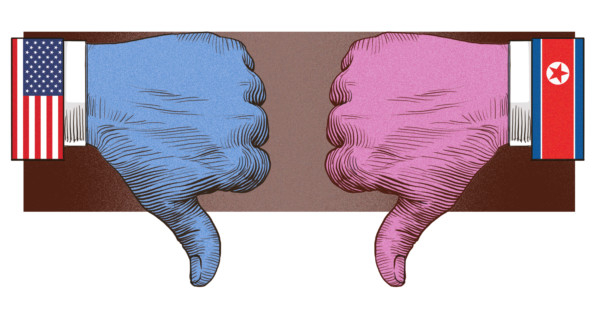

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un concluded at the weekend a multi-day tour of Vietnam after the collapse on Thursday of his summit with US President Donald Trump. The clear differences between the two sides, over the scope and pace of denuclearisation and sanctions rollback, means there is growing uncertainty whether the talks process will now collapse or continue.

To be sure, there are historical precedents for such high-profile negotiations to break down, and then recover, including the US-Soviet negotiations between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev in 1986 and 1987. However, it appears the gaps between Trump and Kim remain wide, and the North Koreans have claimed that they will not change their position, and also disputed Trump’s account that the reason the talks collapsed was that Pyongyang asked for full sanctions rollback.

One of the reasons why Pyongyang may not move far or fast on its positions is that, to date at least, it is Kim — rather than Trump — who has emerged as the bigger winner from the engagement process. So far Kim has made few concrete concessions to the United States with Trump touting last week as evidence of his diplomatic success with Pyongyang the recent absence of missile and nuclear testing.Ramachandra Babu/©Gulf News

At the same time, the US president has called off joint military exercises between US and South Korean forces; exchanged effusive letters of praise with Kim; held out the prospect of an easing of sanctions on Pyongyang if it does “something meaningful” on denuclearisation; said that he is in no rush to conclude the negotiation process; and already said that he hopes to meet again with the North Korean leader after Vietnam.

This underlines how much Kim has already received from Trump in exchange for the ambiguous pledges to “denuclearise” in the Singapore agreement. And this in a context too where there is also reported evidence that North Korea is continuing uranium enrichment and has stepped up missile production.

On a personal level, for instance, the previously isolated young leader has assumed significantly higher political importance on the international stage, from erstwhile allies and previous foes alike.This was highlighted in Kim’s post-Trump tour of Vietnam in recent days, his fourth foreign trip destination in less than 12 months after not leaving his nation’s borders for more than six years after assuming power.

Remarkable pivot

Indeed, both before and after last year’s Singapore summit with Trump, other major powers with a stake in the question of the future of the Korean peninsula, including Chinese President Xi Jinping, have begun jockeying for position as the region’s military and strategic landscapes are potentially recast in what South Korean President Moon Jae-in has said is the real end of the ‘Cold War’ more than a quarter of a century after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

One of the most spectacular features of this process, at least to date, has been the remarkable pivot of key powers towards greater engagement with Kim and the Pyongyang regime. All key parties sense significant new political and economic opportunities, and potentially risks, opening up under future sanctions relief.

Here it is no coincidence that Xi has now invited Kim for multiple trips to Beijing in 2018 and 2019. Moreover, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, who has met Kim in Pyongyang, has invited the North Korean leader to visit Putin in Russia.

The contrast between this feting of Kim, and the situation in 2017 when the Trump team was debating a pre-emptive attack against North Korea is striking. Trump’s state of the union address that year ratcheted up the rhetoric noting that Pyongyang’s “reckless pursuit of nuclear missiles could soon threaten our homeland... past experience has taught us that complacency and concessions only invite aggression and provocation. I will not repeat the mistakes of past administrations that got us into this dangerous position.”

The turnaround in spiralling tensions on the peninsula since then has been as potentially important as it was unexpected by many in late 2017. But it now looks potentially fragile again.

With the Trump-Kim Vietnam summit collapsing, what remains unclear is how big the potential downside risks are now in play. This includes the outside possibility of tensions rising again on the peninsula should the US-Korea dialogue break down completely.

While Trump currently appears keen to have a sustained strategic dialogue with Kim, especially in advance of his potential 2020 US presidential re-election campaign, the personal and political volatility of both of these leaders cannot be underestimated.

And if Kim ultimately reneges on any key pledges in the US president’s eyes, the political pressure will be on Trump again to ratchet up his position against Pyongyang, despite the warm words of 2018 and early 2019.

Trump remains under potential political pressure in the United States on this issue having drawn a political ‘red line’ as president over Pyongyang having nuclear weapons capable of striking the US homeland. And here he is well aware that missile tests in 2017 showed that Kim is close to developing a nuclear warhead capable of being fitted on to an intercontinental ballistic missile that can strike the US mainland.

Taken overall, while the Trump-Kim summit in Vietnam has collapsed, the wider grand diplomacy on the peninsula involving Washington, Beijing and Moscow following the Singapore summit will probably continue for the immediate future at least. However, while historic change could still be in the air, significant downside risks remain if the North-South dialogue ultimately proves a mirage, with the warming of relationships under way potentially going into reverse.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.