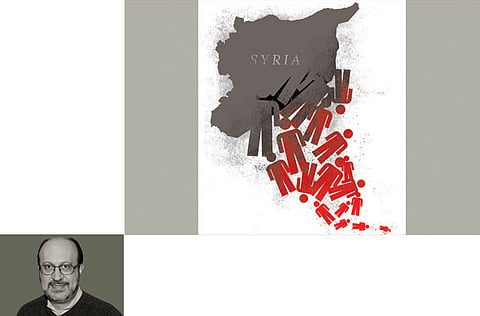

Disgraceful numbers game in Syria

Figures of those killed, refugees, wounded and prisoners are woefully wrong

Official UN figures claimed that “more than 70,000 people have been killed in Syria” since the uprising began in March 2011. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), a UK-based activist group, insisted that the total toll was much higher than the 62,554 deaths it has documented, including more than 6,000 casualties last month. Rami Abdul Rahman, the head of the group, told Reuters that SOHR believed around 120,000 people were killed during the past two years, which was higher than the UN data. Similar figures for refugees, the wounded and prisoners of war were all woefully underestimated. So what was the purpose of this numbers game?

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), a leading international institution sponsored by the Norwegian Refugee Council, 2.5 million people in Syria had lost their homes and livelihoods by November 2012. As this figure was a conservative estimate, and in the light of ongoing aerial bombardments that literally emptied major cities of their inhabitants, the five million figure — out of a total population of 21 million it was worth noting — should surprise no one. Even fewer should be astonished that several million were hungry and dehydrated, barely surviving. Another six million inside Syria needed help as well, although most lingered — caught between fear and hopelessness.

Tens of thousands have now fled the country to neighbouring Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Turkey and while the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that the number of those who actually registered jumped from 200,000 in August 2012 to 1.2 million by March 2013, the real figures were much higher. UNHCR officials acknowledged that the rate of flight from Syria did not slow down, as nearly 10,000 individuals crossed one border or another, legally or illegally, each day.

By late 2012, according to UNHCR data, the total number of Syrian refugees reached more than 408,000 in the four neighbouring countries, although President Michel Sulayman has said that Lebanon alone has hosted at least one million Syrian refugees. If Beirut opted not to follow Syria’s other neighbours in setting up official refugee camps, accommodating most with Lebanese families or providing shelter in schools or abandoned facilities, tent camps were beginning to sprout up because of a sharp rise in human flow. In Bar Elias (Biqa’ Valley), for example, there were several tent “cities”.

Unlike Lebanon, Jordan began construction of its first major camp in March 2012 and, according to the Jordanian Armed Forces, over 1,200 Syrians crossed into Jordan every day. Such a rate translated into 36,000 new residents each month, or 432,000 per year, which meant that fresh facilities were required faster than many had assumed. Still, Amman posted a modest number of 470,500 refugees, which was probably half the actual figure. In the event, Jordan finally acknowledged in early 2013 that more than 70,000 Syrians had entered the country each month that, truth be told, required the opening of a new refugee camp every 30 days.

Even Turkey, which was the first country to set up refugee camps in Hatay province in 2011, neglected accuracy. Although Ankara may now have more than 1.4 million Syrian refugees in its territory, authorities insisted that about 650,000 were registered. Bloody skirmishes between Turkish and Syrian forces along the border area have caused Turkish casualties, which forced Ankara to tighten the noose on Free Syrian Army activities, even if Turkey was the premier transit route to channel weapons to various opposition groups.

Still, by playing the numbers game, Turkey joined Syria’s neighbours in burying its head in the proverbial sand. Only Egypt (150,000), Algeria (25,000), Armenia (7,000) and Israel (7,000), posted relatively accurate figures for the number of Syrians they welcomed either on a temporary or permanent basis.

If the data on refugees was controversial, those that pertained to casualties and prisoners were even more problematic, reflecting a rare moral abyss. Few advanced exact numbers for detainees in Syrian prisons or the conditions under which Damascus held them. Suffice it to say that Muath Al Khatib, the leader of the opposition Syrian National Coalition, requested President Bashar Al Assad to release all female detainees as a goodwill gesture, when he made his dialogue offer this February. Damascus did not respond, though the Centre for Documentation of Violations in Syria, a team of activists that recorded human rights violations, provided some startling statistics: 568 women were among 35,344 total detainees in Syrian prisons in early 2013. In a 2012 report, Human Rights Watch asserted that the Baath government established 27 “detention centres,” where political prisoners were routinely tortured. Other organisations made similar or even more egregious claims.

Of course, it was critical to note that the vast majority of all casualties in Syria were civilians and though decision-makers felt sympathy and pledged financial assistance to help bordering countries provide sorely needed help, hardly any bothered with the moral abyss they confronted. Arab and western governments fell into geo-political traps, backing the false Damascus argument that foreign elements were behind the revolution or that Al Qaida, or pro-Al Qaida, forces turned the protests into a civil war. This is a disgraceful numbers game in Syria that is unbecoming and it behoves everyone to reassess how refugees, prisoners and the dead were counted.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author Legal and Political Reforms in Saudi Arabia (Routledge, 2012).