Jeddah: When artist and calligrapher Nasser Al Salem decided that traditional Arabic calligraphy was too confining and sought break the bonds of the centuries-old art form, he was met with criticism and derision.

“I wanted to break out with a new art form,” the 32-year-old Makkah native told Gulf News. “Calligraphy needs to keep evolving to a different, unique style.”

The transition from traditional to contemporary calligraphy did not sit well with the old guard who view a modern take on what is considered a sacred expression of Arabic writing a violation of the standards of design. But Al Salem, who has been a calligrapher since he was 13 years old, is expressing a modern Saudi Arabia that is steeped in national, if not regional, pride.

Strict moral and cultural codes kept most art genres underground since 1979, a sharp reversal from the 1960s when the Saudi government encouraged art as a career by sending students abroad on scholarships to study and return home to teach.

But a majority of the next generation of Saudis eschewed the arts and humanities as frivolous and barriers to careers that generated a healthy income and prestige. Teaching and medicine reigned supreme while artistically-inclined children were discouraged to pursue their talent.

The culture changed dramatically for Saudis born after 1990 and who came of age in post-9/11 Saudi Arabia.

Satellite television and the internet exposed young people to Western and Asian media, particularly filmmaking, music and other forms of artistic expression.

The King Abdullah Scholarship Programme gave Saudi university students a full free ride to just about any accredited university in the world.

It allowed them to absorb and be comfortable with other cultures. No longer was a government job an answer to one’s future.

Many young Saudi artists today are self-taught while an increasing number are receiving formal training in foreign countries.

Maryam Bilal, who curates exhibits and serves as a liaison between the Athr Gallery of Jeddah and undiscovered artists, said the gallery looks for artists with a deep sense of regional identity.

“Their art has to be relative to what is happening today,” Bilal told Gulf News.

“Today we see displacement and home, and an identity to what is happening in the region. There is a longevity in their art.”

The government has brought 2.5 million displaced Syrians from their war-torn country into Saudi Arabia.

Their presence, influence and the tragedy of their experiences and losses are deeply felt among Saudi artists who express the emotional toll of war and its impact on the region less in political terms and more of its humanity.

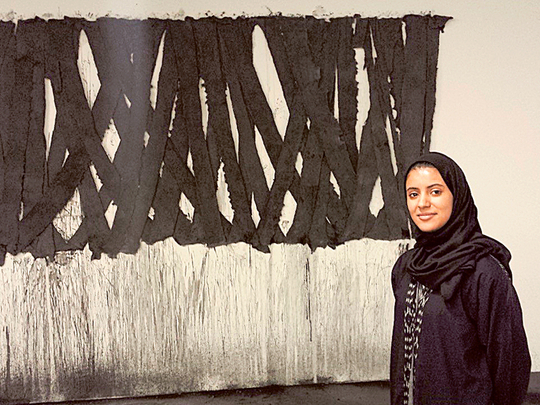

Afia H. Bin Taleb, 26, who trained as an interior designer and is a project associate with Athr Gallery, said Zarah Al Ghamdi, who often creates site-specific installations, is one artist who depicts the human relationship to the environment in a visceral manner by using black paint to allude to the scorched, scarred and polluted earth, not unlike the destruction witnessed in the region.

“A lot of the art we see today is conceptual,” Bin Taleb said.

Such themes have attracted museums and galleries from the Smithsonian and the Armory Show in New York to Art Dubai to showcase Saudi artists.

International exhibits can be a heady experience for a young Saudi attempting to make a name in art circles.

Yet recognition, particularly in Saudi Arabia, remains elusive. The number of artists, whose work has matured, is increasing significantly, but the environment to support such artists has failed to mature with them.

Jeddah artist Fatima Baazeem said artists were “not highly appreciated” in the past.

While the arts community is blossoming, she said, recognition is difficult to come by, giving some artists the feeling they are being marginalized in the community where they work.

Baazeem noted that a group of artists recently staged a protest to draw attention to their art. Each artist cut up one of their works and donated it to create a collage as a single expressive theme. It was a collective statement that their work had value. “I wasn’t entirely satisfied with the final result, but it certainly sent a message.”

Al Salem agreed that artists struggle to be seen and heard.

“There is not enough exposure,” Al Salem said.

“There is not enough media. We can’t find good critiques. We can’t find serious art critics.”

Bilal said there is a lack of infrastructure to support local talent.

“There is not enough platforms for artists,” she said. “There are not enough museums and galleries. We don’t have a collecting culture here. I understand the frustration of artists. We are very slow in developing a collecting culture.”

The Saudi art scene appears to be in a state of limbo. Artists are eager to see whether Saudis with the financial means will evolve into art patrons and benefactors to help establish galleries and museums to bring art to the public. It hasn’t happened on a scale that will draw enough attention both domestically or internationally, but there is an expectation among artists that it’s only a matter of time.

There is also an anticipation of “what’s next” in Saudi society, Bilal said.

“I think the public is ready,” she said. “We see it in social media, photography, YouTube and other media outlets. They are ready for galleries, for museums and for cinemas.”