Mousa envisions vigorous and peaceful Middle East

Egypt's presidential frontrunner warns things could go ugly if the Palestine question is not dealt with fairly

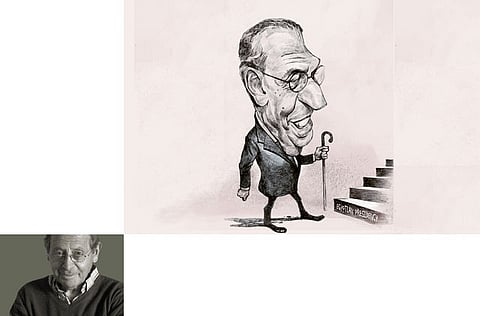

Amr Mousa, 74, the front-runner in the contest for the presidency of post-revolution Egypt, has called for a renegotiation of the military annexes to the Egyptian-Israel Peace Treaty of 1979.

“The Treaty will continue to exist,” he told me in an exclusive interview on September 10, “but Egypt needs forces in Sinai. The security situation requires it. Israel must understand that the restrictions imposed by the Treaty have to be reviewed.”

Mousa was speaking in Geneva a day after delivering the keynote address at the annual conference of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), a leading London-based think tank.

Under the Peace Treaty — signed in Washington on March 26, 1979 by President Anwar Sadat of Egypt and Prime Minister Menachem Begin of Israel, and witnessed by US President Jimmy Carter — the Sinai Peninsula, captured by Israel in the 1973 war, was returned to Egypt. In return, Egypt agreed to its demilitarisation.

Last January, when protests first erupted against former president Hosni Mubarak, leading to his downfall 18 days later on February 11, Israel allowed Egypt to move a few hundred troops into Sinai — for the first time since the treaty was signed 32 years ago. Egypt deployed two battalions, about 800 soldiers, in the Sharm Al Shaikh area on Sinai’s southern tip, far away from Israel. But, in calling for a revision of the military annexes, Mousa clearly has something more radical in mind.

The Egyptian revolution has led to acute tension between Egypt and Israel, and to great concern in Israel and Washington about the future of the peace treaty. By removing Egypt from the Arab line-up, the treaty gave Israel three decades of military hegemony in the region. For the Arabs it was a disaster. It exposed them to Israeli aggressions, such as the repeated invasions of Lebanon, the siege and invasion of Gaza, and the relentless seizure of Palestinian land on the West Bank.

On the night of Mousa’s address to the IISS in Geneva, protesters in Cairo stormed the Israeli embassy. The ambassador and his staff fled to Israel. Egyptian opinion was outraged by the killing on August 18 of five Egyptian policemen by Israeli forces inside Egyptian territory, north of the Egypt town of Taba and the Israeli town of Eilat. The policemen were killed when Israeli forces crossed the border in pursuit of fighters who had attacked Israeli vehicles on the road to Eilat, killing eight Israelis.

“Israel made a great mistake when the Egyptian revolution erupted,” Mousa told me. “It claimed that the revolution had nothing to do with Palestine. I said: ‘Just wait!’” Israel is playing havoc with the stability of the Middle East because it doesn’t appreciate the extent of the changes sweeping the region. It thinks it can go back to business as usual. This is impossible.

“Palestinians are right to seek recognition of their statehood at the United Nations this month. They have no other option. No other offer has been made to them. The peace process is dead. The time has come for the European powers to understand that keeping Palestine on the back burner has been a grave strategic mistake.

“All European states should support the Palestinian move. One cannot close all doors to the Palestinians and expect them to submit. They will not.”

Uprightness

Mousa’s views are important because he stands a strong chance of being elected president of Egypt next year. Other leading contenders are Mohammad Al Baradei, 70, the former head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, and Abdul Muneim Abul Futuh, 60, a medical doctor, with a long history of opposition to the Mubarak regime, who is thought to be a member of the moderate wing of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Al Baradei is admired by educated young people, but he has spent much of the past 35 years out of Egypt and can have little first-hand knowledge of Egypt’s domestic problems. As for Dr Abul Futuh, there is some doubt whether the Muslim Brotherhood would want one of its members to assume responsibility for the awesome task of tackling Egypt’s immense economic and social problems.

Depending how they fare at the coming parliamentary elections, when it is estimated they might win 30 to 40 per cent of the vote, the Muslim Brotherhood may prefer the premiership to the presidency, or might even be content with two or three ministries.

Mousa could be a strong president, acceptable to a wide range of opinion. He is known to prefer a presidential to a multi-party parliamentary system of government, which he fears might result in weak, short-lived coalition governments. In standing for president, he has said that he will seek only a single four-year term.

He was not a member of Mubarak’s ruling National Democratic Party, nor was he part of the corrupt elite around the former president and his son. He has a reputation for probity and for understanding Egypt’s grave domestic problems. As he told the IISS in his keynote address, 50 per cent of Egyptians live in poverty, while 30 per cent are illiterate. The country has to be rebuilt. He is confident it can be done.

He has had extensive international experience having been Egypt’s representative at the UN from 1981 to 1983 and again from 1986 to 1990, before serving as Egypt’s foreign minister for ten years from 1991 to 2001, and then as secretary-general of the Arab League for another 10 years from 2001 to 2011. He opposed the American invasion of Iraq in 2003 and has been a consistent critic of Israel’s occupation and dispossession of the Palestinians. The Arab League under his direction approved Nato’s operations against Muammar Gaddafi’s regime in Libya.

Last April, Mousa called for a no-fly zone over Gaza to protect it from Israeli bombardment. Israel’s ‘Operation Cast Lead’ — its brutal assault on Gaza in December-January 2008-9, which killed some 1,500 Palestinians and caused immense material damage — did a great deal to undermine its relations with both Egypt and Turkey, the two major powers of the region with which it used to enjoy close relations. Many Egyptians are profoundly ashamed that Mubarak colluded with Israel in the prolonged siege of Gaza.

Mousa would not be a belligerent President. He wants a settlement of the Israel-Palestine conflict on a win-win basis, as proposed in the Arab peace initiative. He advocates setting up a regional security system, to include both Israel and Iran on the basis of a WMD (weapons of mass destruction) free zone. His vision is of a new, vigorous, stable and peaceful Middle East. “The people cannot stand being robbed of their future any longer,” he says.

Mousa is a profoundly reasonable and moderate statesman. So is Mahmoud Abbas, president of the Palestinian National Authority, who is seeking UN recognition for a Palestinian state. If Israel wants long-term security and full acceptance into the region, it should heed their views.

As Mousa told me last weekend, there is a popular consensus in the Arab world that the Palestine question must be dealt with properly and fairly. “If this does not happen, things will turn ugly,” he said with great emphasis.

Patrick Seale is a commentator and author of several books on Middle East affairs.