Has the US learned the lessons from Iraq war?

The deeper debate concerns use of military power as sound foreign policy tool

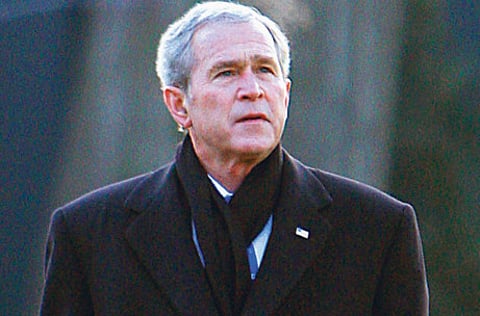

Ten years ago, when the Iraq War began, I was a producer in CNN’s Kuwait Bureau. For months leading up to that day, I had struggled to understand both — why George W. Bush and his administration seemed so determined to fight the war and why they were so convinced it would go smoothly.

The answers to those questions have filled many books over the last decade and remain the subject of intense debate. What was clear even at the time was that the terms of the discussion were badly skewed.

We in the media led earnest conversations about whether or not war would happen long after it became obvious that the White House and Pentagon had decided that question. We allowed ourselves to be distracted by arguments about what the UN inspectors were or were not finding as they moved around Iraq in the winter of 2002-03 and, in the process, ignored the clear signals the Bush administration was sending that the entire exercise was mainly about public relations, at least from the American perspective.

A decade later, there is little disagreement in the US that Iraq was a disaster of the first order: An avoidable tragedy for America and, on a vastly greater scale, for Iraq itself. To the extent that if the war still has any supporters at all, they are found on the hard right and among the neoconservative foreign policy types who once staffed the Bush administration. These figures tend to insist that the Iraq War as a whole was morally, politically and militarily sound and would have succeeded if only the planning had been more thorough and the post-invasion administration more competent. A few of them persist in portraying Iraq’s current deeply flawed, deeply sectarian government as a model for the rest of the Middle East.

To America’s credit, this is not a popular viewpoint. Indeed, even before Bush left office, it had largely been rejected. By 2007, the war’s most important advocates — secretary of defence, Donald Rumsfeld, and his deputies, Paul Wolfowitz and Douglas Feith — were out of government. Its earliest military commanders, Tommy Franks and Ricardo Sanchez, were retired as was the occupation’s civilian administrator, Paul Bremer.

Most of these men were not missed by the wider American public. When the former CIA director, George Tenet, published a memoir in 2007, his book tour became a painful exercise in black comedy as one interviewer after another browbeat the author relentlessly, verbalising an anger that Tenet himself never quite seemed to comprehend.

By that time most Americans understood, even if former senior Bush administration officials did not, that the most basic answer to the question “what went wrong in Iraq” was: First, America probably should not have been there to begin with and, second, if the US insisted on going in then there ought to have been a back-up plan. Instead, when things on the ground failed to unfold in the manner senior officials in Washington had expected, the upper levels of the American government retreated into denial and insisted that any and all criticism amounted to partisan sniping.

Looking back last week, Stuart Bowen, the soon-to-retire Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction, told the US television network MSNBC: “The United States wasn’t well-structured to carry out its mission. It shifted in the spring of 2003 from a policy of ‘liberate and leave’ to ‘occupy and rebuild’; from spending $2 billion (Dh7.35 billion) to $20 billion in the blink of an eye. Ultimately, $60 billion [was] appropriated. But there wasn’t an integrated interagency capacity to execute the programme.”

A Bush crony, whose appointment was initially viewed sceptically by many in Washington, over the last nine years, Bowen has more than proved his independence. The question going forward is whether the lessons his office has identified will be learned by a new generation of American political leaders.

At the most basic level these involve thinking through the potential consequences of one’s actions — the sort of thing that graduate students in public policy schools spend a lot of time working on, but which decision-makers in the real world often lack the time and expertise to tackle.

The deeper debate, one that has to take place both inside and outside the policy world, concerns America’s role in the world and the extent to which the projection of military power remains an effective tool of foreign policy. There are clear differences of opinion on this score, as Washington’s recent debate over the confirmation of Defence Secretary Chuck Hagel (who, as a senator, was initially an Iraq War supporter, later a high-profile sceptic) proved.

And what of those in the press? The American media have been widely, and justifiably, criticised for their gullibility in the run-up to the March 2003 invasion. Some were too ready to accept administration assurances that invading Iraq would be easy. Too few in the media asked hard questions about how, exactly, the US planned to rebuild a country that, in 2003, had been at war or under sanctions for more than two decades. Have the lessons of 2003 been learned? The current debate over military action and Iran leaves that open to question.

Facing a still-unresolved war in Afghanistan, the possibility of a future conflict with Iran and an uncertain relationship with all of the governments emerging from the Arab Spring, the question for the future is whether Washington, the American media and the public at large have learned the lessons of this lengthy and unnecessary war. The answer, for now, is that the question remains open.

Gordon Robison, a longtime Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches political science at the University of Vermont.