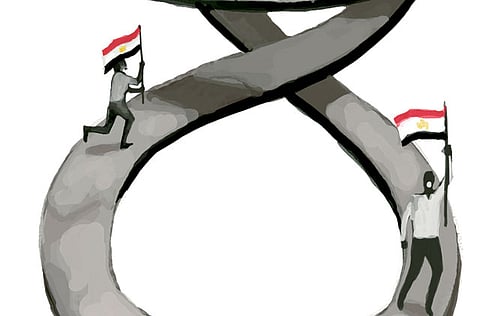

A revolution that has yet to achieve its goals

Egypt faces hurdles such as the remnants of the old regime, the presence of powerful Islamist forces and the spread of thugs

More than a year since the eruption of protests across the Arab world, countries in the region continue to endure the pangs of revolution — some further along the road to democracy than others.

Revolutions usually are brought about by angry and enthusiastic masses seeking radical changes beyond the legal and constitutional framework that prevailed before the outbreak of protests against the ruling regime. Once a revolution succeeds, a new legitimacy, called the revolutionary legitimacy, emerges to replace the previous rules and laws until a new constitution is introduced by the new authority.

Also in a post-revolution country, a revolutionary judicial body must be established in parallel with the ordinary judicial authority, to be dedicated to investigating and issuing rulings against those who oppose or plot against the revolution. This judicial authority should be headed by a leader of the revolution.

Any revolution is based on ideological visions derived from demands of the masses, which fuelled the revolution in the first place and contributed to its success. These visions should be turned into action plans and applicable programmes that meet the aspirations and ambitions of the people who revolted against the autocratic regime and sought dignity, justice and freedom.

Egypt, which recently celebrated the first anniversary of its popular revolution, passed through a previous revolutionary experiment — the 1952 revolution — led by the so-called Free Officers from the armed forces. The Free Officers’ movement managed to overthrow the monarchy, abolish the feudalist system and freed peasants and labourers, thus turning Egypt into a socialist republic.

But, the revolution swept away some inherited traditions that were manifested in social behaviours and practices, such as respect of high –class and rich people, as well as in some values related to trade, industry and agriculture.

The revolution also scraped some values that were inherited from the bourgeois class, which coincided with the presence of coloniszers in Egypt, and then replaced all these values with socialist values, which were accepted by some and rejected by some others.

The radical changes brought about by the July 23 revolution were welcomed by large sectors of the society, peasants, workers and poor classes, while feudalists and the rich rejected these changes and the socialist values that were laid down by the revolution. Egypt gained a new identity wherein workers, peasants, the poor and all the marginalised classes were given full rights and freedom and a new status.

Nowadays, Egypt’s new revolution has emerged as the main achievement of the Arab Spring, which would not have been possible without the great sacrifices of the Egyptian people and the deaths of a large number of martyrs from the middle and lower classes that were sidelined and impoverished after the 1952 revolution was emptied of its significance in the last decades of the past century and the beginning of the 21st century. This led to the emergence of a new class of bourgeoisie, which took over the country’s leadership and authority. This class, including businessmen, promoted all forms of corruption, opportunism, theft, leading the country to the verge of collapse.

This miserable situation prompted the Egyptian masses without a leader or a particular intellectual or philosophic visions to take to the streets across the country, demanding dignity, social justice and freedom.

Millions of young Egyptians and ordinary people engaged in huge mass protests that turned into a sweeping public revolution, ending 30 -years of autocratic rule.

Yet, over one year after this revolution, uncertainty still overshadows the Egyptian political scene amid the growing tensions and consecutive tragic events in Egypt. These events are a vivid illustration of major challenges facing Egypt’s quest of democracy.

In fact, Egypt faces three major and related political challenges to a successful democratic transition, the remnants of the old regime, the presence of powerful Islamist forces and the spread of thugs.

March of change

The big challenge that faces Egypt is the strong presence of the remnants of the old regime and its corrupt symbols that are still in positions that allow them to create chaos and internal conflicts to hinder the revolution. The recent deadly football riots which took place in the Mediterranean city of Port Said provided a clear proof of the involvement of the symbols of the former regime in such events as they still have the power and money that enables them to recruit thugs and outlaws to deliberately sabotage society and stand in the way of the revolution.

The sweeping victory by the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party of almost half the parliamentary seats in the free and fair elections that puts the Islamist group in the driving seat after years of repression is another challenge before Egypt’s democratic transition. The way these challenges are handled in the coming months will determine whether Egypt moves towards democracy or sinks into a new authoritarianism. The revolutionaries who spearheaded the march of change should not leave the political scene for the Muslim Brotherhood only nor should they stop their dynamic movement, because the revolution has yet to achieve its goals.

Parliamentary legitimacy does not make up for revolutionary legitimacy. Hence it is important to monitor and control the performance of the ruling authority, since absolute power is absolute evil. There are still mounting fears about counter-revolution and the hijacking of the Egyptian revolution. This poses a major threat to the democratic movement amid fears that well-organised religious parties may capitalise on the revolution and its gains, which is not in the interest of Egypt.

Dr Khalifa Rashid Al Sha’ali is an Emirati writer who specialises in legal affairs.