The deep cracks and dark calluses on Asha Rani’s little feet belie her age. Although only ten, her rough feet tell a painful tale – of the hundreds of kilometres she’s trudged over rocky terrain in the past five years, walking barefoot to school and back five days a week.

Her school is around three kilometres away from her home in Masi, a small village in Almora district in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand. The days begin early for Asha and her six friends in her neighbourhood. After a quick breakfast of chapatti and dal, she is off at 7am on a trek that will take she and her friends through shallow streams and over dry rocky land to the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it Almora Primary government school.

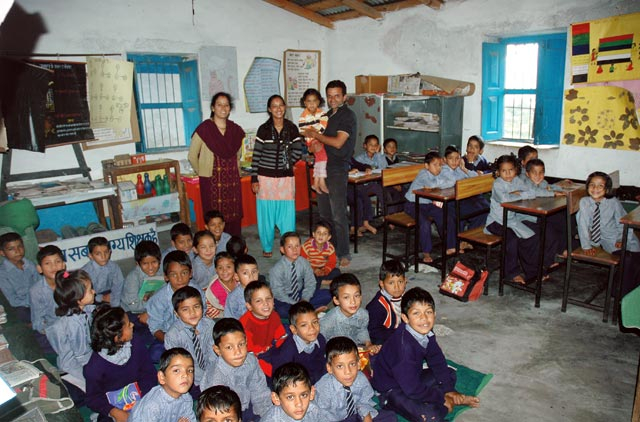

Until recently, the school was a single room that housed five grades, each separated by a thin tattered curtain. Here about 80 children studied together in the midst of a cacophony of different voices. Invariably, when Asha and her friends reached school, the teacher was absent. The reason? Teachers, appointed from other districts in the state and detesting the poor working conditions and lack of facilities, stayed away from work on the flimsiest of excuses.

Even when she was present, the quality of education left much to be desired, simply because the teacher lacked motivation. Although in grade 5, Asha was struggling to learn the English alphabet, and her knowledge of many of the prescribed subjects was poor.

But all that has changed in less than a year, thanks to the efforts of one man.

“It was while on a holiday in Rajasthan in early 2011 that I chanced on children in situations similar to Asha Rani’s,’’ says Madhukar Soni, 37, a former investment banker who was based in Dubai. “Something snapped in me when I saw the children struggling to go to a school where the facilities were pitiful.’’

He was so determined to improve their lot that he gave up his lucrative job and moved to Uttarakhand to try to improve the education system there.

Madhukar’s dream was to find a simple, low-cost solution to deliver high-quality primary education to impoverished villages. After much research, he developed a model schooling system. This included persuading multinational companies to part-fund the salary of teachers in schools as part of their corporate social responsibilty initiatives; asking charities to donate libraries; and approaching government bodies in villages to set up self-sustaining economic ventures that could fund the school’s upkeep. These economic ventures were also to serve as a source of income to parents so they would not have to migrate to cities where the children could end up entering the child labour market.

Today, almost a year since he implemented the model in three schools in Uttarakhand, his efforts are clearly paying off. Teachers are motivated, schools are better equipped and children’s knowledge levels have improved vastly. The process of getting to this point was not easy, however, says Madhukar.

Changing lifestyles and lives

A business management graduate from the London Business School, Madhukar led a charmed life before moving to India. Single, he had an apartment in Dubai Marina, drove a sportscar and had a enviable job with investment bankers Ernst & Young.

A three-week backpacking holiday on motorbike through the hinterlands of Rajasthan transformed not only his thoughts but also his life. Witnessing the struggles the children underwent for a basic education, trekking several kilometres each day to schools that were ill equipped and most times had no teachers, Madhukar’s thoughts went back to his grandfather, Tulsi Das Soni, who had been headmaster of one of the first schools in Rajasthan town Pilani. “Right then I decided to take a path less travelled,” he says.

“I spoke to the kids, their parents and the teachers, who all wanted to see an improvement in the education system,” says Madhukar. “But no one was doing anything about it. As always, we look for a change to come from outside. So I decided I would try to do my bit by revamping the system and making it interesting for the kids.”

After returning from his holiday, Madhukar, who had enough savings, quit his job in August 2011. He sold his apartment and car to fund his new venture.

His journey started with a plan to travel across northern India. Eight months later, Madhukar returned to his hometown in Rajasthan after visiting around 300 villages. In all of them, the one feature that struck him was the lack of educational facilities. The task Madhukar faced was daunting: to find a simple, low-cost solution to deliver good-quality primary education to the impoverished villages.

Madhukar drew up a plan. The hilly Kumaon region was to be the focus of his experiment. “That’s where I decided to start my new life, in Uttarakhand,” says Madhukar. The reason for this was that Uttarakhand seemed to be most in need of good schools. He initially concentrated on two Uttarakhand districts – Almora and Bageshwar – because there were a few charity organisations already working in the region.

“There are 51 villages in these two districts and I found that the kids in grade 5 did not even have the knowledge of a regular grade 3 student because of poor teaching methods.”

On average, there is a school for every two or three villages. The schools are funded by the World Bank. On average, a teacher is paid around Dh2,200 a month. While the pay is good, the working conditions leave much to be desired. Most schools have classes from nursery to grade 5, and on an average there

are 50 students in each school.

“Typically, these schools have two rooms – one housing children at nursery level as well as all five grades and a second that doubles as the administrative office, kitchen and the teacher’s living quarters. The teacher, who is appointed by the government, is also the principal of the school, teaches all six classes almost simultaneously!” says Madhukar.

“The students are also provided with a mid-day meal which is cooked on the premises – again by the teacher. The cooking, serving and cleaning and, of course, the administrative work eat up a lot of the teaching time.”

Since they are posted to these villages from different districts and have to live away from their families, the teachers usually go home for the weekend on a Thursday and return only on a Monday or a Tuesday.

“They don’t like living in remote villages due to the lack of amenities there, and the huge number of tasks they are expected to perform. Obviously, one person cannot run the whole show and the area that suffers is teaching.”

The road to improvement

After creating a plan that included steps to make the schools more conducive to education – providing modern teaching tools, improving teachers’ living conditions, motivating children and teachers to perform better – he approached Ernst & Young.

“We brainstormed with teachers, charities and Ernst & Young’s education foundation and concluded that we need to provide technology to give them effective education – essentially computers and software. We need dedicated helpers and teachers… Not necessarily very well-qualified or experienced, but motivated, with a desire to serve and most importantly who belong to the region and so can easily identify with the problems of the local people.”

Next step, Madhukar and his collaborators chose some helpers for the school. “We picked the brightest girls in the villages – girls because they would not move out of the village for jobs like boys would – and paid them around Dh500 a month as a stipend to help the teachers in their duties. These girls have a responsibility towards the community, are from the village so they know all the kids on first-name basis and, being young, they have the desire to learn and pass on the information to students.”

After acquiring enough experience and qualifications, these helpers go on to become teachers. The Ernst & Young Foundation funds one-third of the helpers’ salaries, while the village’s ‘panchayat’ funds the other two thirds. The latter is the local government body that gets government grants and also launches self-sustaining ventures like jam production from produce grown in the village. “This way the village too has a responsibility,” says Madhukar. “They need to realise that nothing comes free.”

The programme includes improving the villages’ economy to make the schools self-sustainable. “The villagers, for instance, grow fruit trees and the foundation taught them to make jams and preserves out of their produce, which is then sold in cities,” says Madhukar. “Once the economic status improves, healthcare and education will take priority.”

The programme has also revolutionised the way children are taught, in that audio-visual learning has been introduced. “Over the past year my father, Rajendra Kumar Soni, a retired engineer who is now involved in philanthropy, donated computers along with basic educational software to several schools,” he says. “We saw that the kids were very keen to learn when audio-visual elements were included through computers.

“Organisations like Room to Read, the US-based charity, have partnered with us to provide a library for each school,” says Madhukar.

“I am also in talks with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Google Foundation and the Ford Foundation to pool manpower and technology to implement the best practices in education in these schools.”

Transfer of skills

Madhukar is looking for volunteers. “I already have a German who’s joining me soon to work on the project,” he says. “A couple of British teachers have offered to take time off to come and train teachers in Uttarakhand in activity-based learning and English.

“Anybody’s welcome to come stay with us, learn the model and implement it in their own region. The technology is easily available and can be replicated anywhere – whether in Afghanistan or Zimbabwe. It can be modified according to culture and region.”

After the implementation of the project in the two selected districts, Madhukar plans to move on to two other very remote districts – Pithoragarh and Champawat – that are higher up and harder to reach. If all goes well, in just a few years Asha Rani and hundreds of other children like her in the rural hinterlands of India will be able to study in schools manned by efficient, motivated teachers and learn with the aid of the latest audio-visual tools.

Tell us the story…

Do you know of an individual, a group of people, a company or an organisation that is striving to make this world a better place? Email us at friday@ gulfnews.com or the features editor at araj@gulfnews.com