Journey across the pacific

Chia-Chia Lin’s debut novel revisits a tragedy in an Asian-American immigrant family

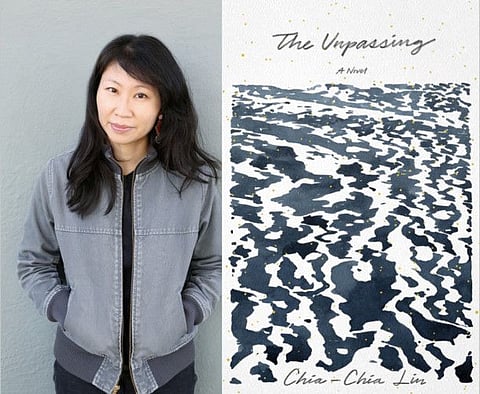

The Unpassing

By Chia-Chia Lin, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 278 pages, $26

Throughout Chia-Chia Lin’s sombre debut novel, about the muffled anguish of a Taiwanese-immigrant family struggling to adapt to the Alaskan wilderness amid the recent death of their youngest child, questions of home persist. A theme so timeless as to suggest a certain stolid permanence, this vagueness of home inspires even as it eludes members of a single household, creating a familiar world within an unfamiliar land, a country that is simultaneously everywhere and nowhere. The challenge for the narrator (and, to a certain extent, the reader) becomes how to reconcile the static “unpassing” of memories and identities, despite the exposure of time.

Set within a Lorelei-like rural landscape 30 miles outside Anchorage in the 1980s, “The Unpassing” is narrated by the Taiwanese-born Gavin, whose family brought him to this peripheral expanse of America on the edge of the Pacific when he was 3. Trawling through a vast ocean of memories years later, Gavin revisits the period when, at 10 years old, he contracted meningitis, fell into a coma and was hospitalised. Once recovered, he learned of his little sister’s fate — she was infected, too, but did not survive. The tragedy inevitably magnifies unspoken tensions in the already struggling immigrant family, which are heightened further when subpar work by Gavin’s plumber father (he was an engineer in Taiwan) results in the fatal poisoning of a young boy.

Gavin’s search for a lost geographical and spiritual centre underscores his longing for an idealised past from the fragmented present. Peering from the forbidding Alaskan wilderness just beyond the cultivated security of his family’s yard at one point, he says: “In the woods, it was darker and stiller, and I streaked through it all. I wasn’t heading home, though I suppose I was. There was always just this one path, headed one way. I had no choice, really; I was always headed home.” Later, when his younger brother loses his way in the forest during an especially stormy evening, Gavin explains: “The truth was, we didn’t know the woods at all. We only knew the path. Once you stepped off of it, there was no telling what you’d find.”

As Susan Sontag has written, “to remember is to voice — to cast memories into language — and is, always, a form of address.” This raises an obvious question: To whom is Lin’s deracinated narrator addressing his homesick telling and retelling of his family’s history? Strikingly, the only character who remains unnamed throughout the novel is Gavin’s mother, who represents both his origin and the implied endpoint of his trip down memory lane. Although discomfiting and unreliable, memories promise comfort and self-discovery, and it is hardly coincidental that an adult Gavin returns to his birthplace in search of home: “I went to Taiwan, trying to find the village that lived in my memory of my mother’s memory.” But he comes to realise his relationship to the place is ambiguous, both distinctly of it and separate from it. It is a hard-won, elegiac truth about an unsalvageable past, this Sebaldian secondhand memory, the eventual recognition that he cannot step into the same river twice, which he presages at the very beginning of his narrative: “Although we tried, each in our own way, no one was able to go back even one step.” Wisdom in hindsight is, after all, one of maturity’s age-old graces.

If the novel seems unrelentingly cheerless at times, its tone reflects Gavin’s struggle to come to terms with his family’s particular history of displacement and loss. Immigrants, just like Joseph Brodsky’s exiled writers, are often “retrospective and retroactive beings.” Nevertheless, Gavin’s articulation of his family’s circumstances bears the inexorable imprint of an American collective memory that is variously functional and symbolic. Punctuating his thoughts are neither contemporary Taiwanese nor Asian cultural references, but rather the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion, Time magazine and the Exxon Valdez oil spill off the Alaskan coast. His mottled identity creates familial strains: Disappointed with his visit to Taiwan, Gavin remonstrates: “It was a kind of violence, what my father had done. He had brought us to a place we didn’t belong, and taken us from a place we did. Now we yearned for all places and found peace in none.”

For all of its pathos, its themes of cross-cultural intermingling, its stories of immigrant arrival, marginalization and eventual accommodation, “The Unpassing” is a singularly vast and captivating novel, beautifully written in free-flowing prose that quietly disarms with its intermittent moments of poetic idiosyncrasy. But what makes Lin’s novel such an important book is the extent to which it probes America’s mythmaking about itself, which can just as easily unmake as it can uplift. Before he revisits Taiwan, Gavin heads back to his Alaskan house — his father’s old dream. “My father fancied himself some kind of pioneer,” he reflects, but “the expanse made him totally unfettered. The distance stripped his words. There was no self-consciousness, only sentiment.” If the United States is merely an idea that it forms of itself, then let the nostalgic among us be warned: We may be longing to return to a time that no longer exists — or perhaps never did.

–New York Times News Service