A paradox that shaped Joseph Heller's life

Joseph Heller, as the man who wrote, and lived with having written ‘Catch-22’

Fifty-one years ago, nobody used the term "Catch-22" to describe a victim trapped in a contradictory, often bureaucratic, paradox. Not even Joseph Heller, who had spent seven years writing his satirical Second World War novel; he was still calling it "Catch-18". Then, just months before its publication, news that bestselling author Leon Uris had grabbed the numeral for Mila 18 forced Heller and his editor to change the title. In 1961, Yossarian, Milo Minderbinder and Major Major met their public in Catch-22.

Few authors ever make a cultural impact as broad or as lasting as Heller did with Catch-22. But there was a catch: It was the 38-year-old writer's first book, and he had a long life ahead of him; he died at 76 in 1999. He wrote other, quite possibly better, books — he and many others thought his second novel, Something Happened, was his best — yet it is Catch-22 that lasts.

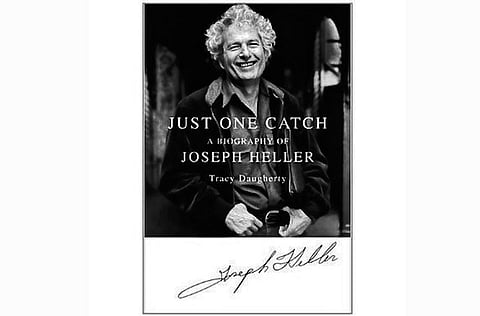

On the 50th anniversary of the publication of Catch-22, two new books remember Heller. An intimate view comes from daughter Erica Heller in Yossarian Slept Here, and Tracy Daugherty's Just One Catch shows the path Heller took to become the man who wrote the novel and where he went from there.

Joseph Heller was born in Brooklyn to Russian Jewish immigrant parents in 1923 and brought up in the crowded ghetto of Coney Island with his older half-brother and half-sister. When he was 4, Heller was lavished with attention and gifts and enjoyed a rare party — unfortunately, the occasion was his father's funeral. If this early encounter with inverted logic (treats are for funerals!) helped form the dark-yet-giddy current of Heller's writing, Daugherty doesn't make such an explanatory leap. He has assembled an appropriate amount of evidence for a biography, but he seems unsure what to do with it.

Heller's own memoir, Now and Then (1998), provides much of the material Daugherty includes about Heller's early life. He was a socially adept man, bored by school, raised by his old-world mother with the help of his half-siblings. He delivered telegraphs as a teenager, was sociable and handsome and mostly broke, and enlisted to fight in the Second World War.

Like his famous character Yossarian, Heller was a bombardier, flying in the glass nose of a B-25, and like Yossarian, the number of missions he had to fly kept creeping up. He was stationed in Corsica from 1944 to 1945 and, after 60 missions, finally shipped home. Upon his return, Heller's half-brother coaxed him to take a short winter visit in the Catskills, where he met Shirley, his future wife, after being lassoed by her strong-willed mother. "I can only marvel at the pair of them now," Erica Heller writes, "my grandmother and my father, both so cagey and indomitable. They had a great deal in common, although neither would have agreed on that." It is these intimacies that make Heller's book a vital read. She didn't idolise her father, but she portrays his complexities with sympathy.

Of her father's friendship, she writes, "the currency was frequently sarcasm — snarling, brutish, yet often delightfully and deliriously funny." This pithy description of her father's character is fuller than anything Daugherty gets to: He has found the bones of the story but lacks its connective tissue and the man at its heart.

Daugherty is good at explaining the evolution of Heller's writing career: how he found his devoted agent, Candida Donadio, who became legendary after Heller became a star. And how Donadio found a young Simon & Schuster editor, Robert Gottlieb, who likewise would become legendary thanks to Catch-22. He also aptly portrays Heller's friendships with lifelong buddies Mario Puzo, Mel Brooks and the artist Speed Vogel, who were among a men-only weekly dinner group that met for years. There are tantalising hints of another level in Heller's emotional life. Daugherty mentions that Heller carried on affairs with women in his advertising circles both before and after Catch-22 was published, but they are little explored.

Heller is writing about her memories of her parents together as much as her father alone. As if to protect her mother, she allows one dalliance — whom she dubs "Dr Bugs" — to stand in for all her father's philandering. Like the best memoirists, Heller reveals her own mistakes. When Shirley was finally driven to seek divorce in the 1970s, she documented Heller's affair with Dr Bugs. Joe insisted his estranged wife was paranoid, and Erica believed him. Then in 1981, Heller fell ill with Guillain-Barre syndrome, a devastating neurological disorder that put him in the hospital, paralysed. Visiting one day, Erica pulled back the curtain and was astonished to find Dr Bugs standing at her father's bedside; she suddenly realised that her mother was right, and her father had lied to her over and over again.

Daugherty's Just One Catch sets out the markers of Heller's life clearly enough. It may lack for artistry and insight, but it is the first biography of Heller and a decent starting point. Meanwhile, the serendipity of Erica Heller's memoir begs the help of a supplementary timeline, but it is much deeper and feels like all a reader needs to get the feel for the man who wrote, and lived with having written Catch-22.

Yossarian Slept Here: When Joseph Heller Was Dad, the Apthorp Was Home, and Life Was a Catch-22 By Erica Heller,Simon & Schuster, 288 pages, $25

Just One Catch: A Biography of Joseph Heller b Tracy Daugherty, St Martin's Press, 560 pages, $35.