Senator Lindsey Graham once described John McCain as someone who would “run across the street to get in a good fight.”

McCain’s final battle came straight to him. I’m not talking about the one against brain cancer, which has kept the 81-year-old senator at home in Arizona for months and prompted many friends, including Joe Biden, to travel there recently to see him, possibly for the last time. I’m talking about the one against Donald Trump.

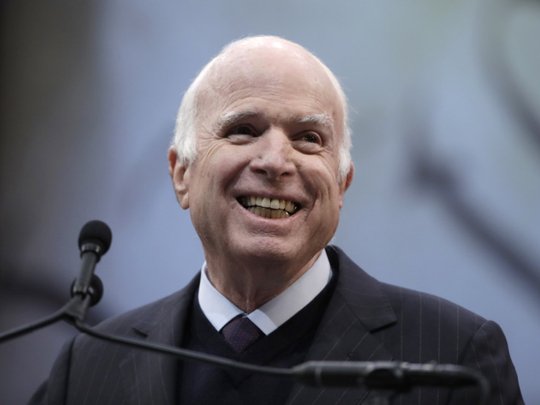

McCain has waged it in public remarks since Trump’s election, including a speech in Philadelphia last October, when he pushed back against the “half-baked, spurious nationalism” that was gripping too many Americans and lamented the abdication of America’s moral leadership in the world.

He wages it in a forthcoming book, The Restless Wave, an advance excerpt of which includes his complaint that Trump fails “to distinguish the actions of our government from the crimes of despotic ones” and that he prioritises “a reality-show facsimile of toughness” over “any of our values.”

The fight isn’t really between two men. It’s between two takes on what matters most in this messy world. I might as well be blunt: It’s between the high road and the gutter. McCain has always believed, to his core, in sacrifice, honour and allegiance to something larger than oneself. Trump believes in Trump, and whatever wreckage he causes in deference to that idol is of no concern. Trump finds McCain’s biography and example threatening; that was obvious in an insult in the summer of 2015, just a month into Trump’s presidential campaign. At a forum in Iowa, Trump mocked McCain’s many years as a prisoner of war in Vietnam — years during which McCain refused offers of release because he didn’t want to be a tool of North Vietnamese propaganda — by saying: “He’s not a war hero. He’s a war hero because he was captured. I like people that weren’t captured.”

McCain brushed it off. “He never mentioned it,” General David Petraeus, who sits on the board of the McCain Institute for International Leadership at Arizona State University, told me. It’s all too easy, in the context of Trump, to idealise political leaders who came before him and airbrush their flaws. McCain has his share, including the occasional rashness reflected in his selection of Sarah Palin as a running mate in 2008. Did she help pave the way for Trump? What a cruel irony if so.

Trump cited bone spurs in his heels to avoid Vietnam. McCain, a Navy pilot, had an arm broken and ribs cracked during the torture that he endured while imprisoned by the North Vietnamese.

Trump jump-started his political career with the fib that Barack Obama was born outside the United States and thus an illegitimate president. During the last weeks of Trump’s presidential campaign, he branded Hillary Clinton a criminal and encouraged supporters to chant, “Lock her up.”

During the last weeks of McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign, he grew so concerned about supporters’ hostility to and misconceptions about Obama that he corrected and essentially chided them. “He is a decent person,” he told a man who had volunteered that he was “scared” of an Obama presidency.

Trump demands instant gratification. McCain served for four years in the House before his three decades in the Senate, during which he worked his way up to his cherished post as chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. He tried — and failed — to get the Republican presidential nomination in 2000 before succeeding eight years later. In his new book McCain calls out Trump by name, saying that the president’s lack of empathy for refugees is “appalling.” “The world expects us to be concerned with the condition of humanity,” McCain writes. “We should be proud of that reputation. I’m not sure the president understands that.”

Donald Critchlow, a professor of political science at Arizona State University, notes: “If Trump’s presidency fails, Senator McCain will be remembered as a Jeremiah who warned that the party had taken a road to perdition.” And if it succeeds? Then he is “part of an old guard” vainly resisting a new day, Critchlow said.

Either way he has my gratitude. Although I disagree with many of his political views, including his too-keen itch for foreign intervention, that doesn’t prevent me from admiring him enormously. Nor should it, a point that he makes in his book.

“I don’t remember another time in my life when so many Americans considered someone’s partisan affiliation a test of whether that person was entitled to their respect,” he writes, ruefully, adding that while Biden, Ted Kennedy and other Democratics never voted for the same candidate for president as he did, his friendships with them “made my life richer, and made me a better senator and a better person.”

Such grace is unimaginable from the current US president. That’s why it’s so vital that McCain is using his waning time to model it.

— New York Times News Service

Frank Bruni is a senior columnist and author of best-sellers like Born Round and Ambling into History.