How Myanmar is charting its own course amid global protests

Military takeover has put ASEAN, of which Myanmar is a member, in a state of dilemma

Myanmar’s generals who took over direct power after dismissing the Aung San Suu Kyi led National League for Democracy (NLD) government, though surprised at the level of resistance, are by no way shaken. Citing provisions of the constitution, which allowed declaring the state of emergency for one year, the generals have nearly quelled the spontaneous people’s resistance against the military action. Hopes of those within the country and outside are fading over the possibility of a relatively quick return to the civilian rule.

During this time the western powers have imposed sanctions, the ten nations Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), of which Myanmar in a member and many other countries have implored the generals to roll back the military rule. During the middle of June, the UNGA adopted a resolution, albeit a weak one, to secure broad support, condemning the military in Myanmar for its actions. With 36 abstentions, the vote is unlikely to persuade the military to revert to civilian led government.

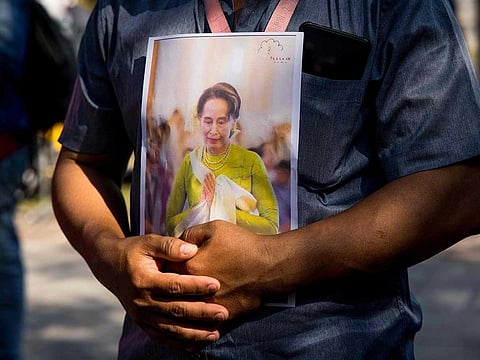

The takeover occurred upending the overwhelming victory in general elections, for the NLD, the party of Nobel laureate Aung Sung Suu Kyi. They were to be sworn for the new term on February 1. Declaring emergency, the military arrested most of the leadership and those who were able to escape have formed the National Unity Government (NUG), which no country has yet recognised.

A tight grip

Myanmar generals have run the country since 1962. The constitution adopted in 2008 paved the way for a semblance of civilian governance but guarantees complete autonomy and veto over any significant constitutional amendments to the military. Controlling 25 per cent of the assembly seats, the military never really loosened its grip on power nor did the generals really embrace the idea of majority rule.

Tension was building up between Aung Sung Suu Kyi and the military in the lead-up to the elections held earlier this year. She had been seeking several constitutional amendments aimed at reducing military’s influence over governance. The military, which controls quarter of the assembly seats in the parliament, took note of her intentions and struck before she could be sworn for the second term.

Keeping a tight grip, many observers were sceptical of military’s intent to democratise through elections. By co-opting her in a quasi-democratic arrangement, the military played its cards well to acquire international acceptance and aid following increasing pressure from global community.

The military takeover has put the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), of which Myanmar is a member, in a state of a dilemma whether to take a firmer stand or to stay clear of the internal developments of the member states, which they are obliged to do under the charter. Members’ comments, for now have been subdued leaving doors open for engagement with the generals.

ASEAN’s consensus rule means slow progress, which has as a consequence, allowed General Min to consolidate his authority than to restore civilian rule. Even though the ASEAN has not formally recognised the new regime, his reception on arrival at the ASEAN meeting in Jakarta had all the trappings of a head of state.

Moreover, the organisation did not invite the representative of the deposed government, which sends a clear signal over ASEAN’s line of action calling for cessation of violence, dialogue to find a peaceful solution and appointment of a special envoy. The consensus made no mention of the release of prisoners who now number about 6,000.

Differences in ASEAN

Within the ASEAN there are differing opinions on how to handle the situation. While Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore support stronger action, others led by Thailand, where the government is headed by a former general, more or less acquiesce with what has happened.

Myanmar’s case may well be representative of trends in Southeast Asia. Of the ten ASEAN states just two or three can claim to be practicing the western pattern of democracy. The rest are either military backed or a hybrid democracy.

The US and other Western powers face a dilemma of their own double standards. Support for the US policies determines whether the regime is acceptable. In 1991 when the Conservatives won an overwhelming vote in Algeria they were quickly overthrown and the Western powers went along happily. Not for Myanmar. Too much pressure or sanctions brings Myanmar closer to China and further erodes any Western influence to make a change.

Sajjad Ashraf served as an adjunct professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore from 2009 to 2017. He was a member of the Pakistan Foreign Service from 1973 to 2008 and served as an ambassador to several countries.