Muhammad Ali symbolised Africa’s moment of glory

From his first rumble on the world stage to his last breath, he remained the most adored figure and best global icon the world has ever known

As a transcendent sports legend and an iconic cultural figure, Muhammad Ali’s story reverberated through the African continent and inspired the African youth in various aspects.

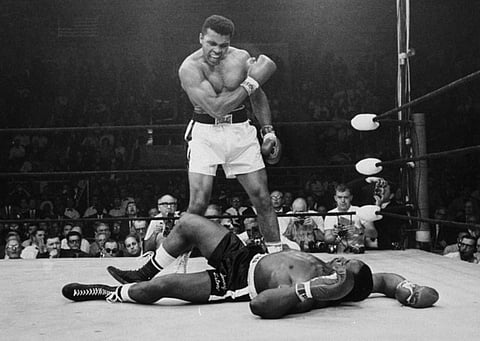

Ali’s rise to world prominence in the 1960s coincided with the pinnacle of Africa’s independence euphoria when most of the African nations threw off the yoke of European colonialism. When Ali danced and shouted “I am the greatest” after defeating Sonny Liston in 1964 and winning the world heavyweight championship, Africa was also going through its historic “Wind of Change” as described by then British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan.

This was the time when black intellectuals were pushing black consciousness, when the power of African-American music came to Africa, when Afro hair style, later epitomised by Angela Davis, was a popular fashion. It was the time when college students were engrossed with the works of revolutionary intellectuals such the Guyanese historian Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and the Afro-Caribbean psychiatrist, philosopher Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth as well as the cannons of W.E.B. DuBois, a doyen in black history, as well as the poetry of the French Negritude movement led by the Senegalese Senghor, the Martinican Poet Aime Cesaire and Leon Damas of French Guiana.

It was a time when Africa was led by towering figures such as King Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, Leopold Senghor of Senegal, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Abubakar Balewa of Nigeria, Patrice Lumumba of Congo, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Jamal Abdul Nasser of Egypt, Ahmed Seketoure of Guinea, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya and Adam Osman of Somalia.

But despite these independence heroes, it was the struggle of the American civil rights movement of the American blacks that loomed large in the African mind. It was due to this that Muhammad Ali’s dramatic and phenomenal ascension to world focus embodied by his soaring athletic talent, his fight for justice, his youthful vitality, and his fearlessness against the enormous socio-political challenges of the time, had become recognised as a natural extension of the African people’s struggle for freedom against the white European domination.

African people, therefore, not only followed Ali’s story with great enthusiasm but they also internalised the struggle of the civil right leaders such as such Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and others. However, it was Ali’s larger-than-life persona that mesmerised the youth and adults alike. Ali’s pictures where everywhere and one could see people glued to radios whenever Ali was fighting for a title.

Ali’s refusal to fight in Vietnam echoed with Africa’s support for the Vietnamese people and further elevated Ali’s status in the eyes of not only the African people, but all peoples in the colonised world. This was at the height of the Cold War and newly independent African countries were instrumental in the non-aligned movement that was created to charter a third way for the newly found states. Hence, Ali emerged as a powerful voice for all oppressed people in the world. He has become the greatest Ambassador for Africa by declaring “I am an African and my proper name is Muhammad Ali” during his visit to Africa in 1964 where people thronged at wherever he set foot in Ghana, Egypt and Nigeria.

In Ghana, Ali was given a royal welcome with an entourage of cabinet ministers and thousands of people receiving him at the airport. He was received by both president Abdul Nasser of Egypt and Nkrumah of Ghana in their presidential palaces.

President Nkrumah directed the government’s media to promote the American champion as an African hero, “a source of inspiration to the youth of the world”.

Summing up Africa’s expectation of Ali, a writer for Ghana’s state-owned Daily Graphic at the time wrote: “If there is one man who can assist positively to bring about [Nkrumah’s] cherished aims of projecting the African personality” — an Africa freed from the vestiges of colonialism — and disprove “the superiority complex of the white man, he is Mohammed Ali (Cassius Clay).”

The mutual adoration between Ali and Africa reached its peak at the historic boxing event ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ where Ali defeated George Foreman to the delight of 60,000 mostly African spectators in Kinshasa, Zaire, currently Democratic Republic of Congo.

Apart from Africa, Ali has become a popular household name in most of the developing countries, particularly in the Muslim world as he emerged as the best-known Muslim celebrity around the globe. Only Ali could articulate this pride and sense of belonging with his renowned eloquence and humour by saying: “I can’t name a country where they don’t know me. If another fighter’s going to be that big, he’s going to have to be a Muslim, or else he won’t get to nations like Indonesia, Lebanon, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Syria, Egypt and Turkey — those are all countries that don’t usually follow boxing.”

From his first rumble on the world stage to his last breath, Ali remained the most adored figure and best global icon the world has ever known. And as United States President Barack Obama said in his tribute, “Muhammad Ali shook up the world,” Africa had its lion’s share of delight.

Bashir Goth is an African commentator on political, social and cultural issues.