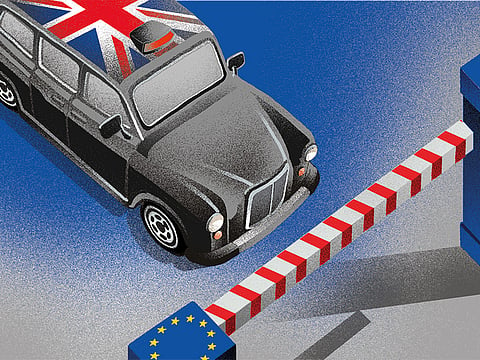

Britain has a cost to pay for Brexit

Only those closest to the negotiations can acknowledge the amount needed towards settling the huge liabilities

Nearly every negotiation comes to a crunch moment. The Brexit talks are now quite clearly coming to such a crunch, where the United Kingdom has to decide whether a major and unpalatable concession is worth making in order to secure a large number of highly desirable objectives. In this case, the potential concession involves the vexed subject of money.

To the average voter, it is readily apparent that the European Union (EU) wants Britain’s money and Britons don’t want to give it to them, but exactly why they want so much of it so adamantly must be just as obscure as why Liberals have a passion for different voting systems. Are they trying to punish Britain?

The EU certainly don’t mind Britain being in an awkward spot, but that is not the whole explanation. Is it demanding “money for access” to its markets? That would seem a bit rich when Britain would give EU states access in return. No, the main reason the EU wants a big pile of cash from the UK is because it needs it, having in effect run up a vast debt on behalf of British people and everyone else in the EU. In the obscure terminology of Brussels, this is called the RAL, the Reste a Liquider (it remains to liquidate). It is the difference between the amount the EU has committed itself to spending — on infrastructure, regional grants and so on — and the amount it has actually paid out. The polite explanation of this is that committing money years ahead but not paying it until much later allows projects — a new bridge for instance — to be planned for the future.

The less charitable way of putting it is that the EU is like a giant overbooked airline, hoping that not everyone turns up at the same time for what they have been promised. If they did they would find that the Commission is short of something like 250 billion euros (Dh1.08 trillion). It only keeps going on the basis it will never come to an end. Gaining an understanding of this is not likely to make Britons keener to stay in the EU. Indeed, people around the rest of Europe perhaps need to notice that they, like us, owe something like £400 or £500 for every man, woman and child to Brussels — it is just that Britain’s share crystallises because it is leaving. But understanding it is very important to working out what the UK should do about it, along with a similar 100 billion euros run up in pension liabilities for which no money has been set aside. It is understandable that when someone is leaving, it wants a share of these accumulated debts.

The reason this matters is because psychologically and politically it is easier to pay a debt, even if someone ran it up on your behalf, than to bow to a ransom demand. In addition, it is quite obvious that making some contribution to these amounts is an inevitable part of coming to any agreement about future trade and relations.

So, if British Prime Minister Theresa May and Britain’s Brexit Secretary David Davis declare at some point before the next European summit on December 14 that the UK will indeed pay some share of these liabilities, there is no point people responding with outrage and denouncing them for giving in to Brussels. Anyone who thinks there has ever been a chance of a free trade deal with the EU without doing this has been kidding themselves. Of course, any such payment should be dependent on a final deal being signed, sealed and ratified. Without that, the UK should not pay a single penny. That way, the UK retains some leverage right to the end. And agreeing to pay a share need not mean being committed now to a specific amount. A “share” could be calculated as the British population in the EU (12.5 per cent) or the proportion of the budget Britain pays in any one year (about 8 per cent after deducting our receipts) and since the RAL varies unpredictably, the choice of the year on which to base this calculation will be important.

British taxpayers will also expect to get back their share of the capital invested in the European Investment Bank — if Britain is paying debts it has to receive its slice of the assets as well. There are thousands of such details to haggle over. But as ever at a crunch point, there is now a key judgement to be made: Is it worth making this offer in order to unlock a deal on a transitional period for leaving the EU and talks on a full free trade area to follow?

Those who want Brexit to be a success — whether or not they favoured it — should be clear that it is worth it, because the alternative of no deal at all is deeply unattractive for everyone doing business with the continent or who wants an open Irish border.

Only those closest to the negotiations can judge the right moment to acknowledge that Britain will pay a fairly calculated amount towards these huge liabilities. They will want to know that the transition talks will quickly be on the table in return. But it will be the right thing to do, to break through to a more hopeful outlook, in a government that needs simultaneously to do the right thing and pull itself firmly together.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2017

William Hague is the former UK foreign secretary and a former leader of the Conservative Party.