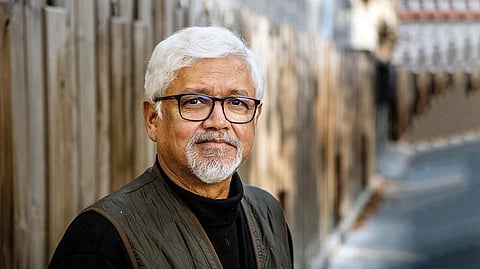

Amitav Ghosh: ‘Young people understand climate crisis in a way my generation has failed to’

Jnanpith award-winning author Amitav Ghosh, who will be speaking today at the Sharjah International Book Fair, tells Anand Raj OK how a spice spelt doom for an island and its culture, why he is not optimistic about climate summits and what keeps him hopeful

Last updated:

8 MIN READ

The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis

The Nutmeg’s Curse

Friday

The Circle of Reason

The Calcutta Chromosome

The Nutmeg’s Curse

Jungle Nama

The Hungry Tide

Jungle Nama

Jungle Nama

The Hungry Tide

The Nutmeg’s Curse

Amitav Ghosh will be speaking at Sharjah International Book fair today (Friday, November 12) at the Intellectual Hall at 8.30pm.

Get Updates on Topics You Choose

Up Next