Pakistan’s angel of mercy — Abdul Sattar Edhi

The death of the humanitarian last Friday shocked millions, who took inspiration from his life’s work

When a high-ranking Pakistani politician visited the country’s best-known ailing campaigner for humanitarian causes last month, with an offer of medical treatment abroad on an unlimited budget, the response was telling. Even in his dying days, Abdul Sattar Edhi rejected the pledge from former interior minister Rahman Malek, delivered on behalf of Pakistan’s former president Asif Ali Zardari, for treatment abroad. Instead, he chose to be treated at home and in a government-run facility.

His twice-weekly visits for dialysis at the well-reputed Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation in Karachi instantly attracted prayers from ordinary Pakistanis. It was therefore hardly surprising that Edhi’s death last Friday, following a prolonged battle with kidney failure, shocked an overwhelmingly large number of Pakistanis. He was almost a universally-loved individual in a usually divided country, who gave inspiration to Pakistan’s 200 million people.

It was in recognition of Edhi’s services to humanity that he became just the fifth man in Pakistan’s history to be given a state funeral — the other four recipients of this honour in the previous 70 years being Qaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s founding father; Liaquat Ali Khan, the first prime minister; General Zia ul-Haq, the late military ruler, and General Asif Nawaz Janjua, a former well-respected army chief.

Edhi’s journey to stardom began on a humble note in the 1960s when he collected just enough money through his charity work to buy himself a battered old, van, which he turned into an ambulance. Today, that small beginning has spawned into one of the world’s most impressive humanitarian services offering 1,500 ambulances, running orphanages, support services for hospitals and nursing care, and adoption services for abandoned infants. His iconic status came to be described through popular titles bestowed upon him such as the Angel of Mercy and Father Teresa — after the late Mother Teresa, who devoted her life to caring for the downtrodden in the Indian city of Kolkata.

For visitors to Edhi’s humble offices in central Karachi, becoming overwhelmed was never difficult. He operated out of a small office and slept in an 8ft-by-8ft room right next door.

Parental love and affection

Charity work took Edhi beyond Pakistan to offer his services in conflict zones such as Lebanon, right at the peak of a bloody conflict. But the universality of his message went far beyond. Mourners who gathered at Edhi’s funeral were quickly joined by millions of others across the world, who came together to remember his services. In a country where the ruling structure is dominated across the board by self-serving politicians, Edhi’s demise has thrown up a pertinent question: Exactly how did his miracle come about?

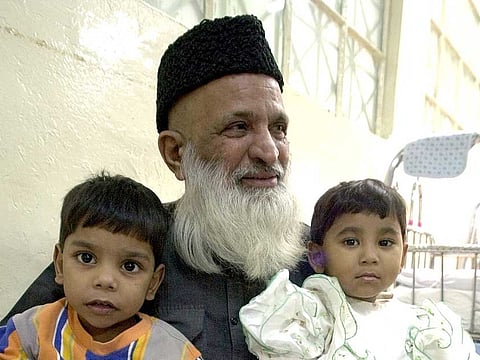

The answer to that riddle could well be found through a quick review of Edhi’s life, work and style. During his many visits to Edhi village — a large orphanage outside Karachi along the super highway — his presence would quickly create a carnival-like atmosphere. Known to many of the orphanage’s inhabitants as ‘Baba’, Edhi’s arrival provoked the orphans to quickly surround him. His almost parental love and affection immediately translated into the distribution of candies and other gifts — an instant reminder of a sharp contrast to the abuse that orphans on the streets of Pakistan receive on a daily basis.

And last, but not the least, Edhi’s all-too-visible integrity earned him not only the respect of Pakistanis, but also their generous support. The multifaceted dimension of his work ranged from providing jhoolas (cradles), outside his network of Edhi centres across Pakistan, to the network of ambulances zipping past. In 2005, the earthquake that shook northern Pakistan, killing at least 70,000 people, saw Edhi personally lead his group of volunteers to brave the winter chill of Pakistan’s northern areas. They were among the first line of relief providers. Similar tales came about following other calamities such as catastrophes caused by floods.

Following his demise, many Pakistanis have pondered over the future of the Edhi Foundation, whose responsibilities have now fallen upon his wife, Bilquis, a nurse and also a humanitarian relief campaigner herself, and their son, Faisal. The greatest assurance of the continuity of Edhi’s miraculous legacy perhaps lies in this success story more than anything else. As success often breeds success, it is likely that in this case too, Edhi’s many supporters and his successors will keep on reminding themselves to continue building on his good work.

And his final resting place within Edhi village will indeed remain a place of frequent visits. The orphans within that facility will find it hard to forget their Baba who brought them security, joy and the hope of carrying on successfully in life.

Farhan Bokhari is a Pakistan-based commentator who writes on political and economic matters.