It took eight months, but the US has finally apologised for killing 24 Pakistani soldiers in a firefight on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. With that, the US military is again able to use routes through Pakistan to supply its forces in Afghanistan without paying exorbitant fees. Plus the threat that Pakistan will bar US drone strikes is for now moot.

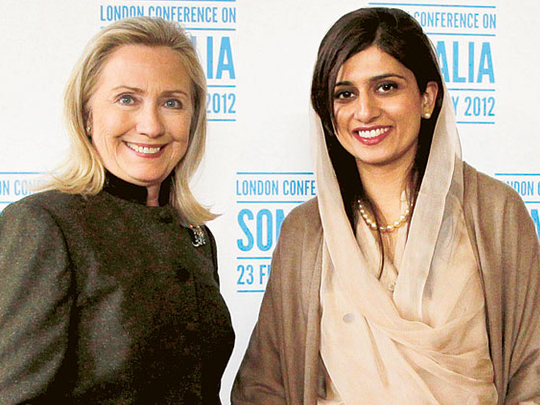

However, the main implication of the apology, a triumph of Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, over both the White House and the Pentagon, is that it ends the experiment of the US trying to bully Pakistan into submission.

The clash in November between US and Pakistani forces was a mess, with miscommunication on both sides, but fatalities on only one. Pakistan, still seething over the US breach of its sovereignty in the raid on Osama Bin Laden’s compound, closed US military supply routes to Afghanistan when the US initially refused to apologise. The US, in turn, froze $700 million (Dh2.57 billion) in military assistance and shut down all engagement on economic and development issues.

In a further deterioration of ties, the Pakistani parliament voted to ban all US drone attacks from or on Pakistani territory. The Pakistanis held firm in their insistence on an apology. Officials at the Pentagon thought the case did not merit one. Many had no sympathy for the Pakistanis, whom they regarded as double-dealers for stoking the insurgency in Afghanistan and providing a haven to the notorious extremists of the Haqqani Network.

The White House feared that an apology would invite Republican criticism. Throughout the crisis, Clinton and her senior staff argued that the US should apologise. She supported re-engaging with Pakistan to protect a critical relationship while also holding Pakistan accountable for fighting the Taliban and other extremists, a point she has raised in each of her conversations with Pakistani leaders. Clinton’s recommendations were contrary to the policy the Pentagon and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) put in place in early 2011.

Relations had soured when the Pakistani authorities held CIA operative Raymond Davis after he had shot two Pakistanis. Frustrated with Pakistan’s foot-dragging on counterterrorism, the two agencies successfully lobbied for a strategy to reduce high-level contacts with Pakistan, shame Pakistan in the media and threaten more military and intelligence operations on Pakistani soil, like the killing of Bin Laden. It was a policy of direct confrontation on all fronts, aimed at bending Pakistan’s will. It failed. Pakistan stood its ground. Far from changing course, Pakistan reduced cooperation with the US and began to apply its own pressure by threatening to end the drone programme, one of the Barack Obama administration’s proudest achievements. Months of behind-the-scenes wrangling failed to resolve the apology issue. A high-level US visit to Islamabad on the eve of the May 20-21 Nato Summit in Chicago proved a fiasco. Pakistan informed the Americans that after an apology, it would charge a much higher fee to let Nato supplies into Afghanistan. (That has not come to pass, though.)

President Obama refused to meet Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari at the summit unless the supply routes reopened, but that did not break the impasse. Finally, Washington tallied the costs of confrontation with Pakistan. Supplying troops through other routes was costing an additional $100 million a month.

Without Pakistani roads, the US military would not be able to get its heavy equipment out of Afghanistan on time or on budget once it begins to withdraw from the country in earnest. If Pakistan remained off-limits, the US would have to rethink its entire exit strategy from Afghanistan. What’s more, if Pakistan truly shut down the drone programme, it would cripple the administration’s most successful terrorism-fighting tool. Pakistan might also close its airspace to US planes flying between the Arabian Gulf and Afghanistan.

Americans were understandably angry that Bin Laden was found hiding in a Pakistani city, but few knew that the plane that transported his body from an Afghan base to a US Navy ship for a sea burial had to fly over Pakistani territory.

The conclusion: Open conflict with Pakistan was not an option. It was time to roll back the pressure. The apology is just a first step in repairing ties deeply bruised by the past year’s confrontations. The US should adopt a long-term strategy that would balance US security requirements with Pakistan’s development needs. Managing relations with Pakistan requires a deft policy — neither the blind coddling of the George W. Bush era nor the blunt pressure of the past year, but a careful balance between pressure and positive engagement. This was Clinton’s strategy from 2009 to 2011, when US security demands were paired with a strategic dialogue that Pakistan coveted. That is still the best strategy for dealing with this prickly ally.

— Washington Post

Vali Nasr is dean of the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University and a senior fellow in foreign policy at the Brookings Institution.