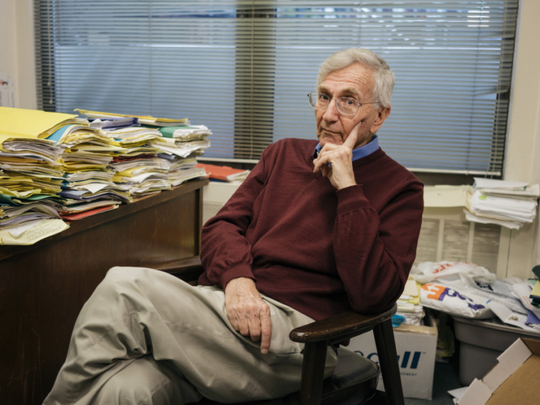

Within minutes of meeting Seymour Hersh you understand why he is so good at getting people to confide in him. His lack of pretension is disarming. He is direct, he asks questions, he listens. He hits you with a volley of jokes and anecdotes. Even at 81, he cannot contain the energy coursing through him, clinching a killer off-the-record story by bouncing out of his chair to pull a classified document from the files on his desk. “Can you believe this [expletive]?” he roars, laughter taking the edge off his outrage. It’s a display of trust that invites reciprocation. It is hard to resist.

Over the decades, Hersh has persuaded some of the most secretive and powerful people in the United States to open up. He made his name in 1969, with his expose of the My Lai massacre — where between 347 and 504 unarmed women, children and old men were killed, and women and girls were raped, by American troops — and the military’s subsequent cover-up.

Thereafter, he established a reputation as a reporter of extraordinary tenacity, one that whistle-blowers could trust. He broke stories on the illegal bombing of Cambodia in 1970, the CIA’s complicity in the 1973 Chile coup, and he revealed how the agency was spying on American citizens in 1974. Writing for The New Yorker after 9/11, he exposed the abuse of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib.

“People talk to you if you have information,” he says. “And I always had information... People in the CIA and the NSA would talk to me. Senators would talk to me. It was because they knew I was smart and good. I was operating at a different level to other people.

“But it wasn’t easy. Investigative reporting never is. My job is to walk into an editor’s office, throw a dead rat full of lice on to their desk and say, ‘this is what I want to do for the next three months, it is going to cost you a lot of money, you are going to get sued, you are going to get threats, and you are going to lose customers — but let’s go at it!’”

The two-room office in which Hersh has worked for the past 28 years is in downtown Washington DC, just a 15-minute walk from the White House, a perch deep inside enemy territory. He likes it like that. In the front room, boxes of documents compete for space with advance copies of his new memoir, Reporter. On the wall are some of the many awards he has won for his reporting. In the back room, where he works, he sits surrounded by files and legal pads, filled with his spidery handwriting. Everything is in hard copy, nothing on computer, Hersh having learned through his own reporting the sheer scope of electronic surveillance.

For Reporter, he had to dig the dirt on a new target: himself. “The idea of writing a memoir? No [expletive] way. I have two aphorisms: ‘Read before you write’ and ‘Get the [expletive] out the way of the story’... but I had been working on this book about Dick Cheney [vice-president under George W. Bush] and I was stuck. I went to Sonny Mehta, who runs Knopf [the publishing house], and told him I would pay back the advance. He said instead of doing that, I should write a memoir. I always thought I’d hate it and it was horrible at first. But you know what? I actually enjoyed it.”

Having made powerful enemies, Hersh is understandably protective of his family (he has two sons and a daughter with his wife, Elizabeth, a psychoanalyst) and they remain in the background of the book. He does write about his difficult childhood, though, growing up on the south side of Chicago, the son of Jewish immigrants. “My father never talked about anything,” he says. “I later learned he came from a village that had been completely wiped out by the Nazis. In his own way my father was both a Holocaust survivor and a Holocaust denier.”

If they stepped out of line, Hersh and his twin brother were hit with the leather strop their father used to sharpen his razor. “I remember my brother once said ‘no’ to him and he slapped him across the face,” he says. “He was eight.” Hersh didn’t care for authority figures after that.

His father died of cancer just after Hersh finished school, and while his brother went to university, Hersh took over the family’s dry-cleaning business. While working, he began studying at the University of Chicago and in 1958, when the family sold the shop, he fell into a job as a crime reporter, before joining the Associated Press, where he reported on the Civil Rights movement and got to know Martin Luther King Jr. Fiercely independent and fired up by injustice, above all, he was good at the job.

In 1969, Hersh moved to Washington DC to report on the Vietnam War, and, as a 32-year-old freelancer, received the tip that made his career, when a lawyer called him to say that William Calley was being court-martialled for killing dozens of Vietnamese civilians at My Lai. Hersh’s account of tracking down Calley to where he had been hidden at Fort Benning, Georgia, reads like a cinematic thriller. “I have had about a million movie offers,” he says.

Hersh, though, has a complicated relationship with My Lai. The scoop won him the 1970 Pulitzer Prize, but the details he heard about the violence inflicted upon infants that day brought with them a heavy emotional burden. “I had a two-year-old son at home,” he writes in Reporter, “and there were times, after talking to my wife and then my child on the telephone, I would suddenly burst into tears, sobbing uncontrollably.”

He is particularly proud of his 1974 New York Times report on the CIA’s illegal domestic spying operation. “What I found out later was that they had been tracking me since 1972,” he says. “They had transcripts of every [on the record] conversation I’d ever had. These [expletive]. But I had the place wired. I had a source right at the top. And look at this.” He pulls out a declassified CIA file. “Here is [William] Colby, who is the head of the CIA, saying I know more about what’s going on in the place than he does! It’s in a secret transcript. I am in heaven.”

Keeping up with Hersh is hard. “This is a lonely job so when I get the chance to talk, I talk,” he says, jumping between decades, pulling names, dates and clandestine operations from the ether. At times, the digressions are so abrupt that you wonder if he is losing his thread, only for him to return perfectly to the original point. He enjoys making fun of his younger self, of the times he screwed up, of how demanding and difficult he could be (there is a story of him hurling his typewriter through a window at the New York Times, and another about his meeting John Lennon and not having a clue who he was). “People who have read the book are surprised,” he says, “because I am known for being somewhat full of myself.”

Some of his more recent reporting — controversial pieces on the killing of Osama Bin Laden in the London Review of Books, for instance, and on the use of chemical weapons in Syria in Die Welt — has resulted in accusations that his work has become conspiratorial and thinly sourced. “I don’t care,” Hersh says. “It’s always been like that. People did not want to believe me on My Lai. I will let history be my judge.”

He has always had little time for much of the media. “Even though we know that they lie, cable news treats official announcements as the truth, with no attempt to verify them,” he says. “There aren’t enough journalists doing investigative work, challenging the official accounts.” He worries how much of what the American military does goes under the radar. “We are in 76 countries right now and most of those forces are under Special Operations Command,” he says. “There are good guys on the inside, but you have to stop the special operators. But we have a president who doesn’t understand, doesn’t pay attention.”

Trump, he fears, isn’t going anywhere soon. Hersh believes not only that people are overplaying the potential findings of Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian involvement in the 2016 presidential election, but that the media’s obsession with Trump is predominating. “Trump is catnip,” he says. “They are getting more customers, more circulation, more ratings. And all the Democrats are doing is running against Trump. That’s what Hillary [Clinton] did. So, what I say is, ‘look out Democrats!’ because I can see him getting re-elected.”

Hersh is no passive observer of the political scene. One of the reasons he was hesitant about writing a memoir is that it might send out the message he was done with reporting. He points at the huge pile of files on his desk. “I think I have figured out a way of doing the Cheney book,” he says. Then he points at a second pile on the floor: “That’s all on Hillary”. He indicates a third: “Those are from a defector from Pakistani intelligence. Amazing [expletive] that I don’t know what to do with. Pakistan has over 100 nuclear bombs. And they are completely out of control. How is this not the most pressing foreign policy issue of our time?” He sure as hell wants to find out. The phone rings three times during our interview, sources and contacts touching base. “There is no way I could stop,” he says. “I’m a junkie.”

–The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2018