Sana’a, Yemen: A drone-fired US missile struck a car southeast of here on a winter night last year, killing two alleged Al Qaida operatives who lived openly in their community.

But it also killed two cousins who were giving the men a ride and who the Yemeni government later said were innocents in the wrong place at the wrong time.

That incident, and other strikes that have followed, helped fuel anger here over civilian casualties from US drone attacks and what critics say is an even less scrutinised problem: the targeting of suspects who are within the reach of the law.

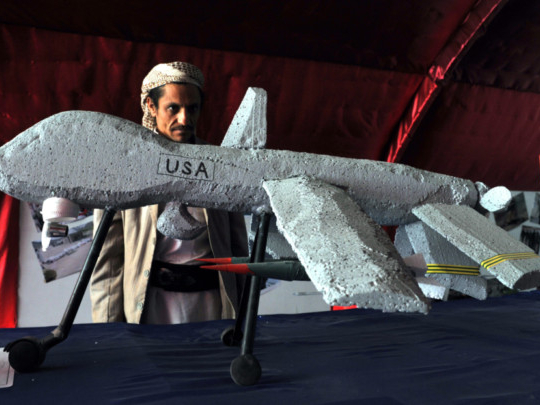

The US drone campaign in Yemen is aimed at rooting out Al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), which US officials have called the most active and deadly of the organisation’s wings. Drones have carried out at least 80 attacks since the start of 2011, according to the Long War Journal, which tracks US counterterrorism efforts.

As the strikes continue, public outrage is rising in Yemen, where many people, including government officials, argue that the attacks increase sympathy for Al Qaida. In December, after a drone attack killed more than a dozen people in a rural wedding convoy, Yemen’s parliament passed a non-binding motion to ban the strikes.

Drones are “a tool for killing outside of the law,” said Ali Ashal, a member of parliament who represents a district where US cruise missiles killed 41 people in 2009 but missed their alleged target, a high-ranking Al Qaida officer who Ashal said was “moving freely throughout the area and would pass by checkpoints”.

But the Yemeni government, riven by power struggles and corruption, relies on US funding for support and allows the attacks.

Yemeni politicians and experts say the government — which has struggled with domestic turmoil, weakened state institutions and deepening poverty since the 2011 uprising that ended President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s rule — appears less inclined than ever to set limits on US drones.

Yemen’s foreign minister, Abu Bakr Al Qirbi, told Reuters in September that drone strikes were a “necessary evil” in the country’s fight against terrorism and a “very limited affair”. At least four strikes have been carried out this year, according to local media.

The drone programme in Yemen, where most strikes take place in remote areas, is cloaked in secrecy. Members of the president’s office declined to be interviewed about it, as did Yemen’s National Security Agency and its defence and interior ministries. The Pentagon also declined to comment.

The Obama administration has defended armed drones as precise tools that limit civilian casualties and risk to US military personnel, and it has said it is investigating the attack on the wedding convoy.

Asked about that strike in December, a State Department spokeswoman told reporters that the US takes “every effort to minimise civilian casualties in counterterrorism operations”.

Amid an absence of transparency, there is wide speculation in Yemen that drones — and the intelligence from Yemen that at least partly informs targets selected by the CIA or Pentagon — are used as tools of politics and convenience.

Many politicians, activists and analysts think Yemeni security agencies prefer to identify suspects as eligible drone targets rather than arrest them — to avoid a messy legal process or a confrontation with a well-armed population in which tribal loyalties run deep.

What’s more, a shadowy battle for power and influence has gripped Yemen since Saleh ceded control to his deputy, Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi, in 2011. Saleh remains a powerful political force whose loyalists are said to crowd security agencies, and his rivals accuse him of manipulating intelligence on terrorist threats to eliminate enemies.

The murky political atmosphere has opened “the possibility that at different times, the United States is sort of being played — that different people give them intelligence and then ask the US to carry out a strike — and then it turns out that the US targeted a political rival,” said Gregory Johnsen, a Yemen expert and author of The Last Refuge: Yemen, Al Qaida, and America’s War in Arabia.

Congress has been troubled enough by seemingly poor targeting and civilian casualties — such as the Yemen wedding deaths — that it has sought to block President Barack Obama’s plan to shift control of the drone campaign from the CIA to the Pentagon.

The alleged targets of the US missile strike that killed Ali Saleh Al Qawili, a schoolteacher, and his cousin, Salim Hussain Ahmad, a university student, on January 23, 2013, were hardly fugitives.

Rabia Laheb, a local councilman and an active supporter of Al Qaida, and Naji Sa’ad, a powerful general’s bodyguard, were well-known members of Saleh’s tribe and hometown, 12 miles outside the capital, according to residents of their community. They passed regularly through checkpoints, and the road they travelled on the night they were killed was dotted with checkpoints, too, relatives of Qawili and residents said.

Why they were not detained is unclear. But they had turned against Saleh in Yemen’s 2011 popular uprising, and some in their community think that may have made them drone targets.

Residents said Laheb had held meetings for Al Qaida at his home. Two months before his death, a drone strike killed his close associate and suspected AQAP commander Adnan Al Qadhi. The watchdog organisation Human Rights Watch said Qadhi “could have been captured rather than killed”.

In a speech on US drone and counterterrorism policy in May, Obama said strikes are taken only when there is “near-certainty that no civilians will be killed or injured,” and he emphasised that the US prefers to capture rather than kill terrorism suspects. But legal and military experts say it is rarely so simple.

In countries such as Yemen, the US is unwilling to risk troops by sending in commando units, experts say. Critics of US drone operations have also accused the Obama administration of leaning on killing suspects since announcing plans to end detentions at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, because there is no obvious place to put captured ones.

Local authorities, on the other hand, may be too corrupt or incapable of doing the job themselves, experts say. In Yemen, repeated prison breaks have diminished confidence in security forces.

But another obstacle is diplomatic. States such as Yemen may allow the US to carry out air strikes but would generally prohibit boots on the ground, said Matthew Waxman, a law professor at Columbia University.

“If we could rely on those governments to do the capturing, we would, but these are generally situations where they can’t or they won’t,” Waxman said.

Critics say one result is civilian casualties. According to the Long War Journal, at least 116 people were killed in US air strikes in Yemen last year, about 15 per cent of them civilians. Other monitoring groups cite higher figures.

Two months after the air strike that killed Qawili and Ahmad, Yemen’s Interior Ministry apologised in a letter to their families, saying that the cousins were innocent and that it was “their fate” to die that night. The men who paid them for a ride, the government said, were members of Al Qaida.

The letter provided little solace to Qawili’s brother, Mohammad Ali Saleh Al Qawili, an Education Ministry bureaucrat. He formed a support group for drone victims’ families last year, and he said his quest for answers has proved illuminating.

“The bottom line is that they do not even go to the trouble of investigating, or seeing who is in a car, when [an intelligence] report is provided,” he said of the US government.

Qawili said he was astonished by how many other Yemenis he met whose kin had become targets or collateral damage when their vehicles were moving in the vicinity of Yemeni army and police checkpoints, where they might have been arrested.

“This is a useless war,” he said. “And every time they kill an innocent person, they motivate the families to join Al Qaida.”