Washington: Two months ago, the long-awaited release of the Trump administration’s ambitious plan for peace between Israelis and Palestinians — what the president has called the “ultimate deal” — seemed imminent.

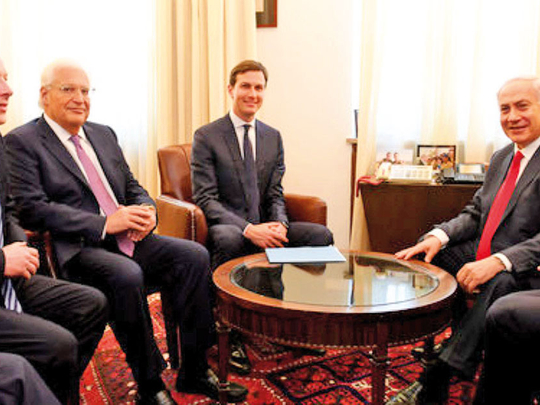

President Donald Trump’s two top envoys of the peace process — Jared Kushner, his son-in-law and adviser, and Jason Greenblatt, a former senior Trump Organisation lawyer — had prepared and begun to circulate a 40-page draft.

But the proposal hit a wall when Gulf Arab states flatly rejected terms they saw as radical, pro-Israel and out of line with traditional US policy and international law, according to officials familiar with the peace-seeking process.

Jordan and Egypt, who had similarly promising beginnings with Trump, also scotched the terms.

Failing to gain the support they expected, Kushner and Greenblatt — who both have backed right-wing Israeli causes such as the expansion of Jewish colonies on occupied Palestinian land — have moved to punish the Palestinians.

The Palestinian leadership has refused to talk to the US team since Trump decided in December to formally recognise occupied Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, upending decades of US policy.

Since then, the Trump administration has imposed new hardships on the Palestinians in an effort — so far unsuccessful — to bring them back to the negotiating table.

In the most recent example, the State Department announced on Friday that the United States will no longer contribute to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) for Palestinian refugees, calling the agency an “irredeemably flawed operation.” It criticised other countries for not doing more to help the Palestinians.

Until the Palestinians stop “bashing” the United States and agree to return to negotiations, they can expect to lose US aid, US ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley said last week at the Foundation for Defence of Democracies, a conservative think tank in Washington.

Right to return

Earlier this year, the Trump administration slashed its contribution to UNRWA, which provides schools, medical care and other assistance to five million Palestinians in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Lebanon and Jordan.

The decision announced Friday will cut off about $315 million, or about one-third of the UN agency’s total annual budget.

The Trump administration complains that the agency is vastly overcounting eligible refugees. Haley said the UN has erred by counting not just the 700,000 Arabs driven from their homes by Israel’s 1948 independence war, but also millions of their descendants.

She spurred headlines in the Middle East when she added that the “right of return,” the idea that these Palestinians could eventually return to land that is now part of Israel, must be re-examined.

Though the refugee issue is a fundamental cause of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, most experts agree a “right of return” has become more abstract than a real possibility. Still, successive US administrations declined to jettison it altogether. Instead, they have argued for compensation and some land swaps with Israel.

Those controversial ideas form the basis for the 40-page document drafted by Kushner and Greenblatt, said current and former US, Israeli regime and Palestinian officials and diplomats briefed on the peace plan or familiar with it, and spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss its contents.

“The US drive to change the long-established principles of a deal have been more than music” to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, said Nimrod Novick, former adviser to the late Israeli prime minister and peacemaker Shimon Peres.

“I suspect he has been the driving force behind it: Take [occupied] Jerusalem off the table, then take refugees off too,” said Novick, a fellow at the New York-based Israel Policy Forum, which advocates for Israeli and Palestinian states coexisting side by side. “All before we change attitudes on security and eventually on borders as well.”

Kushner, 37, has said he was uninterested in the history or background of the generations-old and seemingly intractable Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

But diplomats, experts and even the Israeli military caution that siding so heavily with Israel, and taking from Palestinians any hope for eventual independence, could lead to more violence in the region.

David D. Pearce, who served as US consul general in Jerusalem in the George W. Bush administration, warned, “It will not create diplomatic leverage to take away funding for schools and health services,” he said on Twitter. “It will create hatred.”

Another force behind the controversial moves is David Friedman, the US ambassador to the Israeli regime and Trump’s former bankruptcy lawyer. He also supports right-wing Israeli causes.

In addition to pushing successfully for the transfer of the US Embassy from Tel Aviv to occupied Jerusalem, Friedman has persuaded the administration to drop the universally used terminology of “occupied territories” when referring to the West Bank and Gaza.

The administration “sees this as an opportunity to realign American policy in a way not seen in 25 years,” said veteran Mideast negotiator Aaron David Miller, “and to make it more difficult for successive administrations to reset.”

— Los Angeles Times