In substance, Joe Biden’s new memoir, Promise Me, Dad, is a classic “year in the life” memoir. The book starts just before Thanksgiving 2014 and covers the three signal story lines of his next year: the gruelling illness and death of his elder son, Beau, of brain cancer at 46; his difficult decision not to pursue the Democratic nomination for president in 2016; and his welcome workload as vice-president, particularly on foreign crises in Iraq, Ukraine and Central America.

Scene by scene, Biden toggles briskly among his three story lines: from an emotional family meeting at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, to an urgent phone call with Iraqi Prime Minister Haider Al Abadi about Daesh, to a friendly lunch with President Obama, who is tactfully trying to discourage the vice-president from pursuing the Democratic nomination. Leaping from strand to strand, Biden creates a propulsive energy and a distinct hope that things may turn out differently — better — than we know they will.

Promise Me, Dad may not be as probing as President Obama’s bildungsroman, Dreams From My Father, or as thoroughly thorough (at 494 pages) as Hillary Clinton’s What Happened. But it is impressive on its own terms. Section by section, Biden splices a heartbreaking story with an election story and a foreign affairs story. And in so doing, he offers something for everyone, no matter which strand draws you in.

Of course, the centrepiece of the book is Biden’s unflinching account of the death of his son, a two-term attorney general and a major in the National Guard who had been deployed to Iraq in 2008. Here, Biden exudes the same Everyman quality that’s been on display for more than 40 years of public life. He shares his grief, knowing that everyone grieves. Ultimately, his message is this: By engaging with life, as bewildering as that may seem after a tragedy, we can thrive again.

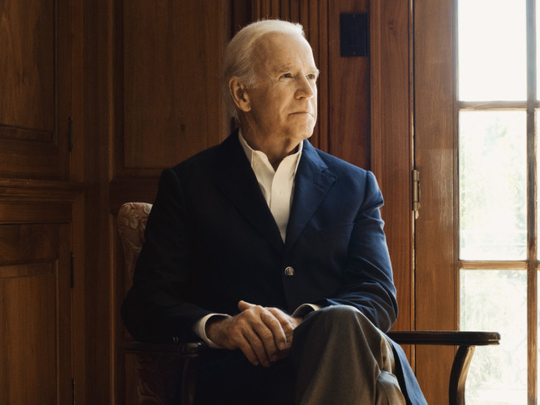

Last month, Biden sat down in the book-lined study of his home in a leafy neighbourhood of Wilmington, Delaware, to discuss his memoir, which was published on November 14.

Why write this book? Why tear your heart open again?

For my kids. Look, I have two beautiful grandchildren. I have a thousand pictures of them all around. For a year, when they were building a home, they lived here: Beau, [his wife] Hallie and the two kids. I wish they’d never moved. But after he died, the kids would come into my bed and lie on my chest: “Pop, tell me stories about Daddy.” “Tell me the one about when he fell out of the tree.” “Tell me the one about when that guy went after Daddy and Uncle Hunt and beat them up.”

In planning the book, were there authors or memoirs, books about loss that spoke to you?

No. I didn’t want to be like anyone else. I’m not being facetious. And I didn’t want to write a book about grief. I didn’t want anyone feeling sorry for me. I wanted to celebrate Beau’s life and the people he touched. Beau had a strict code of honour. That may sound silly, but it’s true. My Dad had an expression: “Never explain and never complain.” I never once heard Beau complain. Not once.

When his brother and sister, Hunter and Ashley, stood up to give their eulogies, I don’t know how they did it, but I’ve never been prouder of them in my life. Hunter, who’s a beautiful writer, said: “My first memory of Beau was when I was 3 years old.” They were in the hospital [following the death of their mother and baby sister in a car accident]. Hunt had a skull fracture, almost every bone in his body was broken. And Beau, just 4, in the next bed, held his hand and kept saying: “Hunt, I love you. Look at me. I love you, I love you, I love you.” At the funeral Hunt said in 42 years that “he has never stopped holding my hand.”

I want readers to know that there are people like Beau in this world, who put country first, family first, friends first.

Let’s talk about the structure of the book. You keep three narrative strands running throughout the text.

It was all about time: seconds, minutes, hours — not months or years. We were either going to beat Beau’s illness or not, and we had a very narrow window. My assignments at the White House were similar. They weren’t about managing relationships; they were crisis management. If Prime Minister Abadi didn’t reach a deal with the Sunnis, the government would implode. It got down to minutes and phone calls and seconds.

For a famous talker, it’s a taut book.

Well, there’s a difference between talking and writing. When I’m talking with someone who’s looking for something — for assurance or help, for me to take a position — I try to engage them. I draw them out by talking, by listening to what they’re saying and what they’re not saying. But in the book, I had to be disciplined to bring all those strands together. I wanted to make my points as crisply as I could.

There’s a beautiful line in the book: “My story precedes me.”

And it does. Look, I was on top of the world in 1972. My sister managed my Senate campaign and pulled off the most improbable upset. I’m down in Washington, hiring staff, and I get a call from a young woman who says: “Your wife and daughter have been in a terrible accident. You have to come home.” I said, “She’s dead.” And she said yes. So, I know the stages of grief, like a lot of other people. From the pain, to the sense of hopelessness, to recovery, it’s all about time.

There’s an undertow on every page, a knowledge that we’re all suffering. Did that predate 1972?

I used to be a very bad stutterer. Everybody thinks I know Irish poets because I’m Irish. But I know them because of my uncle, an educated bachelor who lived with us, off and on. He had a volume of Yeats. And I used to get up at night and put a flashlight on the mirror, practicing and practicing, reading aloud from those books. Everybody has a burden to carry.

Maybe that’s why the strands of the book bleed together? When one of Beau’s doctor visits goes well, there’s an optimism that carries into the next section about Iraq.

I wanted to write precisely about the crises and dilemmas I faced as they intersected in the moment. I wanted to show that in the ebb and flow of life, nothing is totally separable. As much as I try to compartmentalise, what you’re doing in one phase of your life washes over and affects the others.

And occasionally, the crosscutting made me think you’d actually cheat death, that Beau would live.

Oh! We were praying and working and believing. I’ve always been an optimist. When I had a couple of cranial aneurysms [in 1988] and the doctor’s were giving me less than even chances of living, I was still talking as if everything was going to be OK.

Several times, Beau says: Don’t look at me sad, Dad. Or: Promise me you’ll be OK., Dad. Did he ever let you comfort him?

One night, when it was clear that the odds weren’t good, he asked me to stay after dinner at his house, about a mile from here. He said: “Dad, I know you love me more than anyone in the world. But promise me you’ll be OK. I’ll be OK., Dad.” He had come face to face with his mortality. He watched me go through the loss of his mother and sister. And he didn’t want me to turn inward. He didn’t want me to give up on the robustness of life.

You were reluctant to confide in President Obama about Beau.

It was complex. I didn’t want him to carry the burden of feeling sorry for me. Several times, when we talked about Beau, he started sobbing, and I had to console him. I didn’t want to put him through that, not with all the responsibility he had on his back. I also didn’t want him to do what most people would do, what my staff wanted to do: Have Joe do less. I had to do more. And I had my diaries. I’m able to write and express emotions fairly well. And I was completely honest with myself in those diaries.

Let’s turn to the 2016 election. You write that President Obama was pretty discouraging about your running for the Democratic nomination. But in the book you also say that the race was coming to you: The badly beaten middle class, the populism, the authenticity.

What people don’t realise is that Beau was essentially diagnosed with a death sentence in 2013. Virtually nobody makes it. I had an obligation to tell the president because of my duties. So, he knew what was going on. By late 2014, we were walking after lunch, and Barack said: “Joe, if I had the power of appointment, I’d appoint you president. We agree on the issues, I know your leadership skills, and I think you’d be the best president.” But he had other pressures. I felt them, too. If I were to say “I am not going to run,” in the face of all this data that’s coming in saying, you can do it. If I said that, everybody would have known there was something wrong with Beau. I would have violated my commitment to him to keep it secret. The piece that complicated it is that after he passed, it was clear that he really wanted me to run.

Both sons wanted you to run.

I believe Beau, looking down, understands why I didn’t run, and he accepts it. Beau, Hunt and Ashley didn’t want me stepping back. They thought that what limited talents I have that may not have been suited for winning decades earlier were exactly what the public was looking for now.

There’s a scene in the book where Hillary Clinton comes to visit with you to see if you’re planning to run for president. You write that she was propelled by forces not entirely of her own making. What does that mean?

I think she wanted to be president and would have been a good president. But she also had to understand how difficult her life was going to be, how she would be vilified. But Hillary is also driven by the need to empower women. Having known her for a long time, I can’t believe she didn’t think: What will young women in the world think if I walk away?

We’re so dug in and divided now. Do you really think a President Biden could make a difference?

The obvious answer is: I don’t know. But I have always been good at bringing people together. Trying to understand the other person’s perspective, and trying to figure out how to get to “go.” That skill was always useful, but it has a higher premium now that we don’t work together as much. And that’s why I wrote this book about Beau. I wanted people to see how honourable political life can be. He had so many chances to advance himself — he was offered my Senate seat when he came back from Iraq — but he wouldn’t take it. He wanted to earn it. Beau’s ambition was to be a man who always did his duty.

–New York Times News Service

Philip Galanes, a lawyer in private practice, writes the Social Q’s and Table for Three columns for the New York Times.