Henri Matisse: Drawing with scissors

The dazzlingly bright cut-outs the Frenchman made in his last decade show a period of vitality and radical reinvention

At the start of the Second World War, Henri Matisse found himself, for the first time in his life, confronted by an empty studio. He had lived and slept with his work ever since his beginnings as a poor art student, flitting from one rented attic to the next, carrying nothing but his canvases with him. But in his 70th year a bitter separation dispute with his wife meant that by late summer 1939 everything on his studio walls had been taken down, crated and stored in bank cellars for lawyers to fight over.

France declared war in September and was swiftly invaded, defeated and occupied by German forces. Matisse fell gravely ill and spent much of the next two years struggling to survive recurrent crises that threatened his life. In 1943, when German armies poured down through France to meet allied forces fighting their way up through Italy, Matisse was a bedridden invalid, living in a war zone in southeast France with German troops in his basement and allied shells exploding in the garden.

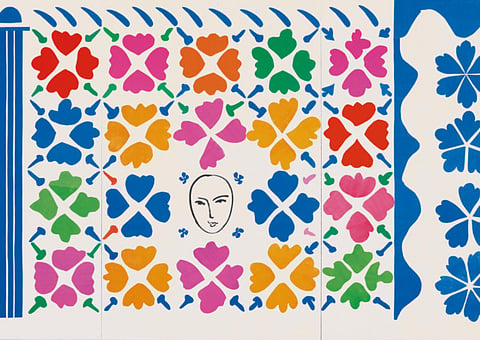

It was at this point that he cut a man out of white paper, a drooping pinheaded figure, all sagging limbs and blazing red heart, mounted on a black ground with bombs detonating around him. He called it “The Fall of Icarus”, after the ancient Greek who fell to his death because he had tried to fly too near the Sun, but Matisse’s “Icarus” marked a beginning, not an end. It turned out to be the first step in a process of radical reinvention that would see him abandon oil paints altogether in favour of new techniques based on cut and painted paper.

His doctors had given him, at most, three years to live after an intestinal operation in 1941. His mobility from then on was minimal and his strength greatly diminished, but the work he produced in his final decade suggests inexhaustible imaginative power and vitality. He made an astonishing number of increasingly ambitious cut-paper compositions, setting up a production line after the war in what he called his factory in Nice, where studio assistants covered sheets of paper with gouache mixed to his own direction in colours almost blindingly bright.

He said he was drawing with scissors, cutting directly into colour, abolishing the conflicts — between colour and line, emotion and execution — that had slowed him down all his life. “I do it in self-defence,” he said sadly, when Louis Aragon asked how work of such brilliant, reckless exuberance could have emerged from the darkest days of the war.

From the summer of 1946, a steady stream of images invaded Matisse’s walls, starting with the bedroom of his Paris flat where he cut a swallow out of white writing paper to cover up as cuff mark on the shabby brownish wallpaper. It was succeeded by a fish, then a second and a third, until gradually the whole width of the wall was submerged under a swell of marine life surfacing from buried memories of a trip to Tahiti made 16 years earlier. Seabirds, fish, shells, sharks, strands and curlicues of seaweed eventually covered two walls(later transposed by a resourceful young textile-maker, Zika Ascher, on to two silkscreen panels, “Oceania” and “Polynesia”).

They were followed by a tidal surge of cut-outs flooding Matisse’s interiors, sweeping round corners and over doorways, immersing fixtures and fittings under successive waves of fruit and foliage, acrobats, dancers and swimmers diving, floating and swooping round the rooms from floor to ceiling. Portrait heads swarmed under the cornice: a slender, hoop-shaped girl in a blue bodysuit with green stockings and a skipping rope bounded up to the height of the lintel. At one stage, the sleek, lithe, pantherine “Negress” — a minimalist giant created largely from slashes and slits — very nearly strode off the wall on to the floor.

Images took over all available space, commandeering salons, dining rooms, bedrooms and studios wherever Matisse went from his Parisian apartment to the little suburban house he rented on the outskirts of Vence in wartime, and even the mighty marble halls of the vast deserted apartment block high above the city of Nice where he ended up. The stained-glass windows for the chapel at Vence — a project that took Matisse four years to complete at the height of his powers — were designed from his bed entirely in cut and coloured paper.

Matisse grew old but his work did not. People who visited him in his late 70s and early 80s described him sitting up against his pillows with scissors and paper, twisting and turning the coloured sheets beneath his blades to release a steady stream of fragile spiralling shapes that floated down to subside on the bedspread below like flotsam washed up by the sea. The paper scraps were retrieved, pieced together and meticulously pinned in place according to the artist’s instructions. “He knew what he was looking for,” said one of his assistants, “but we didn’t.”

The hypnotic quality of the whole operation reduced those who watched it to stupefied silence, among them Picasso, who came regularly with his girlfriend to check up on his old rival. What baffled Picasso and enchanted his companion was the streamlined ease, speed and cutting-edge modernity of the entire procedure. “It was pure joy to be able in 10 minutes to do something that was of now, now, now,” Francoise Gilot said.

Matisse had given his life to projecting an inner reality strong enough to withstand the competing claims of the external world. Now the seagulls he had watched circling the sewage outlet on the Nice seafront, the doves that once flew freely in his studio, were internalised in the sensation of flight that drove the path of his scissor-blades. Forests of red, blue, black and ochre fronds sprang up around him.

When a girl from the local opera came to dance for him, he captured her movement as a flash of swirling colour like the flick of a fan in “Creole Dancer”. He sketched a garden snail, holding it between thumb and forefinger, and recreating it afterwards in the vast shell-shaped spiral of coloured blocks that make up the Tate’s mural, “The Snail”.

Nothing could stop him. His eyes gave out (the optician said his retina could not keep up with the pace at which his brain processed colour), his hands swelled up, weakness shortened his days, pain and delirium swallowed the nights. More than one of his young assistants reached the verge of collapse, but all of them agreed in retrospect that the atmospheric tension of Matisse’s studio had been as exhilarating as it was exhausting. “It was a race,” said another of them, “an endurance course that he was running with death.”

Most of Matisse’s French contemporaries dismissed the few cut-outs that were shown publicly in his lifetime as, at best, paper jokes unworthy of a serious artist; at worst, the pictorial maunderings of second childhood. Matisse himself talked of abstraction and the absolute, saying he wanted to distil each image down to its bare essence, and insisting that, however incomprehensible it might seem in its day, his latest work would speak to the future. Sure enough, 60 years after his death, the curators of “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs” talk of proto-installation and proto-environment art, an improvised and interactive work-in-progress that involves the viewer and invades his or her space.

“It breathes, it responds, it’s not a dead thing,” Matisse said of one of his cut-outs. The Tate’s team under Nicholas Cullinan plans to revitalise these works by highlighting their fluidity and transience. Individual compositions are traced back to their beginnings, and forward as they emerge stage by stage from the documentary record.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Hilary Spurling’s “Matisse: The Life” is published by Penguin.

“Henri Matisse: The Cutouts” will run through September 7 at Tate Modern, London.