Suu Kyi's action on Rohingya issue: How Nobel is that?

Myanmar leader has lost her conscience and principles when it comes to the horrors being inflicted now on the Rohingya

For a woman who has spent almost a seventh of her life living under house arrest or the inside of a prison cell, you’d imagine that Aung San Suu Kyi might have learnt a thing or two about human condition.

And for a woman whose own struggles have been recognised by the global community — and awarded her a Nobel Peace Prize too in 1991 for her dedication to freedom, justice and democracy — you’d think she might have appreciated the power of international persuasion.

Or for a woman who was just two when her father was assassinated as he led Burma’s (Myanmar’s) independence struggle from British colonial rule, she’d remember a thing or two about oppression and social justice.

And for a woman’s whose own state has struggled to gain freedom from its generals and junta, and whose discriminatory laws and constitution make it impossible for her to become president of Myanmar, you might be forgiven for thinking that Suu Kyi would understand the plight of those who are shunned, oppressed and made non-persons by the very government she acts for as State Councillor.

Wrong, wrong, wrong and wrong.

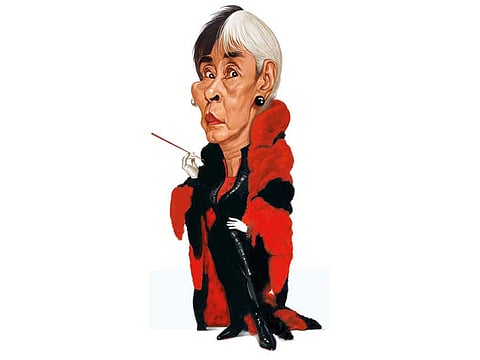

Right now, Suu Kyi is acting as a modern-day Cruella DeVil, more interested in maintaining her status than standing up for the Rohingya. Like the Disney character that’s more interested in keeping her 101 Dalmatian puppies together, she has seemingly forgotten every principle and footstep that has brought her this far in Myanmar.

Ethnic cleansing

Yes, you know she’s lost touch with reality when she takes a page out of a White House communications book and labels reports of 148,000 Muslim Rohingya fleeing Rakhine into neighbouring Bangladesh since August 25 as fake news, and blaming “terrorists” for spreading an iceberg of disinformation about the crisis. That’s not sitting well with Antonio Guterres, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, who is warning that the crisis is as close to ethnic cleansing as you can get.

While Suu Kyi fiddles, Rakhine is burning.

One survivor said military and locals, armed with swords, spears, sticks and guns had arrived in his village just after Friday prayers, shooting into the air and setting the village ablaze. “As soon as they arrived, they began to burn houses, starting with Shukur’s,” he said in footage taken in a village where the homeless survivors have taken temporary shelter. Some people were allowed to leave to the east of the village, but not everyone escaped with their lives, he said. They had to swim to safety through shrimp farming ponds flooded by high tides, and some never made it out of their houses. “People lost their lives in the attack. some drowned while crossing the water, some could not get out of their homes and died in the fire. Our whole village was burned down.”

In one small hamlet, a brief inspection by two soldiers lulled residents into a false sense of security.

“After walking around and checking inside the village, they left, taking a cow from a widow. We thought they would become calm, but after some time they surrounded our village from all sides and started shooting at the villagers, men, women, children even infants,” said one woman.

There are reports of mass graves and mass killings. And with Suu Kyi standing by, she’s a model to the very junta she replaced.

Her father, General Aung San, was assassinated during Myanmar’s transition from British rule in July 1947, just six months before independence.

In 1960, she went to India with her mother Daw Khin Kyi, who had been appointed Myanmar’s ambassador in New Delhi.

Four years later, she went to Oxford University in the United Kingdom, where she studied philosophy, politics and economics. There she met her future husband, academic Michael Aris. After stints of living and working in Japan and Bhutan, she settled in the UK to raise their two children, Alexander and Kim, but Myanmar was never far from her thoughts. When she arrived back in Yangon in 1988 — to look after her critically ill mother — Myanmar was in the midst of a major political upheaval. Thousands of students, office workers and monks took to the streets demanding democratic reform.

Inspired by the non-violent campaigns of US civil rights leader Martin Luther King and India’s Mahatma Gandhi, she organised rallies and travelled around the country, calling for peaceful democratic reform and free elections.

But the demonstrations were brutally suppressed by the army, who seized power in a coup on September 18, 1988. Suu Kyi was placed under house arrest the following year. The military government called national elections in May 1990, which Suu Kyi’s NLD convincingly won — however, the junta refused to hand over control. Suu Kyi remained under house arrest in Yangon for six years, until she was released in July 1995. She was again put under house arrest in September 2000, when she tried to travel to the city of Mandalay in defiance of travel restrictions.

House arrest

She was released unconditionally in May 2002, but just over a year later she was put in prison, following a clash between her supporters and a government-backed mob. She was later allowed to return home — but again under effective house arrest.

She was sidelined from Myanmar’s first elections in two decades on November 7, 2010, but released from house arrest six days later. Her son Kim Aris was allowed to visit her for the first time in a decade. As the new government embarked on a process of reform, Suu Kyi and her party rejoined the political process.

In 2015, the military-backed civilian government of President Thein Sein said a general election would be held in November of that year — the first openly contested election in 25 years.

Soon after the November 8 vote, it became clear the NLD was headed for a landslide victory. On November 13, the NLD secured the required two-thirds of the contested seats in parliament to win a majority in what was widely regarded as a largely fair vote — although there were some reports of irregularities.

“I could not, as my father’s daughter, remain indifferent to all that was going on,” she said in a speech in Yangon on August 26, 1988, beginning her struggle against the junta.

Too bad she’s forgotten that.

— With inputs from agencies