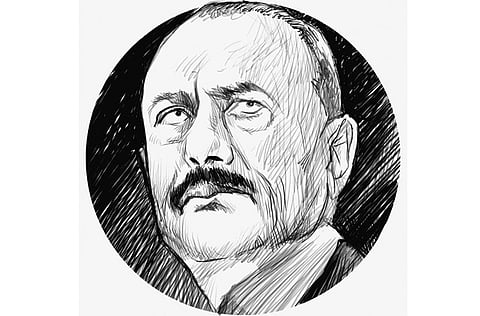

Yemenis turn the page on Saleh

Despite what acolytes claim, they perceive the president for what he is — an expert manipulator who craves power

Unlike Syrian President Bashar Al Assad, who prematurely claimed that Syria would be bypassed by the current Arab uprisings, Yemen's President Ali Abdullah Saleh knew his end was near and is now negotiating an orderly departure. Like other paragons of absolute authority whose very survival depends on how well they seduce gullible masses, Saleh is entertaining ‘proposals' to ease him out of power.

One of the latest was made by the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Secretary-General Abdul Latif Al Zayani, who recently met with Saleh in Sana'a to deliver a package deal. Reportedly, the arrangement consisted of what came to be known as the ‘30-60 Plan', which offered the dejected president and his family immunity from prosecution if he left within a month. Does the Yemeni have that much time?

Saleh, who hails from the Al Ahmar tribe within the Hashid confederacy, joined the military in 1958 after completing his elementary education. Over the years, he rose through the ranks of what was then the Yemen Arab Republic, also known as North Yemen.

In 1977, the President of North Yemen, Ahmad Bin Hussain Al Gashemi, appointed him military governor of Taiz. When Al Gashemi was assassinated, Saleh, who was then a colonel, manoeuvred three potential rivals in the four-man provisional presidency council. Though few recall how he managed to do it, Saleh ran for parliament in 1978, got elected, and was quickly propelled to the presidency of the republic. Ruling a truncated society, Saleh tamed his population and, in the process, exasperated tensions with the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY or South Yemen). Consequently, the two Yemens engaged in sporadic military clashes that escalated into open conflict by 1979.

Paradoxically, as Saleh was gradually losing the war, he survived a coup attempt. Still, the PDRY lost its chief sponsor after the Soviet Union collapsed, which led the autocrat in Aden, Ali Salim Al Beidh, to accept unification in 1990 with Saleh as president of the nascent Republic of Yemen.

Political genius

A gambler who frequently bet on regional losers, Saleh's political genius at home was evident after he manipulated various constituents to triumph within the General People's Congress. For all his prowess, however, it was unclear which major military victories prompted him to seek, and receive from parliament in 1997, a promotion to the rank of field marshal.

In the event, the first directly elected president in the country's history, Saleh apparently won over 96 per cent of the vote in 1999. This was standard operating procedure for dictators even if few could match Saddam Hussain's 100 per cent mark in 2002, when 11,445,638 eligible Iraqi voters cast their votes in unison for the Iraqi strongman. In September 2006, Saleh was re-elected to a seven-year term with a mere 77 per cent of the vote, while Faisal Bin Shamlan gathered 22 per cent.

Unlike Saddam, however, Saleh is interested in leaving office if a sweet deal can be cut. A few weeks ago, the Yemeni leader promised to step down in 2013 without passing the torch to his son Ahmad, who serves as the Commander of the Republican Guard.

He even offered to amend the constitution to give more powers to parliament. "We will continue to resist," he declared "undaunted and committed to constitutional legitimacy, while rejecting plots and coups," adding that "those who want the chair of power have to get it through ballot boxes."

This remarkable adoption of constitutionalism notwithstanding, several of Saleh's allies, including his half-brother Major General Ali Mohsin Al Ahmar, the commander of the Northwest Military Area, joined protesters. Many are frustrated by the country's rampant corruption in what is one of the poorest countries in the world.

Regrettably, Saleh does not seem to understand that he is no longer a prized asset, even if his primary tactic during the past few weeks was to market his alleged skills to deny Al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) a foothold in the country. Yet, with less than 300 members in Yemen, AQAP is not more than a threat to itself. What the president does not get is that Yemenis have, by and large, turned his page after three long and largely ineffective decades in office.

As if these years were not painful enough, his shameful negotiations to orchestrate a departure, while seeking immunity for countless family members along the way, perfectly illustrated an ‘Ali Baba and his 40 Thieves' mentality.

In the course of an hour-long interview a few years ago, the Yemeni head of state brazenly told me that I knew nothing of the Arab world, but needed to learn how things worked here. To my polite but firm questions on his ties with various Saudi officials, Saleh shouted, wishing to intimidate.

Needless to say that among rulers who granted me audiences over the years, Saleh stood out as a true brute, which confirmed the notion that a man who disrespects a guest cannot possibly be kind to his own.

Beyond acolytes who benefited from his largesse, Yemenis today perceive Saleh for what he is, an expert manipulator who craves power. Decent Yemenis no longer wish to be ruled by an official who makes the army of thieves in Ali Baba's legendary story look good.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is a commentator and author of several books on Gulf affairs.