US needs to show leadership role in South China Sea

A coherent Washington policy towards its allies will reassure them and send a message to Beijing that its belligerence will have consequences

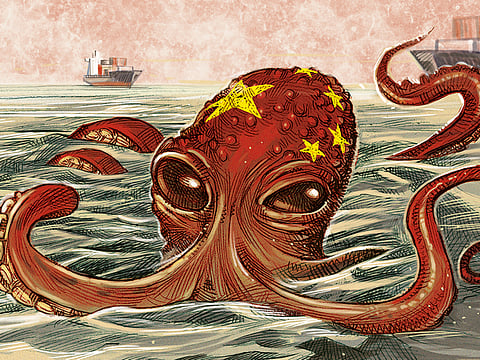

If anything, the recent Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore highlighted the mounting perils in the South China Sea, which some security experts describe as the “battleground of the future”, where the smaller states in the region — particularly those with claims to the gas and oil-rich islands — fear losing their rights and sovereignty as China does some muscle-flexing with its superior naval and air power.

The United States, which also has a presence in the Pacific, can easily get drawn into the conflict.

China has often used “historic reasons” to assert its claims and sovereignty over the islands, while the US argues that freedom of navigation in international waters is the right of all states and uses it to oppose Chinese domination of the South China Sea. The US wants a “rules-based order” in the Indian and Pacific oceans.

China asserts ownership and control over more than 80 per cent of the South China Sea, a $5 trillion (Dh18.39 trillion)-a-year shipping route where five others — Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam — have territorial claims.

The US has, meanwhile, changed the moniker of its Pacific command to “Indo-Pacific”, obviously, to get India involved in a region that is seen as its sphere of influence, with American politicians, including James Mattis, the Defence Secretary, alluding to India’s naval power and its claims to the Indian Ocean domain.

But US President Donald Trump’s ‘yes-no-yes’ kind of responses — that too as tweets — on world issues, including his recent meeting with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, have raised doubts about US reliability among allies who feel that the incoherent responses were sending the wrong message of disunity and disharmony in the US-led alliance to China, which could be emboldened to embark on a misadventure.

Mattis — who more or less stuck in Singapore to the script, followed by his Democratic predecessor Ash Carter on the freedom of navigation operation and the international community’s opposition to Chinese territorial claims — called for unity among allies, particularly with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), whose members feel their claims are being overridden by China’s fait accompli claims.

Mattis felt that China’s aggressive posturing could lead to its international isolation, forcing it to reconsider its actions. The US excluded China from this year’s multilateral Rimpac naval exercises — a “small penalty” for China to pay, according to Mattis — while the Chinese were dismissive of the Indo-Pacific strategy, giving it no chance of lasting for long.

Meanwhile, US actions are also alienating it from its allies. Indeed, security experts are alarmed at the recent political melee between the US and its allies over the imposition of tariffs and, before that, the US pullout from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) that aimed at strengthening the US ‘pivot to Asia’ and galvanising the TPP countries into one gigantic US-led trading bloc.

The Southeast Asian attitude is hardening towards China. Fears of Chinese hegemony in South China Sea are accompanied by rising scepticism against China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its utility to the participating nations. There is anxiety among BRI participant states that the “investments” promised are, in fact, loans making the weaker states perennially indebted and subservient to China.

The Philippines President, Rodrigo Duterte, on assuming presidency, squandered The Hague Tribunal’s ruling favouring the Philippines in the dispute over its claim to islands in the South China Sea and, instead, reached a modus vivendi with China in exchange for some economic sops from the latter. Though Duterte recently criticised China over a fishery dispute, his future attitude towards Beijing will very likely depend on the Trump administration’s success in dispelling the fears of its allies over Washington’s long-term commitment to the region’s security.

US House Republican Mac Thornberry, who also attended the Shangri-La conference, said that during a visit to the Philippines, he had found people there extremely concerned about China, though cautious about speaking out.

Many strategists feel that a naval alliance in the region could deter Chinese expansionism. The formation of the Quad, comprising four major military powers — the US, Australia, India and Japan — is a step in that direction, but it remains to be seen to what extent India will go in joining a formal alliance that is anathema to some Indian thinkers who are still sentimental about non-alignment.

During a discussion in Singapore, Zhao Xiaozhuo, a senior colonel and deputy director of the Centre on China-US Defence Relations in the PLA’s Academy of Military Science, said that sending warships into Chinese territorial waters violated the country’s law, and warned that if China’s islands and reefs were continuously threatened by activities under freedom of navigation, China would eventually station troops on such reefs.

Mattis rejected Zhao’s claim that freedom of navigation operations in international waters was tantamount to militarisation, reminding that a 2015 international tribunal decision had endorsed this view, which China had ignored.

Mattis’ argument about safeguarding free navigation would gain greater support if there was a coherent, consistent and predictable US policy towards its allies who need reassurance that America has not abandoned them and that it will continue playing the leadership role. Articulating this resolve will not only put the minds of allies at ease, but also send a clear message to China that it would face security and economic consequences, if it continued with its belligerent behaviour.

Manik Mehta is a New York-based journalist with extensive writing experience on foreign affairs, diplomacy global economics and international trade.