Punishing Mugabe will not help Zimbabwe

The idea of cushy exile may appal. But history shows that societies in transition may be wise to sacrifice the urge to see their former dictators brought to justice

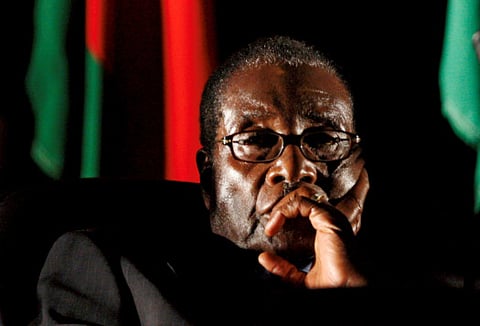

Of all the questions hanging over the dramatic, uncertain events in Zimbabwe, there is one that looms especially large. It is the same question that arises every time, and in every place, a long-established dictatorship is toppled. What to do with the once-supreme leader himself? Perhaps, as the Guardian’s Africa correspondent Jason Burke suggests, Robert Mugabe will stay on as a “figurehead”, while those who ousted him get on with governing the country. Alternatively, there’s the suggestion floated in a BBC interview by Tendai Biti, a Zimbabwean opposition leader and former finance minister: That Mugabe head for exile in Singapore, which has served in recent years as a virtual “second home” for the 93-year-old. If Mugabe and his wife Grace wanted to go there, said Biti, “no one should prevent him”.

I wonder how either scenario would sound to those Zimbabweans who blame Mugabe for reducing their once-prosperous country to penury. Or those whose loved ones were jailed, beaten or tortured on Mugabe’s orders. Surely, they would very much want to prevent the dictator either retaining his title or enjoying his final years in comfort and safety in a foreign capital. Surely they would want to see him answer in court for what he has done. Surely they would yearn for justice.

Yet, perhaps Biti had in mind the experience of other nations, in Africa and beyond. Contrast, for example, the fate of two nations whose leaders were ousted during the Arab spring of 2011. In Libya, Muammar Gaddafi was hunted down and caught by rebels, who, in the name of revenge, beat him to a brutal death. In Tunisia, Zine Al Abidine Bin Ali ended his 23 years in power by boarding a plane to exile. Libya remains a country in turmoil, while Tunisia boasts that it has had elections and is fairly stable — and the one success story of 2011.

Transition from dictatorship

Now perhaps that is a coincidence, owing nothing to the very different fates of the two deposed leaders. But it’s undeniable that societies that make the transition from dictatorship often have to sacrifice the urge to see the dictator himself brought to justice. In Chile, there were tens of thousands of families who saw Augusto Pinochet as the murderer of their son or daughter, father or sister.

And yet, in order to see him removed from power, they had to watch as he was granted the special status — initially anointed a “senator for life” — that would allow him immunity from prosecution. As a would-be Chilean prosecutor ruefully put it: “Our country has the degree of justice that political transition permits us to have.”

It is an age-old tension, known to all societies emerging from conflict. Sometimes it means allowing the release of prisoners guilty of acts of great violence — witness the Good Friday agreement between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and between the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom. Sometimes it means allowing the most brutal dictators to walk away scot-free, never brought to account.

The bleak truth that Zimbabwe might be about to demonstrate once more is that, even though it is human to long for justice and peace, we can often have one or the other — but not both.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Jonathan Freedland is a senior columnist and writer.