War against terror far from over

Abdel Bari Atwan writes: There is a danger that Al Qaida may emerge more radical and united under the banner of Bin Laden's 'martyrdom'

In an interview with Al Quds Al Arabi in 2004, Osama Bin Laden's former bodyguard, Abu Jandal, described how the Al Qaida leader had given him a pistol loaded with two bullets, and ordered that he kill him in the event of his being surrounded by "the enemy".

The western media is apparently taking care to avoid giving the impression that Bin Laden died courageously; yet martyrdom is what the Al Qaida leader desired more than anything — he told me as much when I interviewed him in 1996 — and rumours that he died from two bullet wounds to the head suggest that a chosen bodyguard was obliged to fulfil that final duty.

The circumstances of Bin Laden's assassination by US special forces beg serious questions about the integrity of US and Pakistani intelligence services. Not least how it was that he lived in the heart of Abottabad, a small Pakistani city, apparently untroubled by local intelligence services or citizens eager to claim the $25 million (Dh91.75 million) bounty on his head.

While the US was scouring the mountainous border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, Bin Laden managed to build himself a safe-haven less than a kilometre from Pakistan's most important military academy.

It seems he received high-profile visitors here, too, not least the infamous leader of Al Qaida in Indonesia, Umar Patek, who was himself arrested in Abottabad in January this year.

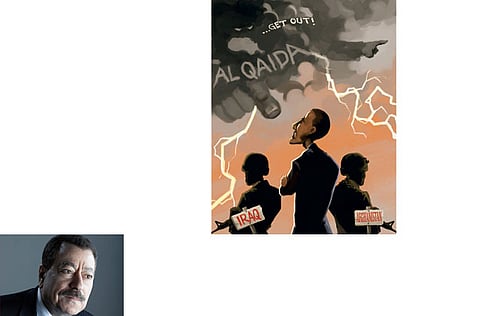

Obama's prospects

US President Barack Obama made killing or capturing Bin Laden his main security objective, and his chances of re-election in 2012 are greatly enhanced by this operational success — even though it has taken more than ten years, two long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the lives of more than a million Iraqi, Afghani and Pakistani civilians, and over a trillion US dollars.

The question now must be, does the demise of the Al Qaida leader mean the end of the organisation itself? It seems likely that the answer is no. In fact the assassination may have the opposite effect.

There is a greatly increased risk of attacks on US and western targets in retribution for Bin Laden's death. If his dead body was indeed ‘buried at sea' as the White House claims, this is not only unacceptable in Islamic terms, it is deeply disrespectful which may further inflame supporters already inclined towards vengeance.

By way of an aside — given that the US was eager to parade the corpses of Saddam Hussain's sons Uday and Qusay, it is curious that this greater opportunity to display this even greater prize has been passed over. Conspiracy theories abound — particularly given that no authenticated photographs of Bin Laden's body have been produced by the US.

Al Qaida central's most active off-shoots at present are in Yemen, Somalia and the Maghreb. At the end of April, an Al Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) suicide bomber killed 15 in a Marrakesh cafe and the chaotic situation in Libya also presents opportunities for the group. With its access to the Mediterranean coastline, a vengeful AQIM might present a real threat to mainland Europe.

Al Qaida has been around for more than 20 years, and in that time its organisational structure has evolved in such a way that Bin Laden's demise may not greatly affect its future. The pyramid power structure initially employed has been replaced by a network of enfranchised or otherwise affiliated groups each with their own ‘emirs'.

Roles and power are widely delegated, so that if one leader is killed or captured it will have a minimum impact on the group's survival and ability to continue with their agenda undeterred. Ironically, the benefits of this structure were suggested to the mujahideen by US military advisers during their decade-long fight against the Soviets (1979-1989).

Al Zawahiri — who will now take command of ‘Al Qaida central' — is, if anything, more militant than Bin Laden and is the suspected operational mastermind behind 9/11, and the bombings in Madrid and London. Furthermore there is a new generation of leaders, some of whom have spent most of their lives as fugitives and jihadists.

Generation Next

These include Bin Laden's son, Sa'ad; the high profile English-speaking cleric Anwar Al Awlaki now based in Yemen and believed to be behind at least two foiled attacks on US targets; and Adam Gadahn, ‘Al Amriki' (the American), who fronts many of the organisation's increasingly sophisticated videos and hails from Oregon in the US.

It is this generation which has ensured Al Qaida's continued and expanding presence on the internet, its success in so-called ‘cyber-jihad', a growing ability to communicate in a wide variety of languages, and the establishment of a powerful independent media base which includes their own film production units and a number of glossy magazines.

The new generation of Al Qaida has also developed an increasingly sophisticated intelligence network which has enabled it to mount attacks on CIA targets in Afghanistan for example.

To return to our interview with Jandal in 2004 — the former bodyguard explained why Bin Laden could never accept being caught alive: "he wanted to become a martyr, not a captive, so that his blood would become a beacon that arouses the zeal and determination of his followers".

There is indeed a danger that post-Bin Laden, Al Qaida may emerge even more radical and more closely united under the banner of an iconic martyr.

Finally, Al Qaida's ‘popularity' was founded largely in the US invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan since it gave voice to a widespread sense of outrage among Muslims. To ensure Al Qaida's decline Obama should withdraw all US troops from both countries as soon as possible.

Abdel Bari Atwan is editor of the pan-Arab newspaper Al Quds Al Arabi.