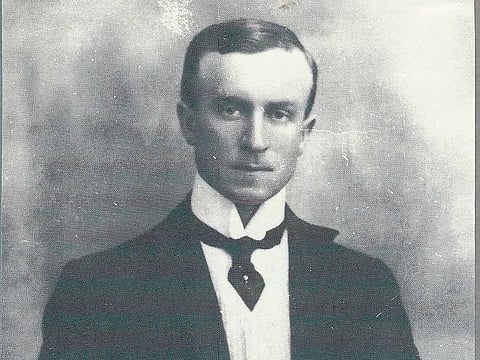

John Buchan, a man of no mystery

A biography by author’s granddaughter, Ursula Buchan, reveals truth duller than fiction

Ursula Buchan, Bloomsbury, 512 pages, £25

Real lives have a story, but no plot. In retrospect one may discern a shape, but they have no pattern or orchestration. They are, from an artistic point of view, quite unsatisfying, which is why fiction was invented.

John Buchan (1875-1940) led a full life, blessed with friends and family, decorated with all sorts of honours and achievements. There was action in it, but not much drama, and that want may have inspired his stories of derring-do, of spies and adventurers and innocent men wronged. Like many writers, he lived his best and most fulfilling life in his head, among his characters; his actual life could not compete with it.

Ursula Buchan, his granddaughter, has made efforts to animate this new biography of “JB”, as he was known, has read the work with impeccable care (more than 100 books) and traipsed in his far-flung steps around the colonies (South Africa, Canada) where he pursued an administrative career.

She has paid him a due that would make her illustrious forebear proud — a labour of love. Sadly, that equation works out mostly to the reader’s disadvantage: her love, our labour. The best parts of it are those years when the young JB was finding his feet, and his voice. A son of the manse, he was raised in a loving atmosphere by a cheerful Free Church of Scotland minister and a mother whose neediness and ambition would never let him be.

Bright but shy, JB was both a sportsman — he loved golf, hiking, fishing, mountaineering — and a bookman, earning money from novels and reviews even when an undergraduate at Oxford. He enjoyed the hijinks of student life, once saving an American friend who passed out with shock after a Roman candle was put down his “Oxford bags”.

Buchan got a first, studied for the bar and then went out to South Africa tasked with reconstruction of the Boer republics, an unhappy experience that exposed him to the dark side of British colonialism.

Back in London, he hobnobbed with influential types and in marrying Susan Grosvenor, a bookish girl from a notable aristocratic family, revealed a mild inclination for mountaineering in the social heights.

As Ursula Buchan puts it, his marriage introduced him to a large network of “agreeable connections”, though he still earned all the money.

In August 1914, the month Britain entered the war, JB began writing The Thirty-Nine Steps while on holiday with his family in Broadstairs. When published in October 1915, it was a hit, not least among soldiers at the front: “It is just the kind of fiction for here,” one officer wrote to him. It is thought that editions still bearing a dustjacket are rare because most of them were lost in the mud of France.

The book Buchan nonchalantly dismissed as a “shocker” changed his fortunes, and Hitchcock’s 1935 film — a racier affair — cemented it in the public imagination for good.

Richard Hannay, the story’s hero, became a byword for pluck and resourcefulness under pressure. Buchan’s own war involved organising propaganda as director of information at the War Office (his younger brother, Alastair, was killed at Arras in 1917), a bureaucratic role that would characterise the remainder of his life.

The biography becomes thereafter the record of a desk job, as an MP and later as governor-general of Canada. He carried out these offices with unswerving diligence and loyalty — admirable qualities, and guaranteed to kill all known traces of narrative excitement. In a life apparently unshadowed by scandal or dishonour, what might have lent the book a dash of vinegar was some deep-lying flaw in JB’s character.

But aside from a slight case of vanity (after the war he petitioned the colonial office for an honour and was turned down — by Winston Churchill), the man was more or less a paragon. His biographer has not stinted in ferreting out every wonderful thing ever said about him. “What a joy was his conversation,” recalled Stanley Baldwin, who also went on to praise his enthusiasm, humanity and profound learning.

Douglas Fairbanks Jr thought him “one of the greatest men of our day”. He was devout, hardworking, selfless, brave in the face of longstanding illnesses, and as well as showing immense kindness and patience he helped out friends and family with money. He was a keen supporter of women’s suffrage, even if his portrayal of them in fiction was generally feeble and on occasion ridiculous.

The strange thing about Ursula Buchan’s eulogising is that I believed most of it — he probably was as delightful as she claims. But praise heaped as unsparingly as this blots out nuance and chokes off interest. Great men may be a privilege to know, but without redeeming vices they are very dull to read about.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd