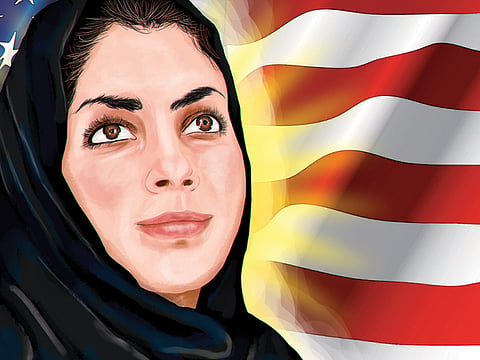

Why Muslims could actually thrive in Trump’s America

Any injustice is an invitation from God to renew one’s faith and find empowerment by correcting it

While hatred for and visceral fear of Muslims began long before Donald Trump’s campaign hatched, his odious rhetoric and reckless decisions promise a potentially horrifying climax.

Given Trump’s intentions for a “Muslim ban” and the fury his followers harbour for Islam, the backdrop for Islam in America right now consists of white nationalist fliers on college campuses, grisly hate crimes, tenuous civil liberties and profound suspicion. Friends and family fear that anything appearing remotely “Muslimy” will provoke malice. There are also concerns that the “clash of civilisations” sought by Trump’s advisers will embolden groups like Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), which seek those disaffected by the West as recruits.

Trump’s presidency has become a moment of reckoning for the country’s 3.3 million Muslims as their faith finds itself embattled, besieged by uncertainty and under duress. Muslims face a temptation to embrace victimhood and retreat, but also a solace, as Islam has been in a similar place before.

In the dusty pages of old Sunday school books are the stories of early Muslim communities that thrived when their faith was beset with challenges. Propelled forward by the universal themes of justice, equality and solidarity that form the Quran’s bedrock, their enlightened struggle resonates under Trump’s presidency.

Born in 610, Islam’s call for social and economic reform became a radical response to the growing inequities in the city of Makkah. Long-honoured tribal ideals had perished as wealth became disproportionately concentrated in the hands of a few oligarchs who controlled the city and all of its political, religious and economic affairs. Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) sought to change this entrenched social order with Islam’s unprecedented message of equality, which embraced Makkah’s indigent and marginalised.

Those who chose to convert to Islam in its nascent stages voluntarily chose to oppose this status quo despite the great personal cost. Many sacrificed their lives, abandoned lives of privilege, severed bonds with family members, endured persecution and ignored ridicule because they were called to a purpose far greater than themselves.

The primacy of justice in Islam is captured eloquently in this verse from the Quran: ‘O ye who believe! Stand out firmly for justice, as witnesses to Allah, even as against yourselves, or your parents, or your kin, and whether it be (against) rich or poor: For Allah can best protect both. Follow not the lusts (of your hearts), lest ye swerve, and if ye distort (justice) or decline to do justice, verily Allah is well-acquainted with all that ye do.”

In God’s eyes, justice is never a matter of choice, but the only choice. The pursuit of justice then becomes a means of showing devotion and demonstrating commitment to God, a duty.

In his letter from Makkah in 1964, Malcolm X wrote of how Islam’s belief in the oneness of God had bred equality within the religion’s adherents. After years of being hardened by America’s racism, oppression and exploitation, he was heartened to see a world in which justice was manifest as love and brotherhood: “During the past 11 days here in the Muslim world, I have eaten from the same plate, drunk from the same glass, and slept on the same rug — while praying to the same God — with fellow Muslims, whose eyes were the bluest of blue, whose hair was the blondest of blond, and whose skin was the whitest of white. And in the words and in the deeds of the white Muslims, I felt the same sincerity that I felt among the black African Muslims of Nigeria, Sudan and Ghana. We were truly all the same (brothers) — because their belief in one God had removed the white from their minds, the white from their behaviour, and the white from their attitude.”

There are echoes of a faith synonymous with justice in the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail, where he wrote of a church that acted not as a thermometer to merely gauge the prevailing social issues of the time, but as a thermostat that could influence society’s bend towards justice. Similarly, when Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel returned from Selma after a march during the Civil Rights era, he was asked whether he found much time to pray. He responded, “I prayed with my feet.”

It is this same spirit that animated 20 rabbis who were arrested while demonstrating against the “Muslim ban” in front of the Trump Tower in Manhattan and that inspired evangelical Christian leaders to condemn Trump’s executive order for giving preference to Christian refugees over Muslim ones.

While Trump poses challenges for Muslims, his presidency also presents opportunity as we adopt the struggles of our neighbours and marry them to our individual struggles. Every instance of police brutality, an arrival of an Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent at a door, swastika graffiti, contraction of rights or silencing of a woman extends the opportunity to strengthen our faith and forge new alliances. As American poet Emma Lazarus wrote, ‘Until we are all free, we are none of us free’.

Any injustice is an invitation from God to renew one’s faith and find empowerment by correcting it. Every street and every airport becomes sacred ground as each protest serves as an act of worship, each march as a prayer and each moment of dissent as a pilgrimage. Resistance will thus become an act of faith.

This moment provides a call to live the ideals of a faith that has sustained so many for centuries and allowed them to find God daily through their desire to create a more just community for all.

Actually, there is perhaps no better time to be a Muslim in America than now.

— Washington Post

Jalal Baig is an oncologist and a writer in Chicago.