Best history books of 2017

How the Victorians acquainted us with our bodies, landmark studies of Stalin and the holocaust, and traitors laid bare

History books should give us insight and information, surprise and entertainment, and allow us to see the world, an incident or a character differently. Nicholas Shakespeare’s Six Minutes in May (Harvill Secker) delivers in abundance. It revolves around the British prime minister Neville Chamberlain’s announcement to parliament, on May 7, 1940, of the British military defeat by German forces in Norway: 4,396 men had died. Few people expected Chamberlain to lose his post; fewer still thought that Churchill, architect of the Norway fiasco, could replace him. The machinations that led Churchill to power make for a great story; the wider context and its effect on the war give the story significance. Shakespeare shapes all with an historian’s thoroughness and a novelist’s flair.

The gory world of Victorian surgery is the subject of Lindsey Fitzharris’s The Butchering Art (Allen Lane). At University College Hospital, London, in 1846, a surgeon — “the fastest knife in the West End” — amputates a patient’s leg, watched by a crowd in off the street. The crowd was a regular feature, the use of ether to soothe pain — known as “the Yankee dodge” — was a novelty. Enter Joseph Lister. Inspired by Louis Pasteur’s work on microorganisms, Lister fights infection and the establishment. The ensuing blood-spattered story leads to the transformation of the brutal world of Victorian medicine.

Physicality is at the heart of Victorians Undone (Fourth Estate). Kathryn Hughes, celebrated for biographies of George Eliot and Mrs Beeton, looks beyond crinoline and starched collars to bring us “tales of the flesh”. The book focuses on the physical attributes of five characters, from Queen Victoria’s confidante Lady Flora Hastings’s belly to Charles Darwin’s beard (grown to help with facial eczema) and George Eliot’s hands (one larger than the other). On the way, Hughes spins wonderful and weird tales of how industrial revolution Britons, crammed into cities, learned to cope with their neighbours’ bodies.

Belonging (Bodley Head) is volume two of Simon Schama’s Story of the Jews, but stands on its own, ranging from the expulsion from Spain (1492) to Theodor Herzl in old Jerusalem imagining the new city the Jews would build (1900). Schama writes with power and energy, and his patchwork of individual tales crosses the world to describe the many sides of Jewish experience. The ironic title refers both to the Jewish quest for a safe home and the suspicion levelled against Jews, in the age of empires, for belonging to a supra-national organisation.

Volume one of Schama’s work appeared four years ago; if you can’t wait for volume three, turn now to The Holocaust, A New History (Penguin). Laurence Rees’s shattering account of the rise of Nazism and the resultant genocide is a masterpiece of concision, the best single-volume portrait of the holocaust.

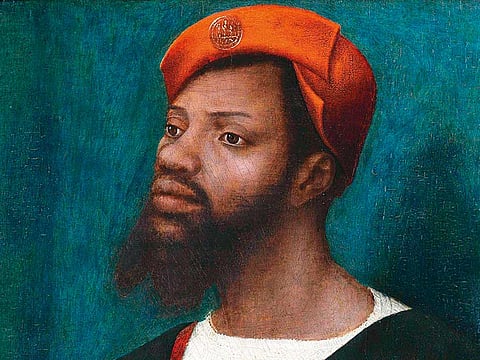

The 16th-century Tudor world was dominated by religious schisms: Henry VIII looking for an heir, Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots losing her head, Elizabeth facing a Catholic Spanish armada... All this is familiar, and white. Miranda Kaufmann’s achievement in Black Tudors (Oneworld) is to add racial diversity to the picture. We meet the likes of John Blanke, a royal trumpeter, and Anne Cobbie, a Westminster prostitute, both free and flourishing. Kaufmann has rescued them, and many others, from the obscurity of official registers, and in the process changes our image of the age of doublets and codpieces.

You need time to savour Stalin: Waiting for Hitler (Allen Lane), in which Stephen Kotkin fills 900 close-typed pages with an epic telling of how Stalin consolidated power, killed millions of his citizens and then miscalculated Hitler’s intentions. This is a monumental study of a ruthless man intent on making his nation a world leader, whatever the cost. The tale is made mesmerising by the personal details with which Kotkin, professor at Princeton, makes his characters come to life.

The Traitors (John Murray) of Josh Ireland’s debut work are Britons who sided with the Nazis. He follows four of them, linked by common cause, the most famous being William Joyce. Better known as Lord Haw-Haw, he fled to Germany in 1939 and spent the war broadcasting pro-Nazi propaganda. Ireland tells his four characters’ stories with immense skill, to reveal their motives and lead them to inevitable ruin. In the process, he raises a question of great importance now: what is patriotism, and why should we care?

–Guardian News & Media Ltd