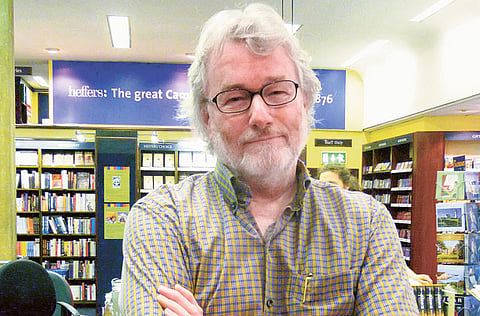

British writer Iain Banks does not mince words

Iain Banks offers his means of protesting against the atrocities of Britain and Israel

Iain Banks isn't exactly known to shy away from expressing his political views. After all, this is the man who, in protest over the Iraq war, notoriously cut up his British passport and sent the remnants to 10 Downing Street. In 2004 he signed a petition to have then prime minister Tony Blair impeached for taking the country to an illegal war.

After Israel's attack on the Mavi Marmara, the Scottish writer instructed his publisher to turn down any book translation deals with Israeli publishers. In a letter to The Guardian, Banks invited others to join the boycott: "I would urge all writers, artists and others in the creative arts, along with those academics engaging in joint educational projects with Israeli institutions to consider doing everything they can to convince Israel of its moral degradation and ethical isolation, preferably by having nothing more to do with this outlaw state."

But his political activism hasn't just been limited to troubles in the Middle East. Banks, who was chosen by The Times as one of the "50 greatest British Writers" since 1945, is also a signatory to the Declaration of Calton Hill, which calls for Scotland to get independence.

Born in 1954 in Fife, Scotland, he had wanted to be a writer since his primary school days. Banks studied English literature, philosophy and psychology at Stirling University and, after years of facing rejection letters for his novels, finally gained recognition with the publication in 1984 of his now-classic work The Wasp Factory. He has since written prolifically in mainstream fiction and science fiction and is one of those authors to have excelled in both genres. His new book, Surface Detail, is the latest in his acclaimed long-running science fiction series of the Culture novels.

Weekend Review met Banks during his trip to Cambridge, where he had come for a book-signing. The man described as "the most imaginative British novelist of his generation" talks about why he is calling for an intellectual boycott of Israel, the "horrible" thing he would like to do with Tony Blair's autobiography and support for an independent Scotland.

Where does the title of your new book ‘Surface Detail' come from?

Well, one of the main characters got a very intense tattoo over her body and inside her body as well, in her bones and major organs. So everything has got a pattern to it. I think that was sort of the main idea in the way the stuff is detailed all over her body. I am not sure that really completely comes off but that is the title I stuck with. I couldn't think of a better one, so that is what I went with.

This book is part of a series. If someone hasn't read the previous ones, could they read ‘Surface Detail' as a stand-alone novel?

They are all meant to be stand-alone but the only trouble with that is by now, I am sort of so ‘Cultured'. The series is so ingrained in me. I know so much about it — not all of which I have put in the books. But the thing is that I know so much about the books, there is always the danger that the books which I think are stand-alone might not be so comprehensible to somebody who hasn't read the earlier ones. Hopefully they still are. But I would probably advise people to either start right from the beginning, with Consider Phlebus, the first of the Culture novels to get published, or maybe The Player of Games, because it is in some ways the least science fictional of the Culture novels.

You write under two names (Iain Banks for mainstream fictional writing and Iain M. Banks for science fiction). Does it create confusion for you?

Not for me. I think it creates confusion for other people. I am very clear about it.

I mean, I don't write for nine months of the year. I only write for two to three months in a given year. I plan a lot. But once I start actually writing, it's not as if I finish a science fiction book on Friday and start on a mainstream book on Monday. It doesn't work that way. So there are months and months when I don't do any writing at all. So I have forgotten about the last book by the time I have come to the next one. So there is no sort of confusion from that.

I find your political views very interesting. You tore up your British passport over the Iraq war. Did you regret it afterwards?

Oh no. I wish I could have done more. It was symbolic, actually, more than anything else. I felt ashamed to be British. I didn't want to go abroad and have foreigners expecting me to support what was being done — this immoral, illegal, unnecessary war. And also, I felt so angry that it was that or do something worse. I had a big old Land Rover at the time. I was seriously thinking about driving it through the gates of a local nuclear dockyard. But I'd just get sub-machined to death by the guards there.

So it was a way for me to get that sort of anger and frustration in a symbolic kind of way. It did no good, of course. I just think you have a responsibility to try and express your fury at what's been done, you know, in a supposedly democratic country. I have got the passport back now. By the time Bush and Blair have both left office.

You have read Tony Blair's autobiography, then?

Oh, I have nothing to do with that! Wouldn't read it. If I got a free copy, I would just ... I have got a collection of horrible books. I have got Dianetics by L. Ron Hubbard that has been shot by I think three or four rounds [of bullets.] I have got a copy of a Gor book by a writer called John Norman. That has been set in concrete. This has all been done by Edinburgh University Science Fiction & Fantasy Society. They always have a poll for the most-hated books each year.

My then wife supposedly accidentally got sent a copy of Margaret Thatcher's biography by her book club. So we kept it. Didn't pay for it. I drilled a hole through it, put a big steel bolt all the way through and super-glued it so you couldn't undo it. If, for some bizarre reason, I was given a copy of Blair's book, I would find something horrible to do to that as well. Certainly wouldn't read it [bursts into a big laugh]. No way.

What ‘horrible' things would you do to it?

I haven't thought of it. It took me a while to think of the bolt thing with Thatcher's one. I don't know what I would do with a Blair one. Something on the same lines. You have to make it unreadable and express your contempt for it at the same time.

You are also in favour of Scottish independence.

I have never sort of been a romantic independent. I am a pragmatic independent in that way, you know? I think an independent Scotland that is in Europe would make sense. I certainly think that especially, it kind of depends on what happens with Britain, with England, as a whole. I think that so many people seem to really resent being part of the European Union, there is a possibility you might see British politicians who want to take the whole of Britain out of the EU. That being the case, Scotland might choose to say, ‘Well we will stay within it, thank you.' Who knows?

So yeah, I am a pragmatic Scottish National Party supporter. But also because they have had more left-wing policies than the other major parties in Scotland. We will see how that changes.

I think Scottish Labour might swing further to the left and try and distinguish themselves from the British Labour party as it were a bit more. But that remains to be seen.

You have as a writer called for the boycott of Israel. What made you take this step?

The final straw was the attack on the peace convoy. I mean it's a hit where it hurts kind of thing.

I think the sports boycott of South Africa really hurt the South Africans, because they weren't bothered about intellectual stuff so much but sports really matters to them.

In the same way, the Jewish people are rightly proud of their intellectual history. So even talking about intellectual boycott or artistic boycott — that hits where it hurts.

It's a sad thing to have to even suggest doing something like that. But I think the treatment the Palestinian people are getting is so grotesque, so unbalanced and just so cruel. So you have got to try and do something.

It's a very small thing to be trying to do. But it is kind of all I have got at my command, as it were.

How has politics had an impact on your work as a science fiction writer?

Not enough, I think. I would like to be more political but I struggle to make it happen. I think there is a kind of background political stuff going on in the Culture. Culture is where I think society ought to be heading. It's my ideal society. There is politics on a fairly superficial level in most of the mainstream novels. But it is usually a character who is kind of my mouthpiece, spouting left-wing rants or whatever. I'd love to get the politics on a deeper level. But I struggle to do that. It just doesn't seem to be in me, I am afraid, which is a shame. However, I remain optimistic and still have ambition, so maybe one day I will write a proper political novel.

Finally, who in your view is the greatest contemporary British writer?

Oh, I honestly don't know. I am really bad at that sort of stuff. I have so many books behind, you know years behind, usually. I have never read any of the Booker prize nominees for any given year. I am almost tempted to go really left-field and say someone like Alan Moore or maybe Alasdair Gray. But I don't know, I am not very good at these questions. It's not the way my mind tends to work. I am not good with lists either. Let's say Alan Moore for the sake of it. Yeah.

And Scottish?

Definitely Alasdair Gray.

- Syed Hamad Ali is an independent writer based in Cambridge, UK.