The 1991 Gulf War saw only 100 hours of ground fighting as US forces entered Kuwait to end the Iraqi occupation, but echoes of that conflict have lingered for decades in the Middle East.

The war pushed America into opening military bases in the Gulf and Saudi Arabia, drawing the anger of an upstart militant named Osama Bin Laden and laying the groundwork for Al Qaida attacks leading up to September 11, 2001. Saddam Hussain, demonised as being worse than Adolf Hitler by president George H.W. Bush, would outlast his American rival in power until Bush’s son launched the 2003 American-led invasion that toppled the Iraqi dictator.

Now, 25 years after the first US Marines swept across the border into Kuwait, American forces are battling the extremist Daesh, born out of Al Qaida, in the splintered territories of Iraq and Syria. The Arab allies that joined the 1991 coalition are fighting their own conflicts at home and abroad, as Iran vies for greater regional power following a nuclear deal with world powers.

Iraq itself is now fragmented and war-torn to a degree few could have imagined after that 1991 US victory. The Daesh terrorists have imposed their rule over many of the Sunni-dominated areas of the country, Kurds in the north have their own virtual mini-state and Shiites — many of them allied to Iran — lead the government in Baghdad.

In all, the United States finds itself in the quandary it hoped to avoid back in 1991.

“Had we taken all of Iraq, we would have been like the dinosaur in the tar pit — we would still be there, and we, not the United Nations, would be bearing the costs for that occupation,” the late US Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf, commander of Desert Storm, wrote in his memoirs.

Iraq invaded Kuwait on August 2, 1990, angry that the tiny neighbour and Gulf states had ignored Opec quotas, which Saddam claimed cost his nation $14 billion. Saddam also accused Kuwait of stealing $2.4 billion by pumping crude from a disputed oil field and demanded that Kuwait write off an estimated $15 billion of debt that Iraq had accumulated during its 1980s war with Iran.

Fearing Saudi Arabia could be invaded next, US officials moved quickly to deploy troops to the region. After months of negotiations and warnings, the US launched its assault on Iraqi forces in Kuwait on February 24, 1991.

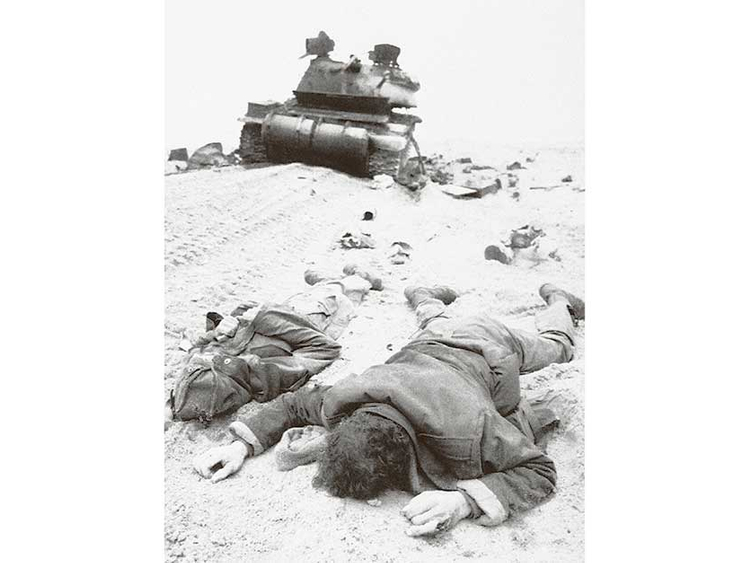

In purely military and political terms, the first Gulf War marked a tremendous success for the US, which was still haunted by Vietnam. America suffered 148 combat deaths during the entire conflict, while 467 troops were wounded out of more than 500,000 deployed, according to the US Defence Department. The US held together an allied army, its war effort was supported by a number of United Nations resolutions, and the conflict cemented its position as the sole world power following the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

America’s Arab allies also footed much of the bill for the $61 billion war, with both Saudi Arabia and Kuwait contributing some $16 billion, while the United Arab Emirates offered $4 billion, according to US congressional reports. Japan and Germany together contributed another $16 billion, while South Korea gave $251 million. The US covered the rest.

The key players in the Arab world at the time of the conflict are now long gone.

Saudi King Fahd died in 2005. A popular uprising toppled Egyptian autocrat Hosni Mubarak in 2011. Syria’s totalitarian ruler Hafez Al Assad, a longtime US foe who joined the Gulf War effort to reap billions in aid and diplomatic benefits, died in 2000. His son, President Bashar Al Assad, still clings to power amid a five-year civil war that has killed more than 260,000 people and flooded Europe with tens of thousands fleeing violence across the region.

In Israel, the memory of Iraqi Scud missile-fire prompted the military to speed up a missile-defence program that included the development of its Iron Dome rocket-defence system with the help of the Americans. Then-prime minister Yitzhak Shamir, a hard-liner, held back from retaliating at the request of Bush, who feared losing Arab support for the war. Though American aid to Israel exceeds $3 billion a year, relations have been strained over stalled Palestinian peace talks.

Yet despite seeing his forces routed from Kuwait, Saddam clung to power and survived an uprising by both Shiites and Kurds following the war. The US and its allies began to patrol a northern and southern no-fly zone to protect the Shiites and the Kurds while Saddam remained a thorn in the side of American politics for more than a decade.

“I miscalculated,” Bush said in a December 1995 interview. “I thought he’d be gone.”

It would take president George W. Bush’s 2003 invasion to end Saddam’s reign, coming amid the US campaign in Afghanistan. In its aftermath, Al Qaida in Iraq would arise and be put down by a US military surge, coupled with the support of Sunni tribesmen. But as the US withdrew from Iraq and Baghdad stopped supporting the Sunni tribesmen, Daesh emerged from the ashes of Al Qaida in Iraq and in 2014, took control of about a third of both Iraq and neighbouring Syria.

Today, the US finds itself mired in a long war feared by Schwarzkopf and others who oversaw Operation Desert Storm. Oil prices, which sparked Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait, have dropped to under $30 a barrel from more than $100 in just a year and a half.

The cause, in part, is the same Opec overproduction the late dictator Saddam railed against across the splintered Middle East.