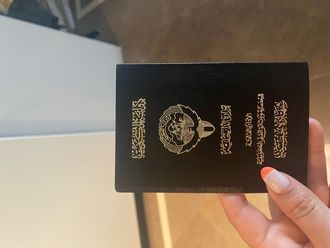

Manama: In a reversal of social trends in Qatar, Western dress has become "taboo" while national clothing like the thobe and the ghitra have become status symbols, a scholar has said.

"Struck by the stark contrast between the desert and the post-modern steel-and-glass skyscrapers lining the Doha Bay, I have begun to research cultural expressions of the tribal modern in Qatar," Miriam Cooke, Professor of Arab Cultures at Duke University and Fall 2010 Scholar-in-Residence at the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, said.

"This is a reversal of previous trends," she said in a lecture on popular and official efforts to incorporate a "modern" tribal heritage into daily life in Qatar and the Gulf region, Qatari daily Gulf Times reported.

The event was hosted by Georgetown University School of Foreign Service in Qatar (SFS-Q) as part of its monthly dialogue series sponsored by Georgetown’s Center for International and Regional Studies (CIRS), a spokesperson said.

During her presentation, "The Tribal Modern: The Past as Future", Cooke examined the various ways in which the Gulf tribal is being expressed in Qatar, particularly in local architectural projects, popular dress and Nabati poetry competitions.

The architectural revival of Souq Waqif is an example of the growing "heritage industry" across the Gulf region, and the resurging popularity of Bedouin poetry, Nabati is a case of tribal modern expression, she said.

Cooke who holds a PhD in Arabic literature has based her remarks on research she conducted across the Arab world and the Gulf region.

According to Suzi Mirgani, CIRS Publications Coordinator, Cooke acknowledged in examining a variety of "heritage projects" in Qatar and the Gulf states, the literature of Ibn Khaldun and his binary scheme of distinction between the desert nomadic, otherwise known as "badawa," and the sedentary urban, known as "hadara" in many current Arab cultures.

The "badawa" symbolises nomadism, loyalty, and tribalism and "hadara," on the other hand, is symbolic of modernity, urbanisation, and individualism. Both concepts are used to distinguish the "self" from the "other" in Arab societies.

When used to describe the self, Cooke argued, either word has positive connotations, but when used to describe the other, it is often tinged with criticism of the other’s way of life, be it modern or traditional. "These two terms are current in Gulf vocabulary, and are deployed to designate cultural differences," she said.

Cooke said that both concepts are constitutive of the heterogeneity inherent in Arab cultures and so it is important "to bring the two cultures together in such a way that they complement and enhance each other and strengthen the modernisation efforts underway" in many Gulf states.

These largely oppositional tropes between the traditional and the modern are negotiated and played out in the current "heritage projects", she said.

Areas such as Suq Waqif in Doha are primary examples of how the old and modern aspects of Qatari culture are intertwined in architectural design of public spaces.

Suq Waqif differs greatly from the highly modernized cityscape of the downtown financial district of West Bay, and, so, according to Cooke, the architecture of Doha has become an assimilation of the old and new and of the "badawa" and "hadara."

"Where the skyscrapers compete for the prize in cutting-edge Western technology and aesthetics, and the Museum of Islamic Art was designed to blend the architectural variety of Islamdom into a single seamless whole, Suq Waqif was to be made of local materials and to embody the spirit of the Gulf," she said. "Indeed, Suq Waqif, for me, is the emblematic working out of the tribal modern."

In her arguments, Cooke said that the historical reference to cultural and tribal purity, or asala, is a symptom of globalisation and modernity as nations attempt to rebuild cultural identities after years of colonial struggle.

"The Arab world states, whose citizens are the first generation to grow up with a national, rather than a regional, identity, are involved in a future articulation of a largely unrecorded past that lies buried under the surface of identical newly global cities," she said. In this sense, many of these renovation projects are state-sponsored and are in service to the idea of the patriotic.

Cooke said that "heritage projects erase pre-national ethnoscapes and deterritorialise lifestyles."

"They provide the tabula rasa on which the mass migrations of workers can be projected as new. Colonialism disappears behind the façade of ethnic purity and isolation. The heritage that is being revived glosses over four centuries of struggle between the Portuguese, the Ottomans, and the British for control of the valuable waterways that link the Fertile Crescent with the Indian Ocean," she said.

In her conclusion, she said that in any of these heritage projects, whether architectural, sartorial, or linguistic, it is not an actual tribe that is being revived to serve as the backdrop for the embodiment of cultural purity, but the "idea" of a tribe.

"It does not matter that Suq Waqif is a simulacrum; it produces the ideal, the idea, and the feel of the authentic (the aseel)," she said.