Zaha Hadid’s legacy

Renowned as the Queen of Curve, the late Zaha Hadid’s legacy lives on in the UAE’s eclectic skyline

It didn’t open during her lifetime, but Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid’s first studio in the Middle East has perhaps become even more influential than she could have imagined. Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA), the studio that carries on with her legacy, opened an office in the Dubai Design District in November out of necessity as demand for Hadid’s work quickly grew in the UAE and the wider region. Today, ZHA is continuing the many architectural projects and master plans Hadid started here. A total of 16 projects are currently in the works in the Middle East and North Africa, including landmark buildings, projects and master plans.

“Zaha Hadid Architects is working with the many diverse histories and cultures of the region to address important issues in a meaningful way — contributing to the development of more ecologically sustainable and integrated built environments,” a statement by Hadid’s office said. “Our office in Dubai has been established in response to the solid growth in demand from new and existing clients across the region; providing even greater levels of assistance, coordination and communication with our increasing client base throughout the Middle East.”

Born in 1950 in Baghdad, the award-winning architect, nicknamed the “Queen of Curve”, is globally renowned as the most successful woman architect and one of the most influential in the industry. Having studied in Beirut, Rotterdam and London, Hadid had conducted architectural lectures at renowned American universities, and started working on projects in Europe, the US and Japan. Her first major Middle Eastern commission was in Abu Dhabi, the Shaikh Zayed Bridge, in 2007.

Hadid’s unexpected death in March last year left a deep void in the world of architectural design, but her legacy lives on. As a posthumous honour, a permanent memorial to Zaha Hadid will be placed at The Opus towers, a structure she designed in Dubai’s Business Bay for developer Omniyat. The developer also set up the Zaha Hadid/Omniyat Fellowship Fund at Harvard University, where Hadid held a professorship in the 1980s. The fellowship is meant to support Middle Eastern students during their master’s degree studies in architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

In fact, the recognitions are coming relatively late. Seen by many as the world’s most famous female architect, Hadid did not instantly rise to fame in her home region. Owing to her studies mainly in the UK, she started to design buildings and interiors for clients in Western Europe in the late 1970s and early 1980s, with her first realised works being a social housing complex and a fire station in Germany in 1993 and 1994, respectively, followed by two design projects in Japan.

First breakthrough

It was not until she laid out the design of some of her most acclaimed works, the MAXXI Museum in Rome starting from 1998, and the Guangzhou Opera House starting from 2005, that Arab clients would become interested in her. By that time, she had already realised some remarkable structures, such as the iconic Bergisel Ski Jump in Austria, a number of acclaimed contemporary art centres and museums in the US, and industrial and science buildings and bridges in Europe. In 2004, she became the first woman to be awarded the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize, considered the highest honour in the field and one of many honours bestowed on her across the world.

In 2007, after having been commissioned with the design and planning for the landmark of Abu Dhabi, Shaikh Zayed Bridge, the path into the Middle East finally opened. Shaikh Zayed Bridge wasn’t actually her first work in the Arab world, albeit it was her most significant at that time. In 2006, she was announced winner of the design competition for the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs building at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon, a country where she briefly studied after her family left Iraq and moved to London in 1972. The Issam Fares Institute, completed only in 2014, was not only pushing the boundaries of modern architecture in the Arab world by featuring Hadid’s trademark futuristic appeal with multiple geometrically complex points of perspective, it was also a sort of political statement.

Deconstructivistic design

Issam Fares, former Deputy Prime Minister of Lebanon and billionaire businessman, wanted to shape the building in a way that went beyond contemporary Arab architecture, which was always eager to quote Islamic traceries such as dune shapes or traditional Muslim or Bedouin architecture and forms. Breaking with this habit was somehow new to Arab architecture and design, and probably the reason her first deconstructivistic design work in the Middle East, Al Wahda Sports Centre in Abu Dhabi, commissioned in 1988, was never realised.

For the Shaikh Zayed Bridge, she was much more compromising, giving the structure, which was finished in 2010, the shape of a wandering dune to capture what her clients, Abu Dhabi’s royal family, felt was best to symbolise the energy that the capital city radiates. Although that did not fully reflect Hadid’s legacy of deconstructivism, the floating structure with its dynamic lighting design based on subtle colours made the bridge a unique architectural composition and was ultimately her breakthrough in the region.

The subsequent list of commissions in the Middle East has become quite long, and while some buildings are under way, others are on hold, which is a result of the economic and political conditions in the region and Hadid’s untimely death. Major master plans at that time were the Bahrain International Circuit and the Cairo Expo City.

Her other projects in the Middle East include the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Centre, which is nearing completion in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. It is shaped in “a cellular structure of crystalline forms from the desert landscape”, as Hadid’s design studio describes it. Another project in Riyadh currently under construction is the King Abdullah Financial District Metro Station, a massive structure spanning over six platforms, four public floors and two levels of underground car parking, designed to be integrated within the urban context of the financial district and functioning as a transport hub for the district. Again, the entire outside design composition resembles patterns generated by desert winds in sand dunes.

Another ongoing project in the region is the King Abdullah II House of Culture and Art in Amman, Jordan, awarded in 2008. The project consists of a performing arts and cultural centre that includes a 1,600-seat concert hall, a 400-seat theatre, an educational centre, rehearsal rooms and galleries. The building is a carved structure, with voids crossing it that create several visual relations. The design resembles the rose-coloured mountain walls of Jordan’s region of Petra.

In 2010 Hadid was commissioned in 2010 by the Iraqi government to design the new building for the Central Bank of Iraq, her first project in her country of birth. The high-rise building, about 172m tall and situated on the banks of the Tigris River, is meant to signal a new phase of construction in a growing and developing Baghdad. In 2013, Hadid was also chosen to design the new Iraqi parliament building in Baghdad. The building will be built on a 20-hectare site in the western part of Baghdad, which was originally used by Saddam Hussein to partially construct a huge mosque.

The Iraqi government hopes the new building will be a “more potent symbol of the new Iraq”.

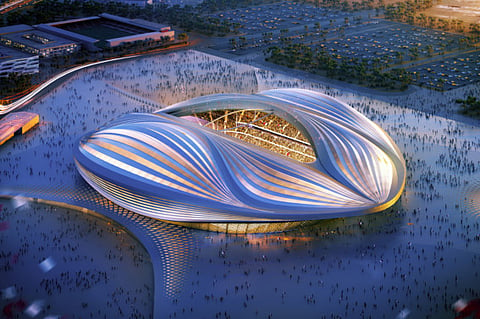

Hadid also designed the Al Wakrah stadium being built for the 2022 Fifa World Cup in Qatar. The 48m-tall stadium, which will also become the new home of Al Wakrah Sports Club, is due for completion in the fourth quarter of 2018. Hadid this time interpreted the forms of a dhow, the Arabian pearl fishing boat that is of great historic and cultural significance in Qatar.

UAE projects

After her initial success with Shaikh Zayed Bridge, Hadid landed a number of design commissions in the UAE, which are now being taken care of by the newly opened studio in Dubai. They include the Performing Arts Centre in Abu Dhabi, the headquarters of waste management firm Bee’ah in Sharjah, the Dubai Opera House, the Signature Towers and The Opus, the Dubai Financial Market and interiors of the ME Hotel in Dubai.

Standing out from among these projects is the Signature Towers, a combined office, hotel and residence development in Business Bay and designed way back in 2006. The structure, formerly known as Dancing Towers, although it is shown as an ongoing project on the website of ZHA. It is part of the Dubai Financial Market development, which is also on hold.

The Opus, also located in Business Bay and originally named The Void, is on its way to completion after several delays. Its structure looks like an ice cube that has almost melted into two separate parts at the bottom, but remains connected at the top. Commissioned by developer Omniyat, the building will also host the ME Hotel, for which Hadid designed the interior.

An earlier proposal to build a 2,500-seat opera house on an island in the Dubai Creek designed by Hadid, announced in 2008, was shelved following the economic downturn. The development has been replaced by a smaller one in Downtown Dubai, designed by a South African architectural company and completed last year. An ongoing cultural project is the Performing Arts Centre in Abu Dhabi, unveiled by Hadid in 2007. The concept shows a 62m-high building with five theatres, a music hall, concert hall, opera house, drama theatre and a theatre with a combined seating capacity for 6,300 people.

The arts centre is part of Abu Dhabi’s 270-hectare cultural district on Saadiyat Island. Hadid described the design “a sculptural form that emerges from a linear intersection of pedestrian paths within the cultural district, gradually developing into a growing organism that sprouts a network of successive branches, with the performance spaces as being embedded like pearls and exposed at the same time.”

Legacy

One of her latest projects in the UAE is the design for the headquarters of Bee’ah, a Sharjah-based environmental and waste management company, following an international competition in 2013. By the end of 2014, she revealed a design study showing a dune-shaped building.

While it is far from sure that all remaining projects in the Middle East will be completed, it is certain that Hadid’s legacy will live on in the region, where she has excitingly introduced modern architectural ideas.

“Long after the novelty of her gender fades from the public’s mind, she will be remembered for the swooping, sumptuous monumentality of her buildings,” says Tegan Bukowski, an architectural designer who works for Zaha Hadid Architects in London.

“Her work will continue… but her death [is] an irreplaceable loss, not just for those of us in her studio, but for an entire generation of architects.”