widely mocked. Ted Heath struggled to capture the imagination of the country. He had a poor public image. A lot of his party secretly — and not so secretly — reckoned that they were led by a loser. Some similarities with Ed Miliband then. So confident were Buckingham Palace officials that there wouldn’t be a change of prime minister that the Queen planned to spend the day after the election at Ascot. On election night, Heath grabbed some sleep at his flat near the Commons. When he got up, his housekeeper greeted him with news of a transatlantic phone call he had missed: “Mr Nixon rang during the night to congratulate you.” The underdog had won.

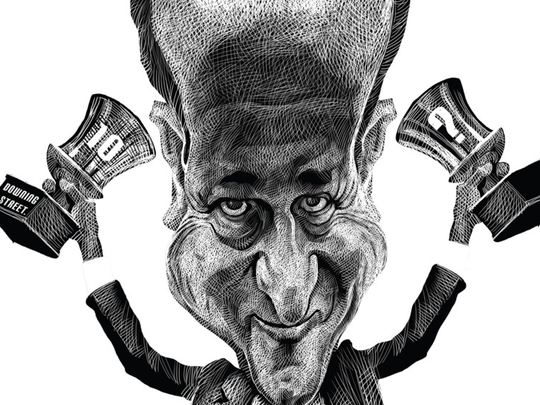

Ed Miliband is, in quite a lot of ways, the underdog of this year’s contest. When he ran for the Labour leadership, very few of his senior colleagues backed him to win, most of them preferring his brother. At various points over the past four and a half years, he has been mercilessly scorned and written off . Even when Labour has had a headline lead in the opinion polls, many people have not really believed it meant anything. Not even senior Labour people. Especially not senior Labour people. Historically, it has always taken Labour more than one election to recover from defeat and its last defeat was its second worst since the First World War. Labour is behind the Tories when voters are asked which party is the more credible on the economy and which party has the best leader. An opposition party has never previously won when it lags on both those questions. The majority of the newspapers are very hostile to the Labour leader. Money is also against him. The Tories will outspend Labour by a ratio of three to one or worse.

Could Miliband turn these handicaps to his advantage? The British are supposed to love an underdog. So there’s a potential campaign narrative available to the Labour leader as the plucky challenger battling against some formidable odds. There’s also a dilemma. On the one hand, Labour wants to present itself as a party of government that is confident of winning. On the other hand, the rise of the minor parties suggests that underdoggery is in fashion. And the way the economy has left people feeling beaten up means there are a lot of voters out there who might have instinctive sympathy with underdogs.

The Labour leader has sometimes embraced the role by casting himself as the challenger to the status quo, taking on the big battalions in the media, finance and business on behalf of the little man. He has occasionally acknowledged that he must “defy history” if Labour is to win. The Tories have not wanted TV debates because they fear that Miliband could flip his poor ratings in the polls to his advantage by beating expectations.

Could this be one of those elections in which, when the votes are counted, the underdog turns out to be the top dog? I can’t tell you for sure. But finding out is another good reason to stay awake on the night of May 7.

—Guardian News & Media Ltd