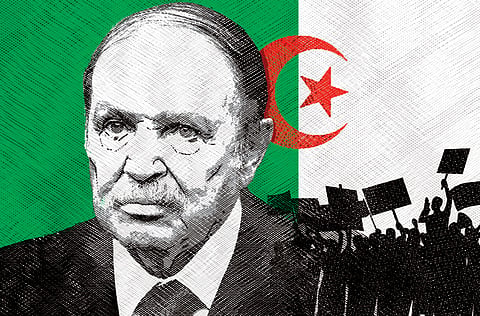

Algeria’s frail and silent president

Presidential elections hold no promise of democracy for Algerians

A frail pensioner in a wheelchair casting a vote was billed as a triumph for Algeria on Thursday. Those of us who watched Abdul Aziz Bouteflika being pushed towards a temporary polling station at a school in the Al Biar district of Algiers certainly felt a sense of occasion. The 77-year-old president is part and parcel of his country’s history and with the sun shining and the views stretching out towards the white-washed kasbah and the Mediterranean beyond, he was cheered by enthusiastic well-wishers.

The problem as far as democracy is concerned is that the smiling statesman in his leather-bound executive invalid chair is set to remain president for another five years. This will bring his term to two decades, which sits uncomfortably with Algeria’s claim to be an exception to the unjust rule that sparked Arab Spring revolutions in Libya, Tunisia and Egypt three years ago.

Bouteflika is by no means a Muammar Gaddafi, Zine Al Abidine Bin Ali or Hosni Mubarak, but his decision to stand in what were described by his government as fair and free elections was unwise. He won an unlikely 90.24 per cent of the vote when he last stood for re-election, in 2009, and his opponents are still making accusations about vote rigging. Bouteflika’s main rival today was the former prime minister Ali Benflis, who won just 6 per cent of the vote five years ago. Little wonder that many Benflis supporters called for a boycott this time around and an abstention rate of up to 80 per cent was forecast.

Bouteflika’s record of national service is unquestionable but he has always placed security above democratic and economic progress. He is a veteran of the National Liberation Army, which defeated France the former colonial master in 1962. Bouteflika became president in 1999, when a civil war in which up to a quarter of a million people died was coming to an end. He was credited with bringing about national reconciliation and stability. Together with his feared military and intelligence officers, he has continued to battle Islamic insurgents committed to destroying his socialist-style security state.

Against such a background of violence, the appetite for street demonstrations, let alone revolutions, is limited in Algeria. As Nasser, a 23-year-old unemployed mechanic, told me: “Running around shouting about how much you want change is not a wise thing to do here in Algiers. We know that people in other countries can choose their leaders and have far better lives. That is all we are asking for.”

The majority of those living in a country in which about 70 per cent of the population is under 30 certainly want to see its enormous economic potential exploited to solve endemic social problems, including spiralling unemployment and a housing crisis. Algeria is a leading Opec producer and the third-largest supplier of natural gas to the European Union. Foreign reserves from energy sales total $200 billion (Dh735.6 billion), but wealth is not distributed evenly.

Algeria is also of huge strategic importance, with British Prime Minister David Cameron, along with the Americans and French, viewing the country as a key ally in the war against terror. In a notoriously unstable area, Bouteflika is at least a predictable player with whom the West can work.

There have been outbreaks of organised dissent across Algiers in the past few days and these will certainly continue after election day, which many banners described as “April 17: Day of national mourning”. Protesters believe the ruling party fulfilled its historic role during the war of liberation and the bitter post-colonial period and that it is time for proper democratic rule.

All the indications are that even Bouteflika agrees: Government sources in Algiers suggested this week that he is “ready for change”, but that key lieutenants wanted him to remain as a figurehead. Perhaps the most noticeable aspect of the behaviour of the small, dapper senior citizen who was wheeled to the ballot box was that he remained implacably silent. It was the abiding image of Algeria’s presidential election day and summed up the state of its democracy.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Nabila Ramdani is a Paris-born freelance journalist and academic of Algerian descent.