In America, ‘misogyny is alive and well’

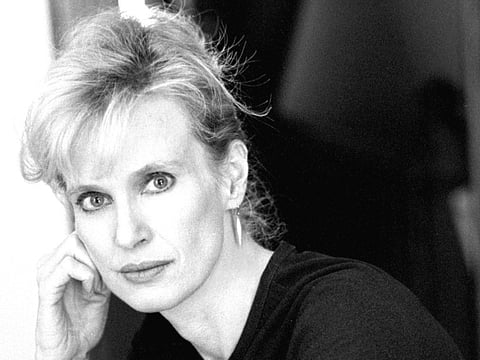

Author Siri Hustvedt talks about feminism, the arts-science divide and female intellectuals

Speaking to Siri Hustvedt in her Brooklyn brownstone not long before the American presidential election, conversation naturally turns to Hillary Clinton. “For someone so accomplished ... who performs as superbly as Hillary Clinton does, to be constantly criticised,” Hustvedt muses. “When she performs brilliantly in a debate, they call her over-rehearsed. I have never heard anything like that said about a man.”

Hustvedt knows something about being an accomplished woman, and having things said about her work that would never be said about a man’s. I am here to talk about her new book of essays, “A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women”. One of them, “No Competition”, catalogues her experiences as “a woman writer married to a man writer [Paul Auster]”. A journalist insists that Auster must have taught her psychoanalysis and neuroscience. A publisher magnanimously instructs her to “keep writing” when she has already published three novels. A fan asks if her husband has written sections of her most recent novel, “The Blazing World”.

During my meeting with Hustvedt, Auster is just a low murmur moving around elsewhere in the house. “He is doing an interview upstairs,” Hustvedt explains. “I think for the first time in our history of 35 years together, we have books coming out one month apart.” We don’t mention him again.

Hustvedt says she often encounters surprise that she is, above all, a person interested in ideas. “Women who write books about ideas are not instantly anointed in the way that men are. You get a lot of criticism for being too intellectual, too cerebral. But I don’t see those same complaints addressed to male writers. I’m sure they’re out there, but not to the same degree.”

“A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women” seems likely to inspire more people to call Hustvedt “cerebral”, though in this context as a compliment. Somewhat unusually in a publishing age characterised by slim essay collections about personal experience, Hustvedt’s book is nearly 600 pages of learned commentary on everything from the nature of literature to neuroscience. It takes in a remark Karl Ove Knausgaard once made to her — women writers, he said, were “no competition” — as well as the work of the 17th-century philosopher Margaret Cavendish. The centrepiece is a 200-page meditation on “The Delusions of Certainty” that ranges from the science of perception to neo-Cartesianism to the history of psychiatry.

Hustvedt has never been a writer of narrow or fleeting interests. “These are questions I have been addressing in both my fiction and nonfiction for a very long time,” she says. “It’s about a long, long accumulation of knowledge, and changing my mind, rethinking, discovering another beat I hadn’t been thinking about before. Or discovering some earlier thought that’s wrong.”

It should be said that this is also a pretty good description of Hustvedt’s conversational style. She makes a statement, then revises it, and revises it again. It’s not that she is uncertain of what she thinks; it’s that she’s precise.

Hustvedt was born in Minnesota, in 1955, to a Norwegian mother and an American father of Norwegian descent. As a child, she spent time in Norway, and graduated with a degree there in her teens. (For days after our interview I find myself trying to emulate her correct pronunciation of the name “Knausgaard” — something like “K-NOOSE-gurt”). She says she became a feminist at 14, “carrying around my ‘Sisterhood Is Powerful’ and Kate Millett, and trying to read Simone de Beauvoir and it was that terrible edition [of ‘The Second Sex’] translated by the zoologist [Howard M. Parshley]”.

In the 1980s Hustvedt had her poetry published and got a PhD in English literature from Columbia, writing her dissertation on Dickens. She then published several novels, each to greater acclaim than the last. But the differential treatment she received as a writer and thinker who also happened to be a woman became an abiding theme in her work, too. In “The Blazing World”, the main character is a female artist whose work is largely neglected in her lifetime, while her husband, an art dealer, is relatively successful. “In that effete microcosm,” writes Hustvedt, “it is fair to say Felix had been a giant, dealer to the stars, and I, Gargantua’s artist wife.”

The resurrection of female intellectuals from obscurity is a preoccupation of Hustvedt’s. At one point she begins to quiz me about the mathematician Emmy Noether. “She did work in symmetry in mathematics that then became adopted in physics,” she tells me. “Extremely important thinker. Praised by Einstein. Praised by, I think, Heisenberg. The stellar figures of 20th-century physics thought Noether was a genius. Does Noether set off bells in your head? No?”

“The Blazing World” was generally well received, but there were “quite a few reviews that said, ‘But she’s not likable’. Well neither is Raskolnikov,” Hustvedt says. “This [criticism] is so much more aimed at a woman’s book than a man’s book. Where did that come from? What kind of a criterion is that for a work of literature?”

Not that she is fond of hard definitions of literature. In another essay she alludes to James Wood, particularly his book “How Fiction Works”, with dismay and disdain. “It’s incomprehensible to me that anyone who has read a great many books could come to any conclusion about how books should be written.” She talks about telling a prize committee that in the whole history of literature there has never been one clear formula for what makes a good book. “Goya said ‘There are no rules in painting.’ And I think there are no rules.”

Certainly Hustvedt has not been observing any rules herself. As well as writing she has a burgeoning career as a thinker in psychiatry and neuroscience. Her longstanding interest in those subjects took off after the success of “The Shaking Woman”, a hybrid memoir and intellectual investigation she published in 2009. The departure point was her own illness — a nervous disorder that caused her body to convulse and gave her migraines — but it quickly expanded into an inquiry into the nature of the self that encompassed both contemporary research and the work of Jean-Martin Charcot, a 19th-century neurologist who studied hysteria.

This sideline in science has been transformative. “You can sit and argue about whether or not you like a writer deep into the night, and you can make arguments about why, and at the same time it’s not like finding the fault line in somebody’s argument about the predictive brain.” The problem is that science tends to appeal to a limited audience. “People who are working in neuroscience, they can see what’s original. People outside of those worlds, they don’t know where I’m original. Where I’m shocking people. They can’t see.”

For Hustvedt the gulf between science and the humanities is something of a tragedy. In the introduction to “A Woman Looking at Men...”, she laments that “I have witnessed scenes of mutual incomprehension or, worse, out-and-out hostility.” She devoted her work in the sciences to drawing connections between what you could call humanistic ideas and scientific findings. She thinks that gender bias could be explained by way of the science of perception. “The brain as an organ of prediction is founded on prior expectations,” she explains. And our prior expectations are often set up to disadvantage women: we don’t associate them with artistic greatness.

The connections between body and mind fascinate her, too. For example, lately Hustvedt has become “very interested in the placenta”. It has only been lightly studied, even though scientists refer to it as a kind of “third brain” in the process of human development, but Hustvedt’s interest is also philosophical. “What does that literal mediator, that is the beginning of every human being, have to do with our later development? The idea of mediation is there in utero as an actual physical organ. This has to have an effect on what we become.”

Some of this abstracted talk may sound alienating, but in person Hustvedt’s engagement has an infectious quality. It reminds me of something she wrote about another apparently intimidating writer, Susan Sontag. “In every conversation I had with her I found myself amazed at the certitude of her opinions,” Hustvedt writes. In conversations with Hustvedt, the observation is slightly different: it’s hard not to be amazed at the richness, the texture of her views. “I’m always doing this tug of war between different positions. It’s not that I don’t have a position. But I really do not have a final position on a great many profound questions,” she says, later adding, “I am alarmed by all kinds of solidified knowledge.”

In the weeks after our interview, one particular piece of knowledge did firm up: Hillary Clinton would not be the president of the United States; Donald Trump would be. Hustvedt had repeatedly told me that the election was “charged with misogyny”. So how does she feel about things now?

“He was elected because his exploitation of the big lie technique worked, because misogyny is alive and well among women and men,” she says. “He was elected because, as a study at Yale demonstrated, when faced with an identical description of an ambitious politician, both men and women respond to a female candidate with feelings of ‘moral outrage’, but have no such feelings for a power-seeking male candidate.”

It goes back to what she has been saying about the science of perception, the kinds of expectations we have for men versus those for women. “If she’s emotional, then she’s like a woman. If she’s not emotional, then she’s cold and heartless,” she says of Clinton. “Whereas Trump actually has played the female role: the out of control, angry hysteric. And yet, he has been perceived as a robust, masculine figure by a large portion of the US public. The possibilities for a woman are infinitely more narrow.”

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

“A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women: Essays on Art, Sex and The Mind” by Siri Hustvedt is published by Sceptre (£20).