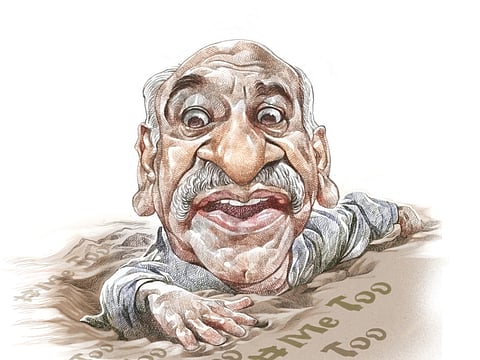

Tormentor in the newsroom

How one of independent India’s most powerful editors fell from grace in wake of the #MeToo movement

India’s Union Minister of State for External Affairs MJ Abkar stepped down from his post this week after a spate of allegations that he sexually harassed multiple woman journalists during his time as one of the country’s most powerful editors. In the newsrooms of Indian media in the 1980s, he was often referred to as Emperor Akbar. It was a sobriquet conferred upon him with unequivocal admiration. Here was this young, roaringly confident editor whose incisive sense of news gathering and packaging was leading to a sense of obsolescence in his competitors. Mobashar Jawed Akbar or MJ Akbar’s spectacular journey to fame, and eventual disrepute, began in the small town of Telinipura in West Bengal, where he was born on January 11, 1951.

With a Hindu paternal grandfather who was raised by a Muslim couple after being orphaned in communal riots, and who eventually embraced Islam, Akbar’s childhood acquired a multi-hued backdrop that played a significant role in fashioning his secular outlook.

After passing out from the Calcutta Boys’ School and later the Presidency College, Calcutta (1967—70), where he got a Bachelor’s honours degree in English, he began his journalism career with The Times of India in 1971. In 1976, he moved to Calcutta to join the Ananda Bazar Patrika (ABP) Group as editor of Sunday, a political weekly. The legend of Akbar was born.

Sunday became known for its blistering exposes and entrenched Akbar’s reputation as an editor with a ferocious intellect and a gimlet eye for perfection who would work till 3am every day, rewriting every single story in the publication.

In 1982, he launched The Telegraph newspaper and its energetic and explosive news reporting and presentation style became the gold standard for other Indian newspapers.

As he stood at the pinnacle of a well-earned success, Akbar’s eyes sighted, in the near distance, the shimmering spectacle of politics.

In 1989, he fought elections to the Indian Parliament and thus began his political journey. He soon became an unabashed admirer of Rajiv Gandhi but the latter’s assassination in 1991, left Akbar on the margins. In 1994, he quit politics and returned to journalism. He launched the newspaper Asian Age. Parting ways with the paper in 2008, he went on to launch more newspapers but these years, as it turned out, would be his personal nemesis in waiting.

The 90s also marked the beginning of his authorial prowess, beginning with his book Nehru: the Making of India in 1990. He went on to write nine more non-fiction works.

But his journey was changing him as much as he was changing his own path. In the words of one of his former colleagues, “He progressively became a different person. Even in office, the old equations began to change, and he started drawing people who shared his attitude to power closer to him.’’ His once ferocious and frank intellect veered towards bloated word craft.

By 2014, Akbar’s political north firmly pointed towards the BJP. He left journalism and joined the party as national spokesperson during the 2014 general elections and on July 5, 2016, was inducted into the Union Council of Ministers by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

And so we arrive in the now: In the last few weeks, as the #MeToo movement hit India, more than 20 women, who once worked with him when he was editor have accused Akbar of sexual misconduct. His resignation from the post of junior minister of external affairs from the BJP on Wednesday is, he said, to focus on cleaning up his besmirched image. Can he?

To quote from one of his articles, “Time heals, but, regrettably, rather more so in proverbs than in politics ... When the ship of state begins to leak, time, being a rascal, punctures a few extra holes in the hull. Any pragmatic captain knows that a limping ship must return to port or sink.”

Even if we assume that he mistakenly wrote a limping ship, as opposed to a listing ship, Akbar is right about time puncturing holes in its hull. Will his ship return to port or sink?

Time will tell.