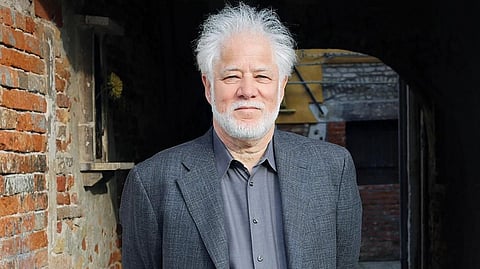

Michael Ondaatje talks about his latest book, Warlight

Michael Ondaatje’s latest tale – of children cast into a world of intrigue – echoes his own life

The title of Michael Ondaatje’s new novel, Warlight, which is set in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, refers to the gloaming that enveloped London by night during the blitz. But it might equally describe the fragile, haunting, almost whispered quality of Ondaatje’s writing – “the way’’, as he once put it, “when someone speaks very quietly, you move forward so you can listen more carefully.” So finely constructed are his sentences that you find yourself holding your breath lest you inadvertently disturb their symmetry.

Speaking on the telephone from New York, Ondaatje says his novels tend to begin with “just a tentative glance at something”, the glance in this case being the very first sentence of the book: “In 1945 our parents went away and left us in the care of two men who may have been criminals.”

‘It had an element of one of those dark fairy tale openings,’ he says with a laugh. ‘Things are going to go wrong...’

The narrator is Nathaniel, whose parents have left him and his sister Rachel in their London home after telling them that their father has taken a job in Singapore. In their place come Walter, whom the children christen “the Moth” - a mysterious presence, who flitters in and out of the home; and a man known as “the Darter”, a former boxer now engaged in the “jubilantly illegal profession” of greyhound racing, smuggling from Europe dogs of questionable health and pedigree for rigged races.

Gradually, it emerges that Nathaniel’s mother has not left for Singapore at all, but is engaged in intelligence work, in the “unauthorised and still violent war” that persists in various parts of Europe, and in which the Moth and the Darter have played, or continue to play, some part.

Inexorably, the two children are drawn into the intrigue, Nathaniel accompanying the Darter on his dog-smuggling operations and eventually becoming involved in intelligence work himself, while Rachel, more palpably damaged by her parents’ desertion, retreats into her own private anguish. Warlight is simultaneously a boy’s journey to manhood, a romance, and a spy thriller – a peculiarly English tradition that Ondaatje says he has always enjoyed, from Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands, to John le Carre – set in that liminal time of “war ghosts and grey unlit buildings”.

‘It’s a very precarious time, from war to peace – or peace to war – because everything is uncertain,’ Ondaatje says. ‘Families are reunited after being separated for a number of years, all that sort of stuff happens, and the awkwardness of that became interesting to me.’

Warlight follows a similar path to Ondaatje’s earlier books The English Patient and Anil’s Ghost (his 2000 novel about the civil war in Sri Lanka) in examining the effect of conflict on what the author calls “people on the periphery”. But, for Ondaatje, the new book is “not really a war novel”, more a ‘kind of reflection of the war from the point of view of people who in some odd way have been damaged by it.’

It is a narrative that echoes Ondaatje’s own life. He was born in Sri Lanka in 1943. His father, a tea-planter, was a chronic alcoholic; his parents separated when Ondaatje was a small child, and he was raised by a series of aunts and grandparents. Then, at the age of 11, he was put on a boat to travel, alone, to England, to join his mother, brother and sister.

The school in question was Dulwich College, also the alma mater of Raymond Chandler and P G Wodehouse, to where, “perversely” he elects to send Nathaniel, where he is “beaten by a prefect, who could not stop laughing”. Shades of autobiography there, perhaps? Ondaatje will be talking at the college as part of his forthcoming book tour. ‘I’m going into enemy territory,” he jokes.

At the age of 18, he left Britain for Canada, to join his elder brother Christopher, a publisher and philanthropist, and to attend university in Quebec, where he first started writing poetry for small literary magazines, going on to publish 13 books of his verse over the years. His first novel, The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, a meditation on the life of the outlaw which shifted between poetry and prose, was published in 1970. Warlight is only his eighth novel in 48 years. Ondaatje would be the first to admit that he is hardly prolific, but then that’s what comes from treating novels like poems, ‘in the sense,’ as he puts it, ‘that every words counts.’

He rewrites obsessively, up to 25 drafts, the first five by hand using a fountain pen, ‘so there’s a lot of scratching out and big arrows going back to page 25, that kind of thing.’ His painstaking deliberation ‘drives everyone crazy’, because of which he never commits in advance to a specific deadline when working on a book. ‘There’s a well-known saying in Sri Lanka, that if you’re travelling to a town called Kataragama, it’s very bad luck to say when you’re going to get there,’ he says. ‘I think a book is a bit like that. You set off – you work and work and work, but you’re never sure when you’ll arrive – or even where you’re actually going.’

A vivid sense of place is central to all of Ondaatje’s novels, and in Warlight, London itself is as much a character as any in the book. He likes to engage in reconnaissance; it was wandering around Putney that he happened upon the quiet side street of Edwardian houses where Nathaniel and Rachel live, and where a strange assortment of semi-criminal visitors gather.

Also read: Soon humans will be able to live 1,000 years

‘I was going up and down the street for about half an hour taking photographs,’ says Ondaatje. ‘People were looking out of their windows thinking I was a future robber.’

Nathaniel’s furtive travels with the Darter take him by barge along the Thames and into the network of canals connecting the city to the wartime munitions factory of Waltham Abbey. Ondaatje spent several days exploring the area, writing a lyrical scene where Nathaniel’s girlfriend Agnes dives into the water at Newton’s Pond, before discovering that it was here that scientists worked on developing torpex, a key explosive in Sir Barnes Wallis’s bouncing bomb. ‘We all grew up with the Dambusters, and I was thinking, ‘‘My God, this place is where they were testing explosions underwater!’” It is the sort of discovery, Ondaatje says, that “doubles the story in a way”.

‘God knows what I would do if I wasn’t a writer,’ he adds. ‘I just love the craft of making a book. And what’s exciting about writing a book where you don’t know where it’s going to go is that you discover remarkable things that point the direction for you.’