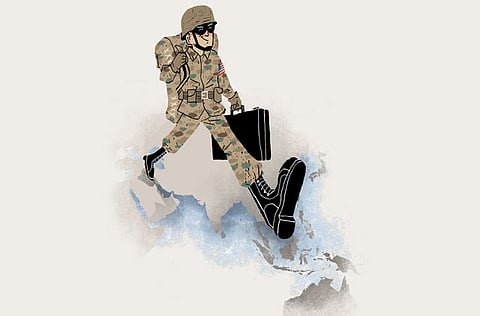

Tectonic US shift from the Middle East to the Pacific

Re-engagement in region will come at a very high cost if it is widely seen as a path to confrontation with China

For two years, the administration of US President Barack Obama has tried to convey a narrative in which it is winding up wars in southwest Asia and turning America's attention to its longer-term — and arguably more important — relationships in East Asia and the Pacific. In recent months, that narrative has gained the virtue of actually being true.

Now, the task will be to balance the need for responsible military drawdowns in Iraq and Afghanistan with a responsible build-up of activities in East Asia. And that means putting to rest fears that the US is gearing up for confrontation with China.

Obama's decision to break off talks with Iraq's government for a new agreement on the status of US forces there means that, after eight years, those troops are finally coming home (perhaps in time for Christmas). Critics claimed that Obama's administration had offered up Iraq to the Iranians. The ‘proof' was that Iraq's prime minister, Nouri Al Maliki — a leader who may be called many things, but certainly not pliable or pliant — did not deliver the rest of the country's political class to an agreement.

No support

Sunni leaders, who tend to be grouped under the banner of the Iraqi National Party, Iraqiya, made clear that they would not support the continuation of US troops on Iraqi soil, denying Al Maliki the backing that he needed to forge a broad-based coalition. Sunni leaders have often expressed support for US forces' presence in their country, but also believe that Iraq should no longer be a host to foreign troops.

Indeed, Iraq's implacable anti-American radicals are now both astonished and confused. Iraq's Sunni and Shiite militants agree on little, but one point of unison had been that the Americans would never leave their country voluntarily. Yet that is what is happening today.

Whether Americans will ever return to Iraq for exercises and training missions that exceed the scope of embassy-sponsored security-assistance initiatives remains to be determined. Iraq needs continued training programmes to manage its airspace, and its land forces must still overcome the Soviet model of massed artillery and armoured formations.

And so, with America's withdrawal from Iraq paving the way for the administration's tectonic policy shift on Asia, Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton headed West, confident that they would have a smooth journey. They did not. To the extent that Americans regard any foreign-policy speech as having relevance to their lives, Obama's economic message at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting in Hawaii was on message and on target: jobs, jobs, jobs.

But, soon after, when Obama arrived in Australia and Clinton landed in the Philippines, what looked like a clean narrative about the economy abruptly unravelled: Obama promised his Australian hosts that the US would station fewer than a brigade of US Marines in far-off Darwin to train and exercise. No one could possibly believe that this step would be sufficient to allay whatever concerns the Obama administration and America's Asian allies have about China's growing military power, but that is how the US press played it.

Productive relationships

When combined with Clinton's crowd-pleasing appearance on a warship in Manila Bay, and her use of the term "West Philippine Sea," the economic narrative stood little chance. The new storyline was that the US had started pulling out of Southwest Asia for the purpose of confronting China. Even the administration's deft and courageous move to send Clinton to Myanmar, following Myanmar's opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi's release from detention and decision to rejoin the political system, was portrayed as another effort to poke China in the eye. America's re-engagement in the Asia-Pacific region is welcome and overdue.

But re-engagement will come at too high a cost if it is widely seen as a path to confrontation with China, rather than overdue attention to everyone else. The US and the Asia-Pacific countries need to maintain productive relationships with China, which is becoming more complicated for everyone as China plunges into a period of internal introspection about its future.

How China emerges from this process, and how it behaves in its neighbourhood — and globally — will determine much about what the world will look like in the medium and long-term. We need to avoid creating self-fulfilling prophecies that stem from our deepest fears.

— Project Syndicate, 2011

Christopher R. Hill, former US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia, was US special envoy for Kosovo, a negotiator of the Dayton Peace Accords, and chief US negotiator with North Korea from 2005-2009. He is now Dean of the Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver.