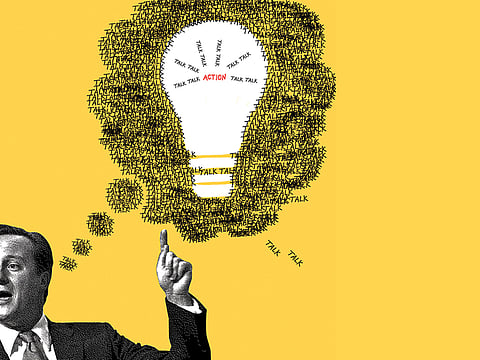

Ideas, but little action from Cameron

The British prime minister has revealed where he wants to get to, but he hasn’t yet pointed out the road that leads to it — much less started the journey there

Over dinner, long before he entered Downing Street, David Cameron was once asked why he wanted to be prime minister. “Because I’d be good at it,” he replied. He was right. Cameron is good at it, in the managerial sense. It is not just his impressive stagecraft, his ability to project calm assurance and authority, especially in moments of drama, tension and national attention.

According to civil servants who work closely with him, as they did with earlier British prime ministers, he takes even life-or-death decisions coolly, discharges his duties with steady efficiency, ploughing through his papers, delegating shrewdly to ministers and — but for the odd tantrum — he does it all with good humour and poise. Cameron promised “quiet competence” and his Downing Street operation largely reflects that. Philosophically, too, Cameron wears his office lightly. Commentators have almost given up talking about the Big Idea behind the Cameron premiership, accepting that pragmatism prevails. The big idea is that there is no big idea. Strategy and ideology are far less important to the prime minister than good judgement and common sense: Just take things as they come, and do your best.

Is it reasonable to criticise a prime minister for making it up as he goes along when that’s what you do yourself? Besides, Cameron might retort that the results of his temporising and improvising have been good enough so far. And not just in terms of governing but electorally, too. Cameron may today glory in his pragmatism, but he’s neither devoid of big ideas nor averse to pursuing them. It’s just that his last experience of trying to turn lofty concepts into political reality was a painful and frustrating one: You may not remember the Big Society, but Cameron does — wistfully.

Nonetheless, there is a Cameron vision, a set of ideas and objectives to which he is passionately committed. Sadly, we’ve only caught sight of that agenda twice since the general election, and only then in speeches. In terms of action, there is little sign of it. The agenda can loosely be described as One Nation Conservatism. The speeches were on returning to No 10 after the election (“It means giving everyone in our country a chance, so no matter where you’re from you have the opportunity to make the most of your life”) and at the Tory conference in October (“Britain has the lowest social mobility in the developed world. Here, the salary you earn is more linked to what your father got paid than in any other major country. For us Conservatives, the party of aspiration, we cannot accept that”).

This is the basis of a Big Idea, and a good one too. There is indeed a sound Conservative case for doing more, much more about Britain’s woeful levels of social mobility, to ensure that where you start off in life doesn’t dictate where you end up. Where are the policies that might actually increase the chances of clever kids from poor homes ending up as doctors and judges and chief executives and, yes, prime ministers? Bluntly, where’s the leadership?

Cameron has told Britons where he wants to get to, but he hasn’t yet pointed out the road that leads to it, much less started the journey there. One of Cameron’s team privately expresses frustration about the reluctance of “the boss” to take ownership of the things he says drive him, especially the ideas and issues he spoke of in the conference speech. Several Cabinet ministers were elated by that speech, daring to hope that Cameron was embarking on a real crusade to deliver on his private promises to make Britain a more meritocratic society.

Some of those same ministers, who saddled up to follow him, now worry about how little No 10 has done to follow up on the vision described. Some of this is just a question of priorities. Terrorists are killing people on European streets. British jets and special forces are deployed in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan. Britain’s place in the European Union (EU) hangs in the balance. Dealing with immediate crises inevitably means there’s less time for less urgent matters. But that’s the nature of the job, and the office of prime minister must surely be about more than crisis management.

Aversion to “-isms” doesn’t have to mean avoiding any attempt at effecting serious social and economic change. The lack of delivery on “One Nation” is also one of the baleful consequences of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party.

Cameron really is at his best when his back is to the wall, when he’s under pressure. And Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour Party leader, puts him under no pressure whatsoever. There is no incentive for Cameron to deliver on those good words — and no penalty for failing. Before the next election, Cameron will leave office without articulating or implementing “Cameronism”. That is no bad thing. Nor should he worry about his legacy: Even if he ends up overseeing the United Kingdom’s departure from the EU, as long as it remains a United Kingdom he will deserve the approval of posterity. But if he departs without seeing through his fine words on equality and aspiration, without taking Britain at least a little closer to being “One Nation”, where your place in life owes more to your talents than your birth, how will he fare in the judgement that matters more than any other — the one he passes on himself? There is more than one way to be a good prime minister.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2015