Muslims have more visibility than ever, but can we praise it

Muslims must not compromise identity for sake of prominence in systems that exploit them

HIGHLIGHTS

- We live at the cusp of both unprecedented Muslim visibility and heightened anti-Muslim racism.

- Raising Muslim representation in popular culture can have devastating consequences if it remains only skin-deep.

- Fighting for inclusion in the very systems that require exploitation and even violence against our own communities is a step back.

- More hijab-wearing women in police or the military is a “win” for inclusion, but these institutions commit violence against Muslim communities domestically and abroad.

- Anti-Muslim violence is holistic and systemic; efforts to challenge it cannot be surface-level and compromised.

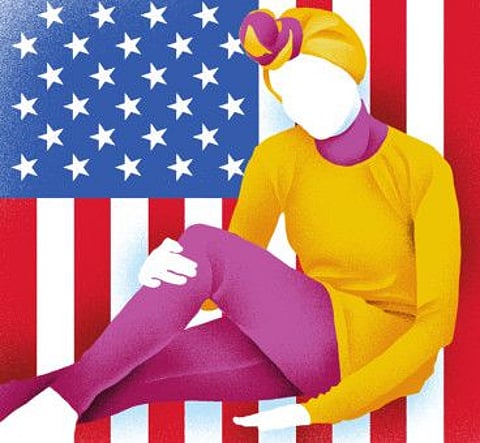

Between a burkini featured in this year’s Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue and the New Haven mosque set ablaze last month, Muslims in the United States occupy a particularly demanding moment in history. As we near the end of Ramadan, we live at the cusp of both unprecedented Muslim visibility and heightened anti-Muslim racism. If we are not careful, these new modes of representation may contribute to the rise of anti-Muslim racism, rather than combat it.

As a visibly Muslim woman born and raised in Oklahoma, I never saw anyone who looked like me shown in a positive light — if even at all — in the magazines I stashed under my bed or the television shows I consumed. Although I still had Muslim role models I looked up to (such as my mother), I grew up feeling unconnected to my surroundings.

Muslim representation in popular culture

My classmates, fed on the same media, would try to convince me that I was foreign; that nothing was made for me or people who looked like me. Being able to see a gorgeous, hijab-wearing Muslim woman of colour such as Halima Aden on the covers of the magazines I picked up as a kid could have helped challenge my and my peers’ understanding of who is allowed to feel at home in the United States.

Yet although raising Muslim representation in popular culture is an important and necessary step forward, it can have devastating consequences if it remains only skin-deep. Representation must also be accompanied by a rise in unapologetic Muslim voices and structural challenges to systems that create and perpetuate anti-Muslim violence.

Hijabs become synonymous with the Muslim woman, erasing the complexities of her identity — ethnicity, race, displacement, culture and varied life experiences. The spiritual value of the hijab is defined and framed by marketers who may have no understanding of the significance it has to many Muslim women.Hoda Katebi

Today, major department stores are releasing Ramadan collections and modest-wear lines, and the media celebrates hijab-wearing models and influencers as the faces of fast-fashion brands. But too often, the conversation ends there: Our representation stops at the cash registers. And fighting for inclusion in the very systems that require exploitation and even violence against our own communities is not a step forward, but a step back.

While we are celebrating a Nike Pro hijab and Mango’s Ramadan collection, we know that Muslim garment workers in sweatshops are exploited to make these clothes. While we view more hijab-wearing women in police departments or the military as a “win” for inclusion, we ignore the fact that these institutions commit violence against our communities domestically and abroad.

Hyper-simplification of Muslim identity

As Muslims fight for a seat at the table to challenge white supremacy and popular nationalism, have we made sure that we are not oppressing our own communities in the process? Anti-Muslim violence is holistic and systemic; our efforts to challenge it cannot be surface-level and compromised.

What we are experiencing right now is a dangerous game of essentialisation: the hyper-simplification of Muslim identity down to a headscarf. Hijabs become synonymous with the Muslim woman, erasing the complexities of her identity — ethnicity, race, displacement, culture and varied life experiences. The spiritual value of the hijab is defined and framed by marketers who may have no understanding of the significance it has to many Muslim women. Brands whose clothes were made by Muslim women in sweatshops put hijabs in their advertisements to make themselves seem “diverse” and Muslim-friendly.

Featuring a burkini in Sports Illustrated can help to slowly normalise a form of swimwear that, because of its association with Muslim life, sparks controversy throughout Europe. But it is a complicated form of representation, given the magazine’s often sexist take on the female body and its photos shot with a male audience in mind. The magazine is not one that I would have picked up as a young Muslim girl in Oklahoma and felt seen or represented by.

Also Read: The story of a millennial American Muslim

Also Read: A rendezvous between a Muslim and a Jew

Also Read: Growing weary of the hijab fetish

Can we really praise Muslim visibility when it comes at the expense of our global community? Is hijab visibility worth celebrating if its purpose is only to make wearing one more palatable to non-Muslims? What kind of representation works to challenge systems of violence, and what kind makes us complicit?

It is difficult to deny the value of increased Muslim visibility in popular culture, especially within a heightened climate of anti-Muslim racism. But that does not mean the bar should be lowered. Muslims appearing on the covers of and in magazines can be a step in the right direction, but only if these features uplift our voices rather than rely on compromised notions of identity. Positive representation looks less like a Muslim woman in an H & M advertisement and more like Muslim garment workers in Bangladesh and Indonesia leading movements to end gender-based violence in H & M’s factories.

From politics to fashion, representation is an important component for achieving a world without structural racism. It is important that Muslims do not compromise on our identities for the sake of visibility in systems that continue to exploit us. The choice of how we move forward — and with whom, for whom and at whose expense — is a decision that we as Muslims have to make right now.

— Washington Post

Hoda Katebi writes the fashion publication JooJoo Azad and is founding member of the clothing manufacturing cooperative Blue Tin Production.