Damascus: Censorship rules remain extremely strict in Syria, evident by the number of titles that were knocked off shelves at the Damascus Book Fair during the first week of August. But, whatever customers cannot find at the annual book fair or at bookshops in Damascus, can certainly be spotted in street displays. The displays are chaotic, sanitation is bad — but there is no censorship.

Banned books in Syria in 2018 included all the works of Lebanese novelist Ameen Maalouf, due to his 2016 appearance on Israeli television; the memoirs of former vice-president Farouk Al Shara (because they were published in Qatar three years ago); and all history books, even those published in Syria, with the tri-colour of the flag of independence, which since 2011 has become the banner of the Syrian opposition.

Not far from the Assad National Library, where the annual fair has been held for three decades, is a small corner off Shukri Al Quwatli Boulevard. This is where a handful of book sellers have stood for nearly the same period, on the premises of a bus stop, side-by-side with sellers of second-hand T-shirts and jeans. Another bunch assembles behind the Umayyad Mosque in the Old City.

Banned books

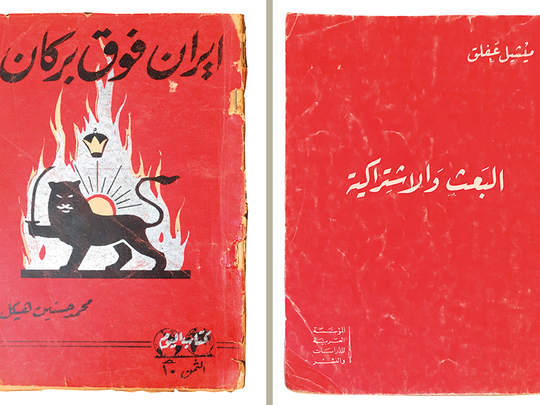

Among the piles of works, one finds plenty of banned books, like the philosophical works of Michel Aflaq, the founder of the Baath Party who was sentenced to death in 1966, and a 1970 biography of Gamal Abdul Nasser, with a forward by Lebanese Druze leader Kamal Jumblatt, who is on Damascus’s blacklist.

Also on the blacklist but still on display is an early 1950s work on the Free Officer Revolution in Egypt, authored by former President Anwar Sadat, who Damascus accuses of treason for signing a peace treaty with the Israeli regime. His books, and his autobiography, are officially banned by the Ministry of Information.

Stolen libraries

Students and university professors frequent these displays to get hold of second-hand books, always at a fraction of their original price. Bookshop owners are furious with this phenomenon, because it affects their pricing. Adel Matar, who owns a bookshop in Salhieh, told Gulf News: “Don’t go there. It’s not good to buy those books. All of them are stolen from abandoned homes.”

That is partially true, given the large amounts of belongings that were shipped out of destroyed or abandoned homes in the recent battles in the Damascus countryside. This kind of stealing, known as “ta’feesh” in Arabic, usually applies to LCDs, washing machines, and furniture, which are smuggled out of war zones on motorbikes and sold at the gates of East Ghouta. Of late, militiamen have started taking books as well, seeing that they are also in demand.

Abu Usama, who owns two book shacks, told Gulf News: “We did not steal them but bought them from those who did at Al Hajar Al Aswad and the Yarmouk camp. If we didn’t buy them, they would have been sold to cafeteria owners, where they are shredded and used to wrap shawarma and falafel sandwiches. What we are doing is neither prohibited nor haram. I paid 7,000 Syrian pounds (Dh59) for 20 rare books smuggled out Al Hajar.”

Damaged books and out-of-prints

He adds that entire libraries were also rescued from Yarmouk, with single-theme topics like Palestinian history, Damascus history, and early Islamic history. He takes out a five-volume work on the minutes of the Syrian-Egyptian Union of 1958. “In Lebanon, this costs $200. Here you can get the entire set for $22.”Damaged books cost less, he adds, taking out two out of three volumes of a dictionary on Damascene families, authored by Syrian scholar Sharif Al Sawwaf. One volume is missing, one is in bad shape, and one is clean. “These belonged to a professor at Yarmouk. I can give you the two volumes for $4.50.”

Two of Mohammad Heikal’s early works, including his first, “Iran Fawk Burkan” (1951) and “Al Okad Al Fansieh Alati Tahkum Al Sharq Alawsat” (1958) sell for $1 each. Both classics are out-of-print, even in Egypt.

English books

Riad Malki, a student at Damascus University, told Gulf News: “I sometimes find English books at a vendor named Abu Malek. They are usually cheap because nobody buys them. Most are from the homes of foreigners who left the country in 2011. The topics range from Islam, the Middle East, and the Ottoman Empire. Some are nearly 100 years old, and they sell for comically low prices.”

The seller, Abu Malek, said “I don’t sell much of these English books here, but when somebody comes from Lebanon, they buy them in dollars. Many of my customers are from the American University of Beirut.”

Autographed books

Books signed by their authors cost more than regular works, adds Abu Malek. “The more famous the author, the higher the price we can charge. The signatures of living authors cost less than deceased ones. Look at this masterpiece. It is the memoir of Damascus MP Fakhri Al Barudi, one of the heroes of Syria’s independence, signed and presented to the singer Fahd Ballan. I want $56 for it!”

Government control

When asked how these banned titles sell so freely, Abu Usama laughs: “Don’t think we are not watched or persecuted. They come after us almost daily — members of the Tourist Police who claim that we are not entitled to sell books because we make the city look bad. Books don’t look good but arms and roadblocks are okay. There are 15 of us here. We collect an amount from each and pay it regularly in bribe money to the Tourism Police, so that they leave us alone. That’s why we never give our real names to customers, fearing that they are police in disguise.”