EAST ORANGE, New Jersey: Marla L. Andrews put on her glasses, held the small plastic bag close and strained to see the gold ring inside.

Her vision is poor, and the opaque bag made it impossible for her to see the inscription on the inner surface of the ring: “P.D.,” a heart with an arrow through it, and “L.E.D. 5-31-43.”

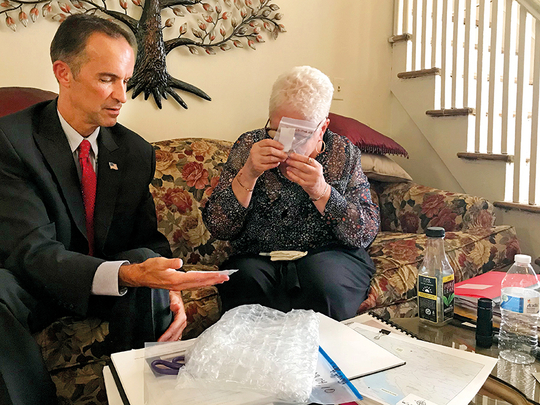

Thursday afternoon, Andrews, 76, sat in her living room here and struggled to make out the artefact that had just become a piece of her history, and that of the United States.

Last month, the Defence Department announced that it had accounted for Dickson, among more than two dozen black aviators known as Tuskegee Airmen who were still missing from World War II.

Dickson, who had trained at the Tuskegee Army Flying School, was 24 when he crashed in mountainous southern Austria on December 23, 1944, while on an escort mission.

Seventy-three years later, his ring was found in the dirt by a University of New Orleans graduate student, Titus Firmin, during a dig last summer at the crash site near Hohenthurn.

Charred remains and other small personal items were also found, along with parts of the aeroplane.

On Thursday, Michael Mee, the identifications chief for the Army’s Past Conflict Repatriations Branch, presented Andrews with the ring and a formal report on how her father was accounted for.

Andrews sat in a black skirt and coloured blouse, wearing gold hoop earrings and holding a tissue and a black marker.

The 14-karat Art Deco ring was a prize, the physical link to a man Andrews barely knew, and to a different life that might have been, had he come home.

There had been talk for months that a ring had been found during the dig. Now, here it was, encased in bubble wrap, inside a larger plastic bag that Mee pulled from his black briefcase.

“This is the ring,” he said.

“Wow, guys,” she said quietly.

“Want me to take it out for you?” Mee asked, referring to the plastic bag.

“No,” she said.

(She said later she didn’t want to remove it because she wasn’t ready.)

The excavation had also found the ring’s aqua-coloured stone, which had broken loose and was in a separate bag. Andrews said her mother had loved the colour aqua, and she guessed that her mother had bought the ring for her father’s birthday.

Mee also turned over a small remnant of a harmonica that was found at the crash site, and a small cross.

Capt Dickson had loved music. He had taught himself to play the guitar and had taken an electric guitar with him when he went overseas. It was never returned to his family after his death, according to his records.

Mee, who was accompanied by Army Maj Phillip Richardson, explained how the scientific identification was made.

DNA had been extracted from arm and leg bone fragments found at the crash site and matched with DNA from Andrews, a nephew and a distant cousin the Army had found but whom Andrews had never heard of.

The report contained pictures of the pieces of Capt Dickson’s ribs, hands, spine, arms and legs recovered from the site. “Highly fragmented, small quantity of remains,” Mee said.

Andrews, who sat on a floral-patterned couch, looked sombre when Mee explained that some of her father’s bone fragments were charred from the plane’s crash.

These were “perimortem” injuries, which happened at or near the time of death, he said.

“Some of the remains are blackened,” Mee told her. “There was a fire. The aircraft caught fire ... This is very typical of an aircraft accident.”

Capt Dickson, of the 100th Fighter Squadron, was among the more than 900 black pilots who were trained at the segregated Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama during the war.

They were African-American men from all over the country who fought racism and oppression at home and enemy pilots and anti-aircraft gunners overseas.

More than 400 served in combat, flying patrol and strafing missions, and escorting bombers from bases in North Africa and Italy. The tail sections of their fighter planes were painted a distinctive red.

The dig was conducted by the Defence POW/MIA Accounting Agency, the University of New Orleans, and the University of Austria at Innsbruck, with help from the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

There are 26 Tuskegee Airmen still missing from the war.

Lawrence Dickson had married Phyllis Constance Maillard in November 1941. (She remarried and died on December 28, 2017, in Nevada at the age of 96.) The couple lived in New York City. Marla was born July 14, 1942, in Harlem’s old Sydenham Hospital.

Two days before Christmas 1944, Dickson took off from his base in Italy, in a P-51D Mustang nicknamed “Peggin,” headed for Nazi-occupied Prague.

He was on his 68th mission and had already been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for meritorious service.

He was leading a three-Mustang escort of a fast but unarmed photo reconnaissance plane, according to the account of a wingman, 2nd Lt Robert L. Martin, many years later.

(Martin died on July 26 at the age of 99 at his home in Olympia Fields, Illinois.)

The four planes headed over the mountains for Prague. About an hour into the trip, Dickson radioed that he was having engine trouble and began losing speed.

His wingmen stayed with him as he dropped back. The twin-engined reconnaissance plane sped on and was soon out of sight.

Dickson decided to turn for home in his crippled plane, and his buddies stuck with him.

He looked for a spot to land or bail out. Martin saw him jettison the canopy of his cockpit before bailing out, but then he lost sight of the aeroplane.

The two wingmen circled, looking for a parachute, a column of smoke or burning wreckage. There was nothing but an empty, snow-covered valley.

After the war, the Army searched for Dickson in northern Italy, where Martin thought he went down. Other crashed planes and remains were found, but not his.

In 1949, the Army recommended that his remains be declared “nonrecoverable.”

Last August, Andrews got a phone call at her home from the Past Conflict Repatriations Branch, saying experts, armed with new data on the crash location, were investigating her father’s case anew.

On Thursday, Mee said the captain’s remains, now in a laboratory in Nebraska, would be placed in a coffin, and wrapped in a traditional Army blanket fastened with a large safety pin.

Andrews said she would like her father to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Mee said it might be possible for the modern 100th Fighter Squadron, with the tails of its jets painted red, to make a flyover at the funeral.